Daniel Comboni

Missionnaires Comboniens

Zone institutionnelle

D’autres liens

Newsletter

Tuesday, March 10, 2026

The Comboni Missionaries in Poland recently invited their confrere Father David Glenday to share his reflections on Pope Leo’s letter Dilexi Te regarding love for the poor. The texts which follow – a general introduction and a brief personal response to each of the letter's five chapters – is the result. Fr David has been a priest for almost fifty years and served in Uganda and the Philippines. He was superior general of the Comboni Missionaries from 1991 to 1997.

Mission – a matter of love

A good question

I was fortunate enough, during my life as a Comboni Missionary, to spend eleven years serving in the Philippines. I remember one day there that a committed young layman fired this question at me: “Father David, you Combonis often speak with enthusiasm about your vocation and your Founder, St Daniel Comboni. You share about his dreams, his drive, his journeys, his hopes and disappointments, his heritage and memory – and that is all very beautiful and inspiring. But now what I would like to know is this: what is the heart, the centre, the engine of St Daniel’s mission, and of your mission today?”

A very good question indeed, and one which during my almost fifty years now as a missionary I have often tried to answer, searching for the right words, and even more for the right deeds. If my young friend were to ask me the same question today I would not hesitate to enlist the help of not one, but two Popes: Francis and Leo. In fact, it is really striking that Pope Francis’ last major letter entitled Dilexit Nos was about love – “the human and divine love of the Heart of Jesus Christ”, and Pope Leo’s first letter to the whole Church Dilexi Te is about… love – “love for the poor”. It is clear then: as Pope Francis says, “mission becomes a matter of love”, and missionaries are people who are “in love and who, enthralled by Christ, feel bound to share this love that has changed their lives”.

Mission as love: yes, this is the stupendous and splendid reality that forms a bridge holding the Popes’ two letters together, and that also gives us the key to begin reading, praying and living Dilexi te – as we hope to do over the coming year. And we want to do this not so much as to collect some interesting ideas, but in order rather to grow as missionaries, each of us in his or her own special circumstances.

So what deep discoveries about mission can we hope to make on this journey, with Pope Leo’s letter as our roadmap?

First, our God is a missionary God

Mission is a matter of love, and in the end this is because mission is born of God, the Trinity of love. Everything Jesus says and does in the Gospels, by the power of the Spirit, makes this plain: our God is not distant, aloof, indifferent, uninvolved. No, our God is on the move, outgoing, committed, interested, close, passionate.

And we are baptized in the name of this missionary God. By our baptism the Three take up residence in our deepest hearts and set about forming us into missionaries – like them!

This theme, this reality of the missionary Trinity, was very powerfully present in the teaching and witness of Pope Francis (think, for example, of his first letter Evangelii Gaudium) and has been taken up with energy by Pope Leo. Both of them urge the Church to be where the Three already are: at the edges, on the peripheries, with those who are deemed far away. In Dilexit Nos Pope Francis insists that our hearts are to be transformed into the Heart of Jesus, a heart that goes out to the wounded and weak, and Pope Leo deepens and consolidates this missionary call.

So mission is a matter of love, because God is love, and God’s love is a missionary, outgoing love.

Second, encountering God in mission

So the Trinity of Love impels us to mission – but also awaits us there. During my years in the Philippines – I ministered in a tiny corner of the mega-city of Manila – I had the grace of learning the national language, Tagalog, and of thus being able to accompany especially one small community in the city’s slums.

With them I made the moving discovery which is the treasure of so many missionaries’ lives: that the God who is love precedes us in our missionary journey, and that we come to know this God afresh in the lives and especially the hearts of the poor to whom we are sent. In the example of their lives mission becomes a matter of learning love, where love has the face of solidarity, of gratitude, of courage, of joy, of endurance, of good sense, of tolerance.

In mission with and to the poor, we missionaries learn to love.

