Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

In Pace Christi

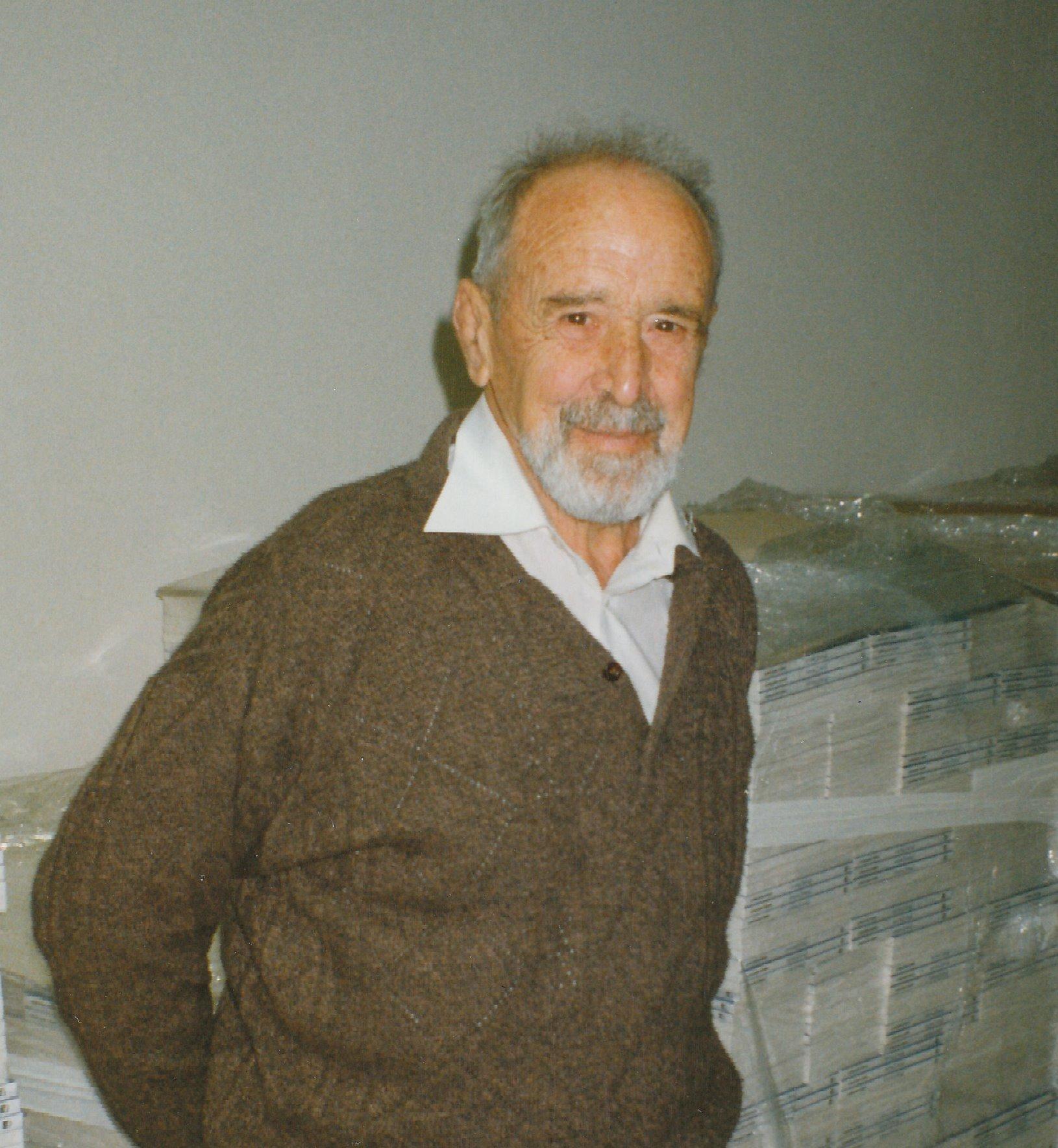

Spagnolo Lino

La tradizione missionaria comboniana nella famiglia Spagnolo di Recoaro, Vicenza, era ben affermata grazie a P. Lorenzo Spagnolo, “lo zio” (in relazione a P. Lino), che era entrato in noviziato a Verona nel 1908 e, sotto la guida di P. Vianello, era diventato un missionario di prima classe. Anche Lino, come “lo zio”, aveva lasciato il seminario diocesano scatenando le ire del vescovo, Mons. Ferdinando Rodolfi, che aveva assistito ad un’emorragia di ottimi seminaristi che si erano arruolati nelle file dei Comboniani.

