Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

Friday, July 25, 2025

Missionary service, especially in a new linguistic and cultural context, begins with a process of (un)learning in order to open the way to the new world of the host culture into which the missionary must insert himself. In this initial process of deconstruction, Christ Jesus, the Father's missionary, is the paradigm.

A Christological hymn of the early Church proclaims that “[He] Who, being in the form of God, did not count equality with God something to be grasped. But he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, becoming as human beings are; and being in every way like a human being, he was humbler yet, even to accepting death, death on a cross” (Philippians 2:6-8).

At the beginning of every missionary sending is this process of humble stripping away of human and Christian experience, in order to welcome a new way of being a person and of believing, through language and culture, through living. I confess that it is challenging for an adult to accept becoming a child again and relearning life almost from scratch. However, without this “leap” it is not possible to carry out an inculturated mission and accept the host people as one's new homeland.

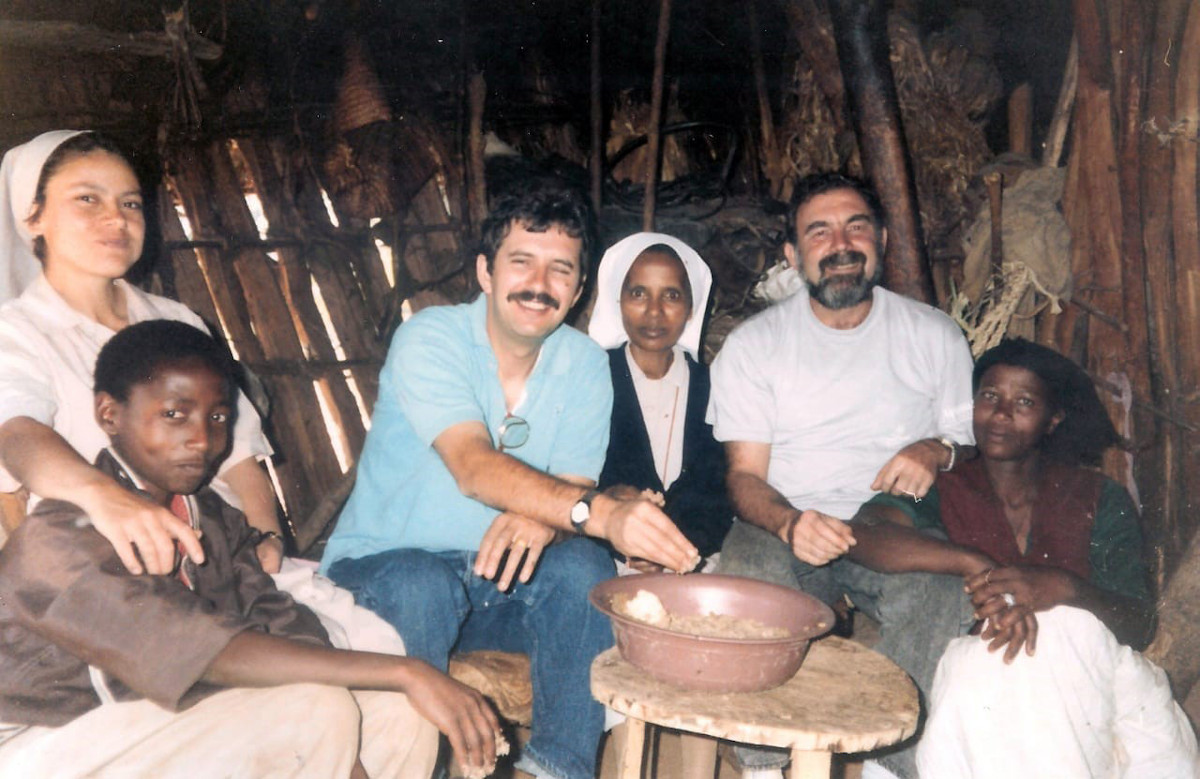

I was almost 33 years old when I first arrived in Ethiopia on January 9, 1993. Robe, a primary school teacher at the Qillenso mission, gave me my first lessons in Guji. Once I understood the mechanics of the language, I exchanged his lessons for socialising with the younger ones, who had no problem – unlike the adults – correcting and joking about my grammatical blunders.

It was complicated to try to stammer “good morning” in Guji – which literally means “Did you spend the night in peace?”– with the words playing hide and seek in the folds of my memory. Once, I was travelling to Addis Ababa (the Ethiopian capital), almost 450 kilometres away, on a mixture of dirt and asphalt roads. Halfway there, thirsty, I stopped at a shop on the side of the road. I wanted to ask for a soft drink (lasselasse) and ended up saying Trindade (Selassie). I realised my mistake when I saw the salesman's astonished look.

To learn the language, you have to lose your fear of making mistakes and try to think in the local language instead of doing simultaneous mental translation. The process takes time and requires a radical break with your mother tongue. This makes it difficult for “digital natives” – who spend much of their time connected to the internet in their own language – to learn the host language.

Inculturated evangelisation requires knowledge of the local culture. It helps a lot to illustrate the Gospel message with a proverb or a story. An elderly man, a neighbour of the Haro Wato mission, my second home in Ethiopia, was of fundamental support. In preparing for Sunday's homily, I would visit him to read the Gospel together, and then I would ask if there was a saying similar to Jesus' message. I still do this today, assisted by the cook – who, when she doesn't know, asks her father – and by a small collection of proverbs published by a Mexican colleague.

Another stimulating experience is learning how people refer to God in their own culture. The Gujis begin their traditional prayers by evoking God as “our father and mother, our grandfather and grandmother, our great-grandfather, the one who gave birth to us”. And they have many stories and proverbs about God. Using this language localises the Gospel message, diluting its foreignness.

The learning process is also physical. I am from Cinfães (in Northern Portugal), a village in the middle of the Montemuro mountain. I thought it was very high. Qillenso, my home in Ethiopia, is at an altitude of 2,300 metres, and it took my body almost a year to get used to the thin, humid air of the forest where we live. After a dozen years in these parts, I still feel a little dizzy when I celebrate in the chapel of Gosa, which is 2,800 metres above sea level.

There are other lessons to be learned: the rhythm of life (when there is no electricity, we go to bed with the chickens and get up with the roosters); giving time to encounters with people rather than to the agenda (in Africa, time is not counted, but made); discovering new concepts of justice and fairness (in a traditional reconciliation process, no one is entirely guilty and no one is completely a victim); slowing down daily life; local foods (which sometimes cause some intestinal upsets).

It is said that patience is the missionary's great shield. It is true: patience is learned and practised in the different processes in which we are involved. An African proverb teaches that alone we go faster, but together we go further! The Gujis say that “the egg slowly walked” to explain that the process of growth (from egg to chick) takes time.

The grammar of (un)learning may seem to be made up of losses, struggles and sacrifices. However, it is what makes missionary life the most privileged adventure to live, an experience of humanisation that leads the missionary to take on new ways of being human and of living God. Then, what we lack is what we have!