Third, working with God in mission

Because mission is a matter of love it is also a matter of deeds, of work, of action. As Jesus says in John 5, 17, “my Father is always at work until today, and I too am working”, and he fills this out in John 15, offering us the rich portrait of the Father as the vinedresser. The Father is delighted by our abundant fruits, Jesus tells us, and St John underlines the same vision when he encourages us to love in practice and not in theory.

Because of love, we are God’s coworkers, as St Paul insists, and this is both a joy and a challenge. It is a great joy to know that the Lord wants us to join him in loving the poor, that he desires our company and solidarity: it is a new way to appreciate our great dignity and potential in the grace of baptism. And it is also a challenge, because it means that we need first to discern how God is loving the poor here and now, so that we can respond to this divine initiative. God loves the poor first.

Finally, transformed by love

When we understand and live mission as love in these different ways, something wonderful and powerful happens: we are changed, transformed. We come to realize little by little that what really matters in our service of the poor is above all who we are, and we discover that we are becoming a sign, a sacrament of God’s loving presence.

Yes, we are transformed but also by God’s grace so are those to whom we are sent, as they are led to a new awareness of their infinite value and dignity, and of their potential as human beings, sons and daughters of the Father who loves them in a very special way.

As we look forward to praying and studying Dilexi Te over the coming year, we do well to dwell on Pope Leo’s concluding words:

Christian love breaks down every barrier, brings close those who were distant, unites strangers, and reconciles enemies. It spans chasms that are humanly impossible to bridge, and it penetrates to the most hidden crevices of society. By its very nature, Christian love is prophetic: it works miracles and knows no limits. It makes what was apparently impossible happen. Love is above all a way of looking at life and a way of living it. A Church that sets no limits to love, that knows no enemies to fight but only men and women to love, is the Church that the world needs today.

* The numbers in brackets refer to the paragraph of the letter from which the quotation is taken.

1. When I listen, it is then I see

Words that make a difference

I still have this Bible with me, fifty years after I offered it as a gift to my parents on the day I was ordained a deacon. At the time, I imagined that at most it would be given a place of honour on the family bookshelf, but what in fact happened was very much better than that.

In the ensuing months and years, as I visited my family home, I discovered that the Bible has found its place by my father’s favourite armchair. I never saw him actually reading it, but when he was not around I made it my business to examine it, and found all the signs that this book was indeed being regularly read, no doubt in the mornings when Dad rose early for his porridge and coffee, and was alone and unobserved.

Dad was not a Catholic: he was a Scot and a Presbyterian, and by the time of this story had been happily married to my Irish Catholic mother for over thirty years. Then, one quiet Sunday evening, he surprised us all by simply declaring: “I have decided to become a Catholic”. And thus it was that one month before leaving for my first mission assignment in Uganda, I had the joy of concelebrating at the Mass of my 71-year-old father’s First Holy Communion.

I do not doubt that the grace of those quiet early mornings, alone with God’s Word, was one important key to Dad’s unexpected and courageous step, opening our family to a deep new communion and a grateful joy.

That Bible, those words, that Word, had made a difference. Listening had led to seeing., or as Jesus said: “As I hear, I judge” (Jn 10,30).

You want to see? Then listen!

“A few essential words”: the title Pope Leo has given to the first chapter of his “Dilexi Te” points us firmly in this same direction. There is an uncompromising insistence that if the Church, if we that is, really want to see and so to love the poor, then this will begin with an attentive listening.

The Pope leads us back to the burning bush where God tells Moses: “I have observed the misery of my people… and I have heard their cry”, and God leaves Moses in no doubt that this is the path which he too is called to tread, if he wants “to enter into the heart of God” and so to accomplish the daunting mission entrusted to him.

Towards the end of the chapter Pope Leo challenges us in the same sense, calling for a re-reading of the Gospel, so as to reconnect with that love for the poor which, he says, is “the burning heart” (15) of the Church’s mission. He underlines the point by recalling the experience of Saint Francis of Assisi, converted by direct contact with the poor and outcast of society (7).