La famiglia di P. Lino era costituita da papà Eto (“si chiamava proprio così, con una t sola, e non era di burro, precisò P. Lino in un’intervista) che di mestiere faceva il decoratore ma era anche maestro di bottega per alcuni giovani che da lui hanno imparato l’arte. La mamma, Maria Teresa Franceschini, era tutta presa dall’educazione dei quattro figli, due maschi e due femmine, dei quali Lino era il primo. Arrotondava lo stipendio del marito facendo l’affittacamere per coloro che andavano a Recoaro per la cura delle acque. La loro casa era chiamata “Canonica vecchia” perché in antico era stata l’abitazione del parroco. Nei mesi invernali l’intraprendente donna confezionava trapunte facendosi aiutare dalle figlie.

Lino veniva su svelto, intelligente e furbo, ma di una timidezza eccessiva. Di fronte ai compagni provava un complesso di inferiorità che cercava di superare nascondendosi. In compenso era buono, fedele alla messa tutte le mattine e ai sacramenti. Il parroco vide subito che in quel chierichetto che “stava sempre un passo indietro rispetto agli altri” c’era la stoffa del prete. E lo incamminò sulla via del sacerdozio facendolo entrare, a 11 anni, nel seminario diocesano.

Ma in casa arrivavano le lettere dello “zio” che nel 1919 era già a Kitgum e poi, dal 1920, a Rejaf dove insegnava il catechismo ai catecumeni e dava inizio all’orfanotrofio grazie ad un bambino salvato dalle acque del fiume, che venne chiamato Mosè. Queste cose influivano sull’anima del seminarista Lino e le raccontava con entusiasmo ai compagni di classe, come fossero capitate a lui.

Ma un altro fatto molto importante influì sulla vocazione di Lino. In seminario a Vicenza c’era un professore, Mons. Stocchiero, il quale ripeteva spesso ai seminaristi: “A queste finestre vanno tolte le inferriate, così che possiate uscire da qui per andare in tutto il mondo a predicare il vangelo”. Anche il padre spirituale gli dava man forte. I loro orizzonti erano quelli del mondo intero, non della loro piccola diocesi. Il Vescovo, però, non la pensava allo stesso modo per cui sia il professore che il padre spirituale furono allontanati dal seminario. Ma ormai la frittata era fatta e nove compagni di Lino erano già partiti per le missioni. Lino sarebbe stato il decimo.

Egli cominciò presto a parlare di vocazione missionaria ai suoi superiori, ma constatava che, ogni volta, il suo dire causava strane reazioni. E, sempre timido com’era, taceva e tirava avanti aspettando “la volta buona”. Finalmente arrivò alla fine di terza liceo. Immaginarsi che cosa disse e che cosa fece il Vescovo quando anche lui andò a dirgli che voleva farsi missionario!

La prima lettera di Lino ai Superiori dei Comboniani, nella quale parla di vocazione, è del 25 giugno 1929. Aveva frequentato il terzo corso di filosofia con ottimi voti. Comunicando la sua decisione allo zio che era in Africa, disse che nelle sue lettere dall’Africa aveva trovato tanti motivi per farsi missionario, che i giorni che lo separavano dal noviziato gli sembravano secoli... E poi si raccomandava alle sue preghiere e a quelle dei suoi moretti per diventare un bravo evangelizzatore.

Chiese ai Superiori di Verona di anticipargli l’entrata in noviziato “perché, essendo Recoaro luogo di villeggiatura, arrivano tante persone che portano solo scompiglio e distrazione”. Insomma, non sopportava la gente per casa.

Entrato in noviziato a Venegono Superiore nel 1929, emise la professione l’11 febbraio 1932 e poi passò a Verona per la teologia che frequentò nel seminario diocesano. In noviziato conobbe il giovane sacerdote trentino don Sisto Mazzoldi che aveva lasciato la parrocchia per farsi comboniano. Resteranno grandi amici per tutta la vita.