Seeing with fresh eyes

As we have noticed as we began this simple reflection, when we listen to the Word, new things can happen. Recalling Saint Paul VI’s homily at the end of Vatican II, Pope Leo expresses this conviction: that listening to the cry of the poor, and encountering the Lord in them, both Church and society will open themselves to new energies and possibilities, to “an extraordinary renewal” (7).

Yet the Pope makes it very clear that this is no painless, easy formula: seeing in this new way involves deep purification, “a change in mentality” (11), and particularly the readiness to see how things really are, and how they really are for everyone.

Statistics certainly have their place, but there will be times when they do not do justice to the daily lives of real people – and it is to their cry that we are called to respond. Again, seeing poverty today will mean taking in the fact that “in general, we are witnessing an increase in different kinds of poverty, which is no longer a single, uniform reality but now involves multiple forms of economic and social impoverishment, reflecting the spread of inequality even in largely affluent contexts” (12). In this context Pope Leo particularly calls for a new sensitivity and response to the poverty of women “since they are frequently less able to defend their rights” (12).

Yes, listening and seeing demand purification and healing of the “blindness and cruelty” (14) which blame the poor for their own situation, and this even on the part of some Christians “who have succumbed to attitudes shaped by secular ideologies or political and economic approaches that lead to gross generalizations and mistaken conclusions”(15).

Listening to the Lord

My Dad – listening quietly, humbly, even hiddenly – discovered Jesus in a new and life-giving way and took a courageous step forward. Highlighting the same dynamic link between listening and seeing, Pope Leo is convinced that if today the Church truly listens to the poor, this will mean a new encounter and a new discovery of her Lord:

Love for the Lord, then, is one with love for the poor. The same Jesus who tells us, “The poor you will always have with you” (Mt 26:11), also promises the disciples: “I am with you always” (Mt 28:20). We likewise think of his saying: “Just as you did it to one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did it to me” (Mt 25:40). This is not a matter of mere human kindness but a revelation: contact with those who are lowly and powerless is a fundamental way of encountering the Lord of history. In the poor, he continues to speak to us (5).

For prayer, reflection and sharing:

In my life have there been “a few essential words” that have inspired me in my love for the poor?

2. A journey of the heart

Khartoum, Sudan, October 10, 1996: along with thousands of exultant Sudanese Christians I was blessed enough to find myself part of a great, colourful and deeply emotional celebration of the Eucharist. Under a bright blue sky, and in no little heat and humidity, we were celebrating for the first time on his feast day proper the holiness of missionary Bishop Daniel Comboni, father of the Church in the Sudan, who had been beatified in Rome by Pope Saint John Paul II a few months earlier. The atmosphere was, to say the least, electric.

It fell to me, as the then superior general of the Comboni Missionaries, to hold aloft and carry in procession to the Archbishop of Khartoum, Gabriel Zubeir, the relic of Comboni. As I did so, I could read the words painted brightly on the altar backdrop: “Welcome back, Comboni, to where your heart is”. Words both touching and apt, for Daniel Comboni’s life of dedication to mission, and so of choosing the poor, had indeed been a long and arduous journey, and this day of celebration was a special homecoming for this man who had so heroically journeyed at his Master’s bidding.

Yes, as Pope Leo affirms in Dilexi Te, God does choose the poor, and the lives of women and men like St Daniel Comboni illustrate how our becoming involved in God’s choice sends us off too on our own personal journey and adventure, with the Three Persons of the Trinity as our pilgrimage companions.

When the heart decides to journey

Where, though, does this journey of love for the poor begin? About this, Pope Leo is keen to leave us in no doubt: three times in as many pages he speaks movingly of God’s heart “full of love” (16), “which has a special place…for those who are discriminated against and oppressed” (16, 17). Just a little earlier in his letter he had written: “In hearing the cry of the poor, we are asked to enter into the heart of God… If we remain unresponsive to that cry… we would turn away from the very heart of God” (8).