Lino fu ordinato sacerdote dopo la terza teologia, il sabato santo 31 marzo 1934, nella cattedrale di Verona da Mons. Girolamo Cardinale. Prostrati sul pavimento del presbiterio, accanto a lui c’erano altri 16 comboniani. In quegli anni ben nove di quelli che si erano prostrati su quel pavimento erano stati suoi compagni a Vicenza… P. Chiozza, P. Tagliapietra, P. Bevilacqua, P. Urbani, P. Fortuna, P. Besco, P. Caretta, P. Dal Maistro, P. Dal Maso martire…

Poi P. Lino passò a Venegono a terminare l’ultimo anno di teologia. Quale fu la sua sorpresa quando il vescovo di Vicenza, Mons. Rodolfi, andò a trovarlo per chiedergli perdono di averlo fatto tanto tribolare. “Eravate i migliori - tentò di giustificarsi - ecco perché mi opponevo”.

Trent’anni in Sudan meridionale

Il 7 ottobre 1934 P. Lino s’imbarcò a Genova sull’Esperia con i padri Domenico Cocci e Giuseppe Rosciano e i Fratelli Ignazio Rama ed Enrico Vanzo: la destinazione era il Bahr el Gebel. Giunsero a Juba l’11 novembre. Dopo alcune settimane di studio della lingua, P. Spagnolo venne destinato alla missione di Kapoeta come coadiutore di P. Sisto Mazzoldi, suo compagno di noviziato a Venegono.

Kapoeta, però, esisteva soltanto sulla carta. Il commissario distrettuale britannico, il capitano King, aveva concesso un pezzo di terra e si era impegnato a costruire le capanne. Il giorno di Natale del 1934 arrivò una sua lettera: “Le capanne sono pronte. Potete venire”. Mons. Zambonardi, P. Mazzoldi e i fratelli Faustino e Galli partirono immediatamente e arrivarono il 5 gennaio 1935. Il giorno dopo, festa dell’Epifania, celebrarono la prima messa. P. Lino fu mandato momentaneamente a Palotaka con P. Cereda per lo studio della lingua acioli. Gli avevano detto che a Kapoeta avrebbero trovato un grosso contingente di soldati acioli, molti dei quali erano cattolici e avevano bisogno di un sacerdote che conoscesse la loro lingua.

“Kapoeta - dice il diario di missione - dedicata a Maria SS. Addolorata, ha il compito di evangelizzare le tribù dei Toposa e dei Didinga. La regione è brulla, tolte le palme che in gran copia crescono gigantesche lungo il fiume Sinaeta. Il legname per le costruzioni è disponibile sulle lontane montagne dei Didinga. La popolazione è buona, ben disposta verso il missionario. Ci affrettiamo subito a scavare due pozzi in riva al fiume, lontano da casa circa un miglio. Il 30 gennaio arriva P. Lino Spagnolo insieme a Fr. Tobia Morcelli che pilota una nuovissima Guzzi con carrello. Deo Gratias”.

Dopo un mese trascorso a Palotaka, P. Lino parlava benissimo acioli per cui tornò alla missione alla quale era destinato. Fece tappa a Isoke dove c’era lo zio che aveva l’auto e anche una moto Guzzi dotata di cassonetto. Il nipote tanto disse e tanto fece, finché si fece regalare la moto e il guidatore (Fr. Morcelli) e, così equipaggiato, fece il suo solenne ingresso a Kapoeta.

Sfogliando il diario della missione, troviamo che il Padre si dedicava ai safari nei villaggi della zona, oltre che alla scuola. “… 8 maggio: dopo 16 giorni di assenza P. Lino ritorna dal suo viaggio apostolico tra i Didinga. Scopo principale del viaggio era di poter dare la possibilità di adempiere il precetto pasquale ai cristiani che, o impediti o per accidia, non sono venuti in missione per la Pasqua. Ha visitato tutti gli otto catecumenati sparsi in mezzo a quella tribù. Quattro cappelle-scuola sono già costruite e le rimanenti lo saranno quanto prima. Il concorso dei ragazzi per la scuola è abbastanza consolante. La gente ovunque è ben disposta ed è consolante constatare che i capi reclamano il Padre e la sua parola, opponendosi nettamente a qualsiasi infiltrazione da parte dei missionari protestanti”.

Il Padre, quindi, svolgeva il suo ministero in un clima di lotta con i protestanti che erano agguerriti e meglio forniti, quanto a mezzi, dei cattolici. “Ma i Toposa preferiscono noi cattolici perché siamo più vicini alla gente”, scrisse il Padre. Inoltre il capitano King, pur essendo protestante, stimava i cattolici e quando i protestanti insorsero contro i loro concorrenti, li cacciò dal distretto. “Non voglio guerre di religione”, disse.