And this movement of God’s own heart generates a journey which is a choice: God’s “descent and coming among us” (16) draws the Trinity to the poorest and the weakest, in a decision which has come to be known as God’s preferential option for the poor, his special care for those for whom nobody cares.

The consequence of all this for those who are children of this journeying God is plain to see: “God asks us, his Church, to make a decisive and radical choice in favour of the weakest” (16). Indeed, Pope Leo candidly expresses a sense of surprise: “I often wonder, even though the teaching of Sacred Scripture is so clear about the poor, why many people think that they can safely disregard the poor” (23).

The journey Jesus travelled

Jesus is God-with-us, this we know, but perhaps what the Pope has been saying invites us to add an important emphasis: Jesus is the presence with us of the God who chooses the poor. And this becomes very clear when we consider the poverty of Jesus, “the poor Messiah” as Pope Leo calls him.

Jesus lives poorly at many levels: he is born into a family of very modest means and learns to earn his living by the work of his hands; he experiences various forms of exclusion from the very first day of his life on this earth; in his active ministry he depends on the hospitality and support of his friends and followers; he knows what it means to be tired and sad and anxious; he has to live with rejection and suspicion. He dies on a cross outside the city walls amidst the mockery and derision of those gathered to watch the spectacle, abandoned by almost all of his disciples.

Yet this is not the whole story of Jesus’ journey with the poor; the matter goes very much deeper. Responding with limitless generosity to his Father’s invitation of love and mercy towards wayward humankind, Jesus divests himself of his splendor and heavenly glory and takes on the form of a servant. The deep significance of all this is well conveyed by Jesus’ own words: “Very truly, I tell you, the Son can do nothing on his own, but only what he sees the Father doing; for whatever the Father does, the Son does likewise” (Jn 5, 19). Jesus learned to love the poor and to be poor from the Father.

Journeying with Jesus

For those of us who want to make this journey with Jesus, what will be our roadmap? Pope Leo has some suggestions to offer: first, he says, take in your hands the Scriptures, and especially those that record the life and practice of the first Christian communities; then pay careful attention to how these brothers and sisters in the faith joined the Risen Jesus on his journey to the poorest; welcome all this “as an example to imitate, but also as a witness to the faith that works through charity and as an enduring inspiration” (34).

At this point of his reflection Pope Leo is strongly reminded of Pope Francis and of what Pope Francis wrote in his still highly significant letter Evangelii Gaudium: God’s word is “so clear and direct, so simple and eloquent, that no ecclesial interpretation has the right to relativize it… Why complicate something so simple?” (31).

It was this simple, but powerful, Good News that the Christians of the Sudan were celebrating on that distant October afternoon, the Good News made flesh in the life and mission of one remarkable man, their father in the faith. By God’s grace, he had chosen the poor, and so had discovered the path to lasting joy: will we, too, make this choice and journey to that joy?

3. Meeting God

Mrs Kikilai’s cross: touching the suffering flesh of Jesus (49)

During the stage of my missionary formation known as the novitiate I was keen to spend time finding out what it felt like to earn a living by manual work, and my superiors encouraged me and my companions in this. It was thus that I found myself working as a labourer on a building site in the English Midlands. Of course, my companion and I needed to find ourselves a place to stay, and we were fortunate enough to rent a room with a Hungarian lady who went by the memorable name of Mrs Kikilai. She was one of the hundreds of thousands of Hungarians forced to flee their country when Soviet tanks invaded their nation and imposed an oppressive regime in the mid-1950s.

Mrs Kikilai was a splendid and generous cook – our evening meals prepared by her were always a high point of our day – but for the rest she was very quiet and discreet. When the day came for us to return to the novitiate, however, she sprang a beautiful surprise on me, handing me quietly a small brass crucifix, brought by her no doubt from her home in Hungary: its features had been worn away by who knows how many generations, we may suppose, of her family and friends.

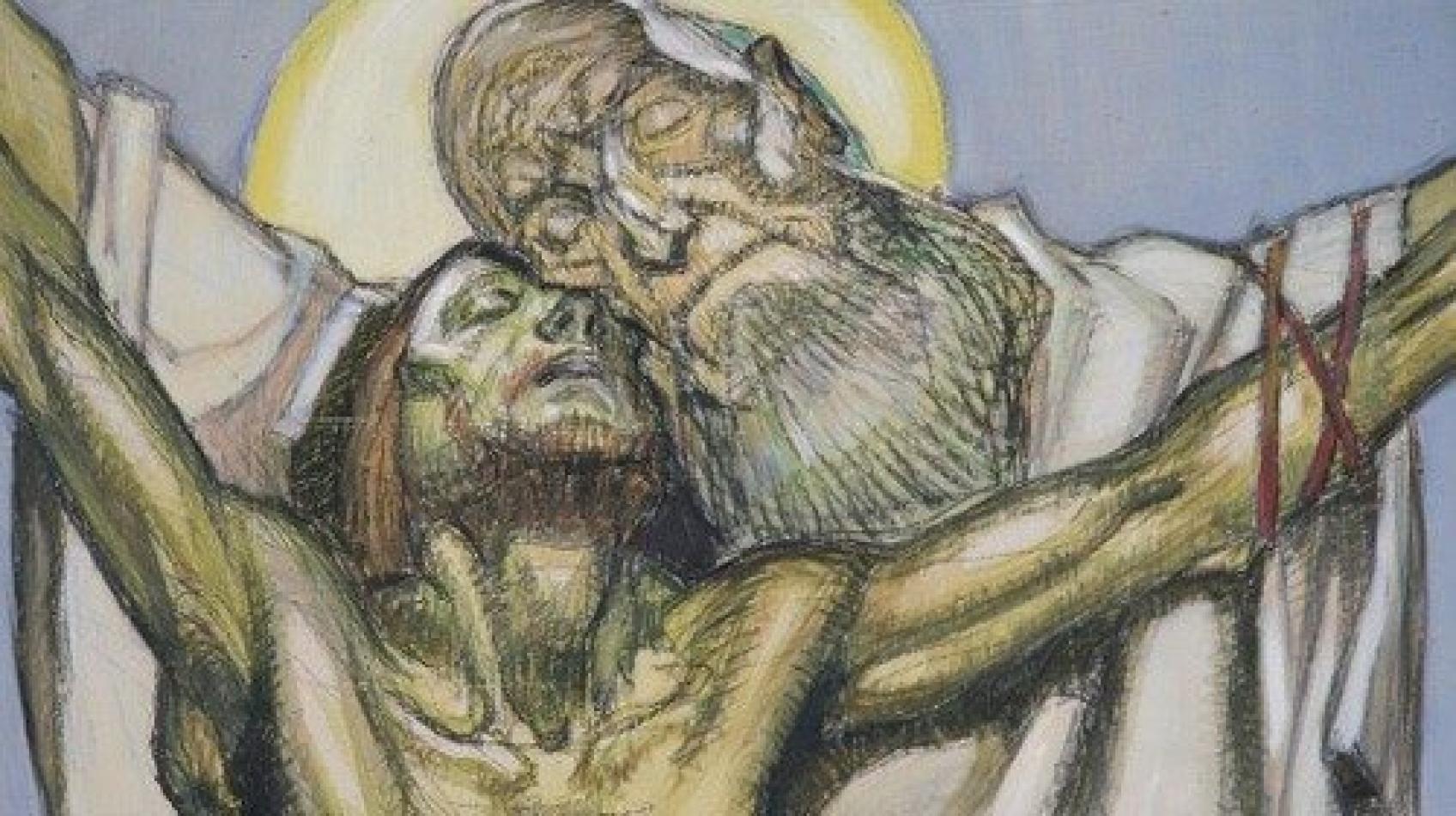

This little crucifix, which I still have with me and which came with me to my missions in Uganda and the Philippines, speaks of so many men, women and children reaching out to touch the flesh of the Crucified Jesus, hope and solace of the poor down the years. “Touching the suffering flesh of Jesus”: this is an image of the Church’s love for the poor that recurs several times in Dilexi Te:

For Christians, the poor are not a sociological category, but the very “flesh” of Christ. It is not enough to profess the doctrine of God’s Incarnation in general terms. To enter truly into this great mystery, we need to understand clearly that the Lord took on a flesh that hungers and thirsts, and experiences infirmity and imprisonment. A poor Church for the poor begins by reaching out to the flesh of Christ. If we reach out to the flesh of Christ, we begin to understand something, to understand what this poverty, the Lord’s poverty, actually is; and this is far from easy (110).

Roast chicken in the night: when the poor live the Gospel (102)

At the end of January 1986 Yoweri Museveni took power in Uganda (East Africa), where at the time I was serving as a missionary, and ushered in a period of renewed civil and military conflict. Together with five of my confreres, I found myself embroiled in this situation, having for safety to abandon our mission and seek refuge with friendly people living deeper in the bush and further from the main road.

One night, as things became more dangerous, we made our way further into the less inhabited farmlands and eventually decided to stop to rest with a family of farm workers who offered us this hospitality. The following morning, as dawn broke, we had already started to move off, when the lady of the house came after us calling and entrusting a package to one of our group.

The day that followed proved to be providential and we eventually found ourselves in safe hands… and then remembered we were hungry! The lady’s packet was opened to reveal a roast chicken, which she had spent the night preparing for us:

Only the closeness that makes us friends enables us to appreciate deeply the values of the poor today, their legitimate desires, and their own manner of living the faith… Day by day, the poor become agents of evangelization and of comprehensive human promotion: they educate their children in the faith, engage in ongoing solidarity among relatives and neighbors, constantly seek God, and give life to the Church’s pilgrimage. In the light of the Gospel, we recognize their immense dignity and their sacred worth in the eyes of Christ, who was poor like them and excluded among them (100).

“My best friend”: an encounter between equals (79)

I had just finished celebrating a “street Mass” in one of the most deprived slums of Quezon City in the Philippines and was surrounded as usual and as is the custom with vivacious children wanting an individual blessing when I felt an insistent tapping on my stomach. There stood little “JP” (short for John Paul!), who for some time had declared to all who cared to hear that he was Father David’s best friend.

“Yes, JP, what is it?”

“Father David, masaya po kami dahil nandidito po kayo. We are happy because you are here”.

I thought to myself: JP, you may be small, but in your way you are a great theologian; you have understood the point of the Church, the point of mission. The Church’s mission is about “being here”, about a presence that brings joy and creates community. You have articulated for me the sense of my missionary vocation: thank you! As Pope Leo says,

the poorest are not only objects of our compassion, but teachers of the Gospel. It is not a question of “bringing” God to them, but of encountering him among them. Serving the poor is not a gesture to be made “from above,” but an encounter between equals, where Christ is revealed and adored (79).

4. Making change happen

Healing the deepest roots (91)

In the early part of Chapter Four Pope Leo describes in broad strokes how the Church’s social teaching grew and developed throughout the twentieth century and, with Popes Benedict and Francis, into the twenty-first. As a former missionary in Peru, the Pope gives deserved attention to how the Latin American bishops grasped this universal teaching with enthusiasm and commitment, applying it to their particular context, and thereby deepening and enriching it for the worldwide Church. “I am greatly indebted,” he writes, “to this process of ecclesial discernment, which Pope Francis wisely linked to that of other particular Churches, especially those in the global South. I would now like to take up two specific themes of this episcopal teaching” (89).