“In settembre P. Lino - prosegue il diario - è partito per un safari tra i Longarim, che è riuscito molto bene”… “L’11 febbraio è la volta di un giro tra i Toposa con ritorno dopo una settimana”. Abbiamo visto in questo breve spazio come il Padre abbia dovuto affrontare tre tribù con lingue diverse. Ciò fa pensare quanto fosse difficoltoso quel ministero. Quanto al suo metodo missionario, era quello dei missionari della zona: accostare gli anziani e i malati, aiutare chi era nel bisogno, distribuire sale e tabacco e tirarsi attorno quanti più ragazzi fosse possibile convincendoli a frequentare la scuola di missione. Riscontrando che la terra non era adatta a trasformarsi in mattoni, il capitano King offrì ai missionari un posto alcuni chilometri più lontano. Ben presto sorsero bei fabbricati per la scuola e per il catecumenato, che si riempirono di ragazzi.

Intanto P. Lino cominciò a tradurre i vangeli della domenica e le preghiere in lingua locale. Dopo tre anni invia a Verona per la stampa la “Storia sacra in lingua Toposa”. E le conversioni non si fecero attendere. Il giorno dell’Immacolata del 1935 vennero amministrati i primi 59 battesimi.

Si potrebbe pensare che questo contatto con la gente in prima linea avesse scatenato in P. Lino una grande passione per il ministero diretto con la gente. Invece no. La timidezza che si portava dentro e che gli rodeva la vita come un tarlo, gli rendeva quel ministero assai difficoltoso.

In un brevissimo resoconto della sua vita missionaria, P. Lino scrisse di se stesso: “Dall’anno della mia ordinazione sacerdotale fino al presente (1970) la mia vita è sempre stata in missione, eccetto due periodi di vacanze e dopo l’espulsione dal Sudan (1964). Tra il 1964 e il 1965 ho frequentato l’anno di aggiornamento a Roma.

In missione la mia vita si è svolta in questo modo: coadiutore a Kapoeta dal 1934 al 1939, poi c’è stata la guerra con l’internamento, quindi sono passato come insegnante al seminario di Okaru dal 1942 al 1964; poi nuovamente insegnante al seminario minore di Nadiket (Moroto - Uganda) dal 1967 ad oggi. Credo che la mia vera vocazione sia quella dell’insegnamento”.

Siccome nella zona si parlavano 5 lingue diverse, i missionari si impegnarono a cambiare missione ogni tre anni in modo da imparare almeno tre idiomi diversi. Lino, che aveva il dono delle lingue, li imparò tutti e cinque diventando un esperto in acioli, toposa, lotuko, bari e madhi.

Ad Okaru

Mentre P. Lino si trovava a Kapoeta, ad Okaru (fondata come seminario nel 1928), fervevano i lavori per l’ammodernamento, anzi per la costruzione di un nuovo stabile, e necessitava di personale docente. I fratelli Zordan, Lazzari, Romanò e Spreafico davano il meglio di sé per quell’opera nella quale vedevano il futuro della Chiesa sudanese.

Okaru sorgeva sulla cima di un monticello, con un clima ideale, però era in zona estremamente selvaggia dove abbondavano le bestie feroci. Il diario registra: “Mentre gli studenti sono in gita scientifica a Juba, il leopardo fa una visita al pollaio. Ma l’impudenza gli costa la vita. E’ l’undicesimo leopardo che ci lascia la pelle. Il 7 ottobre 1934 fu giorno di grande festa. Mons. Zambonardi benedisse la prima pietra dell’erigendo edificio permanente del seminario che avrà la lunghezza di 90 metri e comprenderà tutti i locali necessari per un piccolo seminario ”.

“La monotonia della scuola - riporta il diario in luglio 1935 - è rotta dalla visita di messer leopardo il quale ha scoperchiato il tetto di tegole del pollaio, ha ucciso 35 galline e ne ha mangiate 8. Il giorno dopo, alle 7 di sera, era già in trappola. Era una bella bestia: dal naso alla coda misurava m. 2,40. E’ il quattordicesimo che pigliamo.