The first of these specific themes is that known as “structures of sin”. What is meant here? It is evident that injustice can be done, and is in fact done, to the poor through individual acts and decisions on the part of persons and groups, and that the Gospel calls us to redress these acts and decisions in repentance and genuine love. More recent thinking, however, goes further by identifying attitudes, ideologies, prejudices, and theories that can often be the “deepest roots” of the unjust and unloving actions and decisions that grow from them. These deeper roots are the structures of sin Pope Leo is naming and denouncing.

There is, for example, the “dictatorship of an economy that kills” (92); there are “ideologies that defend the absolute autonomy of the marketplace and financial speculation”(92); there is “a dominant mindset that considers normal or reasonable what is merely selfishness and indifference” (93). These attitudes, says the Pope, lead to considering the reality of the poor as inevitable or even their own fault, or at any rate only to be denounced and challenged at some indefinite future date. The poor are not known and seen as brothers and sisters but as a theoretical problem somehow to be solved.

The Gospel, instead, calls for something quite different. Pope Leo writes:

All the members of the People of God have a duty to make their voices heard, albeit in different ways, in order to point out and denounce such structural issues, even at the cost of appearing foolish or naïve. Unjust structures need to be recognized and eradicated by the force of good, by changing mindsets but also, with the help of science and technology, by developing effective policies for societal change (97).

Reality best viewed from the sidelines (82)

If the charity that changes reality calls for the depth of vision and analysis of which Pope Leo has been speaking so far, he is equally convinced that the agents of this change can and must in the first place be the poor themselves, that, in other words, there is a “need to consider marginalized communities as subjects capable of creating their own culture, rather than as objects of charity on the part of others” (100). The reason is evident: “Their experience of poverty gives them the ability to recognize aspects of reality that others cannot see… Society needs to listen to them” (100).

The Pope provides us with a rich and moving vocabulary to draw out the sense of this particular listening: “the closeness that makes us friends” with the poor, “we recognize their immense dignity and sacred worth in the eyes of Christ”, “we will share with them the defense of their rights”, in “loving attentiveness”. Quoting Pope Francis, Pope Leo affirms:

True love is always contemplative, and permits us to serve the other not out of necessity or vanity, but rather because he or she is beautiful above and beyond mere appearances… Only on the basis of this real and sincere closeness can we properly accompany the poor on their path of liberation (101).

Those who have worked with and, especially, among the poor will gratefully recognize themselves in this call totrue, contemplative love, as well as in the moving portrait offered of their excluded brothers and sisters by Pope Leo at the end of this penultimate chapter of his letter:

Growing up in precarious circumstances, learning to survive in the most adverse conditions, trusting in God with the assurance that no one else takes them seriously, and helping one another in the darkest moments, the poor have learned many things that they keep hidden in their hearts.

This “mysterious wisdom” is a gift for “those of us who have not had similar experiences of living this way... Only by relating our complaints to their sufferings and privations can we experience a reproof that can challenge us to simplify our lives” (103).

For prayer and reflection

Pope Leo writes: The martyrdom of Saint Oscar Romero, the Archbishop of San Salvador, was a powerful witness and an inspiration for the Church. He had made his own the plight of the vast majority of his flock and made them the center of his pastoral vision (89).

Saint Oscar struggled courageously to dismantle the structures of sin and he did this in communion with the poor. How does he inspire us to carry forward the same struggle and to draw close to our excluded brothers and sisters?

5. The love that knows no limits

Needless to say, the whole Comboni family was delighted to discover their Founder mentioned twice, even if somewhat indirectly, in Pope Francis’ letter Dilexit Nos: yes, the divine and human love of Jesus for all humankind and for every single human being was indeed the centre and source of Daniel Comboni’s remarkable and heroic missionary life.

But what of Pope Leo’s Dilexi Te on love for the poor? Do we find something significant of our founder there? It seems to me that the answer is a resounding and challenging yes – both throughout the Pope’s reflection, and perhaps especially in the powerful final chapter, anyone with ears to hear can pick up the echo of not a few of Comboni’s key insights, placing him within what the Pope calls “the Church’s great Tradition” (103) on care for the poor.