I racconti di fatti del genere si prolungano e si amplificano. Evidentemente trovavano il consenso, anzi il godimento, dei lettori. In quell’ambiente P. Lino trascorse i suoi 22 anni migliori perché vedeva la Chiesa sudanese che gli cresceva tra le mani ed egli si sentiva protagonista, insieme alla grazia di Dio, di quel miracolo. “Ho insegnato di tutto, eccetto matematica che mi è sempre stata ostica”, disse. Da altre fonti sappiamo che, durante il periodo di Okaru, il Padre dava una mano per l’apostolato tra la gente della zona. Come insegnante era metodico e meticoloso nel preparare le sue lezioni poiché, dice un giudizio dei superiori del tempo “è estremamente cosciente della responsabilità che è annessa al ministero di formatore dei futuri sacerdoti sudanesi”.

Poi venne la guerra e i missionari del Sudan meridionale furono confinati dagli inglesi nelle tre missioni di Isoke, Palotaka e Okaru. Solo nel 1946 P. Lino poté tornare in Italia per le prime vacanze. Al porto incontrò i confratelli che, dopo la guerra, andavano in missione a dare il cambio a coloro che avevano passato “la grande tribolazione”, senza personale, senza mezzi e, spesso, senza viveri.

Di una cosa P. Lino si vanterà sempre: la lunga lista di sacerdoti africani ai quali aveva impartito le sue lezioni. Tra essi c’erano ben tre vescovi: Mons. Paolino Lukudu, attuale arcivescovo di Juba, Mons. Ercolano Lado, vescovo di Yei e Mons. Vincent Mwajok, vescovo di Malakal

Emulo dello “zio”

Nel 1950 troviamo P. Lino a Loa, dove apprese anche la lingua Madhi, ma l’anno seguente era ancora in cattedra ad Okaru.

Mentre P. Lorenzo Spagnolo, “lo zio”, ha fatto il missionario di frontiera, il nipote ha sempre fatto l’insegnante. Il primo fu un grande studioso. Lasciò vocabolari e grammatiche in varie lingue. Il secondo tentò di emularlo, ma non era all’altezza anche se ha cercato di calcarne le orme. Di P. Lino, P. Novelli scrive: “Ha lavorato su un vocabolario di P. Farina traducendolo dall’italiano in karimojong e dal karimojong in italiano. Quando era ancora in Sudan ha fatto una grammatica toposa, di cui una copia pare esista ancora nella casa del Vescovo di Juba. A questi suoi lavori linguistici P. Lino si è dedicato fino agli ultimi anni della sua permanenza in Africa. Aveva la fama di essere un po’ scorbutico, un po’ misantropo, e forse lo era, tuttavia ho trovato in lui una delicatezza straordinaria con coloro che riteneva suoi amici. Non c’era pericolo, per esempio, che passasse un compleanno o un onomastico senza che arrivassero gli auguri e le preghiere di P. Lino”.

“Io ricordo la sua generosità - dice P. Soriani. - A 30 Km da Palotaka, nel Bahr el Gebel, c’è un fiume che in quei giorni era in piena. P. Lino doveva attraversarlo con il suo furgoncino. Ha tentato più volte, ma ha dovuto desistere per la veemenza delle acque. Allora ha mandato un paio di giovani alla missione chiedendo aiuto. Costoro ci dissero che il Padre era annegato. Presi il camion, alcuni giovani con delle corde e via verso il fiume con l’angoscia nel cuore. Ma, giunti alla sponda, abbiamo visto su quella opposta il Padre tranquillamente seduto che aspettava.

‘Cosa mi hanno detto, questi qua!’, protestai.

‘Sai, i Neri esagerano sempre’, commentò dopo che ebbe saputo ciò che avevano raccontato. E ridacchiava con fare malizioso per cui pensai che l’autore della bugia fosse proprio lui per costringerci a muoverci in fretta per andare in suo soccorso.

I giovani legarono l’auto col Padre dentro e lo trainarono dall’altra parte. P. Lino volle mostrare la sua riconoscenza lasciandoci una cassa di birra e due galloni di benzina, materiale prezioso in quel periodo di carestia”.

Nel 1964 fu tra gli espulsi dal Sudan meridionale. Si trovava casualmente a Juba e dovette partire senza poter tornare ad Okaru a prendere le sue cose. Non gli pareva vero, dopo 30 anni di lavoro per quel Paese. Ed ebbe una reazione un po’ forte, quasi violenta. Il poliziotto lo fece zittire immediatamente puntandogli il mitra al petto. Vedendo che con gli africani non c’era da scherzare, giunto all’aeroporto di Khartoum se la prese con gli italiani. ‘Dov’è l’ambasciatore d’Italia? Cosa sta facendo a quest’ora? - gridò - siamo in cinquecento che vengono espulsi come appestati e qua nessuno si fa vivo!’. Non sapeva, il Padre, che la politica italiana era filo araba. Quando aprì la borsa che un confratello gli aveva preso in camera, ebbe un attimo di sgomento: c’erano solo un paio di calzoni e una maglietta. ‘E la grammatica e la sintassi della lingua toposa pronta per la stampa?’, chiese. Anni di lavoro buttati al vento”.

15 anni in Uganda

Dopo l’anno di aggiornamento a Roma (1964-65) chiese di poter andare a Moroto, in Uganda dove c’era il suo primo compagno di missione e amico carissimo Mons. Sisto Mazzoldi, già vescovo di Juba ed ora della nuova diocesi staccatasi da quella di Gulu. A Gulu c’era anche lo “zio” che insegnava teologia morale nel seminario maggiore.

Mons. Mazzoldi, per prima cosa appena messo piede nella nuova diocesi, eresse il seminario. Scelse la zona di Nadiket e poi cominciò a cercare gli insegnanti. P. Lino giunse come il formaggio sui maccheroni. Appena giunto nella nuova missione il Padre scrisse al superiore generale: “La ringrazio del grande favore concessomi di potermi trovare al presente ancora in terra di missione a lavorare direttamente a vantaggio di questa povera gente che sta cercando la strada della salvezza”. Insegnò nel seminario ma, nei giorni di vacanza, inforcava la moto e via a Moroto a trovare il suo amico e a fargli da segretario specialmente per la stesura delle lettere.

Nel 1968, proprio a Moroto, Mons. Mazzoldi insieme a P. Marengoni fondò le congregazioni degli Apostoli di Gesù e delle Suore Evangelizzatrici. Era un modo molto efficace di attuare il Piano di Comboni: salvare l’Africa con gli Africani, ripreso e dilatato da Paolo VI che, nel 1969, a Kampala, invitò gli Africani ad essere i missionari dei loro fratelli.

Nel 1981 Monsignore lasciò la diocesi per raggiunti limiti di età e si ritirò a Nairobi con P. Marengoni nella sede degli Apostoli di Gesù. P. Lino, privato del suo vescovo e amico, provò un senso di smarrimento e chiese di essere trasferito in Kenya.

In Kenya P. Mario Porto

I due provinciali, quello d’Uganda (P. Guido Miotti) e quello del Kenya (P. Giovanni Ferracin) si dissero d’accordo. Qualche obiezione, invece, venne da P. Marengoni il quale, in data 14 luglio 1981 scrisse: “Sono disposto a ricevere P. Lino come confratello che chiede di essere ricevuto e volentieri gli do ospitalità se non c’è altra soluzione. P. Lino non dovrebbe essere considerato addetto agli Apostoli perché non trovo un lavoro adatto per lui”. Ma il posto per lui saltò fuori ben presto. Infatti andò a Langata nello studentato filosofico e teologico degli Apostoli di Gesù, vivendo sempre all’ombra di Mons. Mazzoldi. E’ interessante una cosa accaduta in questo periodo, apparentemente insignificante, ma merita di essere riportata perché è la prima e l’unica che sia capitata tra i confratelli. Sentiamo la letterina che P. Lino scrisse al superiore provinciale in data 11 settembre 1981.

“Ho una difficoltà. Lei sa che io fumo (fumava una sigaretta dopo pranzo e una dopo cena e basta, n. d. r.). Ora la mia comunità è a corto di soldi dovendo comperare una nuova macchina, perciò vogliono ridurmi la moneta per comperarmi le sigarette. Lei mi aveva promesso, tempo fa, che in caso di necessità mi rivolgessi a lei per un sussidio. Ora è il momento giusto…”.

Beh! Sappiamo che la sorella Luigina era solita mandargli parecchi soldi. Ella andò anche a trovarlo in Kenya lasciandogli, in una volta, otto milioni. Di fronte a questa lettera c’è solo da ammirare la delicatezza di coscienza in fatto di povertà e di obbedienza di questo nostro confratello. Diventava “feroce” con coloro che, al contrario, avevano l’auto personale e il conto in banca, pure personale. Ci sono lettere terribili contro questo “mal vezzo che dilania la carità fraterna e il bel vivere che deve sempre regnare in provincia, a causa dei sporchi soldi, sterco del diavolo… Meglio poveri e in buon armonia, che ricchi col muso lungo un metro e mezzo”. Sono parole sue, scritte il 24 dicembre 1986 con nomi e cognomi.