Seeing the poor

Again and again in his letter Pope Leo denounces how easy it can be, even for followers of Jesus, simply not to see the poor, not to notice their existence. In his last chapter he once again draws attention to “a serious flaw present in the life of our societies, but also in our Christian communities. The many forms of indifference we see all around us…” (107).

Comboni, too, would speak of his vocation as a special gift of being able to see the real world and the world’s poor, and to see them in a new way. This, for example, is how he speaks of his prayer at St Peter’s tomb after returning from his first journey to Central Africa: The Catholic, who is used to judging things in a supernatural light, looked upon Africa not through the pitiable lens of human interest, but in the pure light of faith; there he saw an infinite multitude of brothers who belonged to the same family as himself with one common Father in heaven (Writings 2742).

It is striking to note how St Daniel speaks of the poor, in a way very similar to that proposed by Pope Leo: No Christian can regard the poor simply as a societal problem; they are part of our “family”. They are “one of us” (104).

But the matter goes further.

The deep roots of love

Once again using the language of sight and seeing, and quoting Pope Francis, Pope Leo calls on all to respond to the poor person “with faith and charity”, seeing “in this person a human being with a dignity identical to my own, a creature infinitely loved by the Father, an image of God, a brother or sister redeemed by Jesus Christ” (106).

Daniel Comboni spoke of this same faith and charity in deep, experiential terms, telling how in his prayer at St Peter’s “he was carried away under the impetus of that love set alight by the divine flame on Calvary hill, when it came forth from the side of the Crucified One to embrace the whole human family; he felt his heart beat faster, and a divine power seemed to drive him towards those unknown lands. There he would enclose in his arms in an embrace of peace and of love those unfortunate brothers and sisters of his”.

The dynamic of transformation that pulses through these words of Comboni is also very much present in those of Pope Leo when he writes that “the problem of the poor leads to the very heart of our faith” (110), and says that “lives can actually be turned around by the realization that the poor have much to teach us about the Gospel and its demands” (109).

Living love

When Daniel Comboni returned to Khartoum after being ordained a bishop in Rome, he preached a memorable and moving homily to the flock entrusted to his care: “Rest assured that my soul responds to your welcome with unlimited love forever and for each one of you. I have returned among you never again to cease being yours and all consecrated for your greater good in eternity. Come day come night, come sun come rain, I shall always be equally ready to serve your spiritual needs: the rich and the poor, the healthy and the sick, the young and the old, the masters and the servants will always have equal access to my heart. Your good will be mine and your sorrows will also be mine. I make common cause with each one of you, and the happiest day in my life will be the one on which I will be able to give my life for you (Writings 3158-9).

The portrait of mission that Comboni painted in these words turns out to be a celebration of the call Pope Leo makes to the Church today in his Dilexi Te: mission to and for the poor as fundamentally a matter of love, a love that reaches across every divide of time and space, a love that confronts the apparently impossible and expresses itself in concrete action, presence and generosity, and that is as good for the giver as for the receiver. Against this background we can understand that Pope Leo draws his letter to a close with striking lines on the ongoing importance of almsgiving, and thus on a love which is practical, concrete and involves us personally, even if at times in apparently small ways.

As we conclude this journey with Pope Leo’s letter, and with the words and work of St Daniel Comboni vibrating in our hearts and minds, we do well to recall what the Pope says at the beginning of his reflection: “Love for the Lord, then, is one with love for the poor. The same Jesus who tells us, ‘The poor you will always have with you’ (Mt 26:11), also promises the disciples: ‘I am with you always’ (Mt 28:20). We likewise think of his saying: ‘Just as you did it to one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did it to me’ (Mt 25:40). This is not a matter of mere human kindness but a revelation: contact with those who are lowly and powerless is a fundamental way of encountering the Lord of history. In the poor, he continues to speak to us” (5).

Fr David Glenday,

Comboni missionary