Per il 50° di sacerdozio, 1984, gli fu concesso un pellegrinaggio in Terra Santa. “Sono stati veri esercizi spirituali”, scrisse. Complessivamente rimase accanto a Mazzoldi per 17 anni, come suo segretario e insegnante. Come segretario era ideale: fedele, preciso, sempre disponibile e ben preparato. Era suo compito mantenere la fitta corrispondenza che il Vescovo aveva con tante persone in Africa e in Italia per reperire i mezzi idonei a mandare avanti i suoi istituti.

Nella comunità di Langata, oltre ad essere a disposizione del Vescovo, offriva il suo contributo alla formazione dei numerosi studenti di filosofia e teologia, circa 200, come confessore e direttore spirituale, da tutti apprezzato e ricercato per il suo spirito di servizio, per la sua comprensione e l’ampia esperienza pastorale.

P. Bruno Ramazzotti lasciò scritto: “Mi colpì in P. Lino la solida vita di preghiera. Ogni mattina alle 5 era in chiesa per la meditazione e la santa messa. Come alla liturgia eucaristica, era fedele alla liturgia delle ore ed edificava gli studenti per il suo assiduo stare in adorazione davanti al Santissimo”.

Ancora solo

Il 27 luglio 1987 Mons. Mazzoldi morì e P. Lino si trovò ancora una volta solo e spaesato. P. Marengoni che aveva capito il valore dell’uomo gli disse: “Il tuo posto è qui”. E P. Lino indicò sì con il gesto del capo.

Quando gli Apostoli di Gesù elessero il loro superiore generale e P. Marengoni si ritirò a Rongai, presso Nakuru, a 150 chilometri da Nairobi dove diede vita a una seconda congregazione missionaria I missionari contemplativi del Cuore di Gesù, P. Lino si ritirò nella casa provincializia dei Comboniani di Nairobi. Scrivendo a P. Marengoni, gli disse telegraficamente: “Non ti servo proprio più?”. “Mi servi sempre”, gli rispose il confratello. Siamo nel 1991. P. Lino a 81 anni ebbe ancora la grinta di buttarsi in una nuova avventura: dare una mano come confessore e padre spirituale dei membri del nuovo istituto. “E’ una mano un po’ fiacca, a dire la verità - riconobbe - per le necessità di un nuovo istituto missionario”. Invece lavorò molto bene, sottolineando lo spirito del nuovo istituto con l’austerità della vita e prolungate ore di preghiera.

Nel 1991 partiva per le vacanze. “Mi porto in tasca la chiave della stanza di Rongai. Ho lasciato tutta la mia roba là perché è là che tornerò fra tre mesi. Mi aspettano. E questo lo devono sapere tutti. Che non venga in mente a qualcuno la pazza idea di trattenermi in Italia con la scusa che sono vecchio”.

Invece, mentre era a Recoaro, ricevette la lettera del suo Provinciale, P. Santiago, nella quale veniva invitato a restare in Italia “perché vari confratelli hanno espresso obiezioni a delle sue espressioni e scherzi”. “Dopo 57 anni di Africa mi si dice questo? Prendo la cosa in sconto dei miei peccati, ma la carne si ribella. Non potete accusarmi a distanza senza darmi la possibilità di difendermi… La piaga infertami dalla ferita alla schiena stenta a rimarginarsi”, scrisse con molta ammarezza.

Il vecchio amico Marengoni gli aprì ancora una volta le braccia e P. Lino poté tornare, non a Ngong Road (sede della casa provincializia) ma a Rongai con gli Apostoli di Gesù.

E questo vecchio missionario, consapevole dei suoi limiti, animato da sincera umiltà e sempre in tensione per camminare verso la perfezione religiosa, scrisse i suoi propositi:

“Oggi, festa di Santa Marta 29 luglio 1991, ho chiesto al Signore che mi aiuti a mettere in pratica i seguenti propositi:

-

Praticherò generosa ospitalità per accogliere Gesù negli altri.

-

Servirò il prossimo in necessità come se lo facessi a Gesù.

-

Sarò sollecito nell’operare il bene con cuore e viso aperti.

-

Accoglierò l’ospite come Gesù che viene a riposarsi in casa mia”.

Insomma, era davvero commovente l’atteggiamento di questo vecchietto quasi troppo vispo per la sua età, ma altrettanto disponibile a cercare continuamente la volontà del Signore.

Trascorsero altri tre anni e giunse il 1994, anno in cui il Padre celebrava il suo 60° di sacerdozio. Al suo paese lo aspettavano per grandi festeggiamenti. Il nuovo P. provinciale, P. Fernando Colombo, lo mandò in Italia dove “P. Lino prevede di fermarsi tre mesi. Non ha bisogno di cure mediche perché sta bene”, scrisse.

Fatte le feste tornò nuovamente in Kenya, a Rongai e vi rimase per un anno. Nel frattempo la sorella Luigina andò nuovamente a trovarlo. Poi il Padre scrisse al provinciale che era disposto a tornare nella casa provincializia “onde essere di aiuto a quella comunità per quanto posso alla mia età. Mi rimetto totalmente alla sua volontà sicuro di fare la volontà di Dio”. Il Signore lo preparava al distacco dalla sua Africa. Infatti, nel 1996 P. Lino dovette essere ricoverato d’urgenza all’ospedale “perché sembra semiparalizzato”, scrisse P. Colombo. I sanitari consigliarono il ritorno in Italia e il Padre, questa volta, non oppose resistenza.

Nella messa di addio, celebrata nella cappella di casa, in Kenya, disse: “Io voglio essere sepolto in Africa”. Era sicuro che, dopo essersi ripreso, sarebbe tornato anche questa volta.

Giunse a Roma giovedì 18 aprile, accompagnato dai confratelli Fr. Cesaro e P. Pasinetti. Fu accolto a Verona dove si sentiva “a casa sua” e si riprese abbastanza bene. Un anno dopo scriveva a P. Milani: “Con questa mia faccio domanda di essere assegnato alla Provincia italiana. Accetto volentieri di essere mandato in una delle nostre comunità anche se preferirei, per il momento, fermarmi a Verona dove sono stato accolto e seguito con grande attenzione e fraternità”.

I suoi ultimi anni furono una continua preghiera e un vivere per le missioni, tanto che i confratelli commentavano: “In Italia ha fatto il suo purgatorio”.

Un carattere particolare

P. Lino Spagnolo è forse uno dei pochi sacerdoti comboniani che non è mai stato superiore neanche per un giorno. Era uno che non ci tenne mai ad esserlo. Anzi, rifuggiva in tutte le maniere il solo mettersi in mostra. Egli amava fare il suo lavoro di insegnante, prima, e di segretario di mons. Mazzoldi, dopo, senza impicciarsi in decisioni o direttive che lasciava volentieri agli altri.

Abbiamo già detto che fu assai timido di carattere. E ciò gli fu causa di grande sofferenze e di incomprensioni da parte degli altri. Per esempio, quando nella sua missione arrivava un confratello, magari da lontano, certamente stanco e affamato, egli, invece di andargli incontro festante, si nascondeva per non farsi vedere. E se proprio doveva incontrarlo ere capace di dirgli: “Cosa sei venuto fare qui?” mettendo a disagio l’ospite. Ma la cosa più commovente era quando, poco dopo, si vedeva questo anziano che si presentava al nuovo arrivato con le lacrime agli occhi e gli chiedeva perdono della scortesia di poco prima.

Questa sua debolezza, che poi finiva per rivelare la sua umiltà, gli fu motivo di una grande sofferenza e confusione fino a fargli spremere lacrime dagli occhi.

E’ morto a Verona il 22 agosto 2000 ed è stato sepolto al suo paese. Il nuovo Provinciale del Kenya, che ha tenuto l’omelia al funerale, ha detto: “Quest’uomo si è presentato al tribunale di Dio con le mani piene di meriti. Ha avuto una grande fiducia negli Africani; per loro e per la Chiesa africana ha dato la sua vita”.

Tratti caratteristici di P. Lino sono stati: una costante serenità di spirito, mantenuta anche in situazioni difficili e alimentata da una robusta fede, e l’abituale disponibilità dimostrata nel portare avanti con serietà e impegno i diversi compiti a lui affidati dai Superiori. Che dal Cielo interceda per la Chiesa del Sudan, dell’Uganda e del Kenya. P. Lorenzo Gaiga

Da Mccj Bulletin n. 209, gennaio 2001, pp. 143-153

++++++

The Comboni Missionaries' tradition was solidly rooted in the Spagnolo family of Recoaro, Vicenza, thanks to Fr. Lorenzo Spagnolo, Lino’s uncle, who had entered the novitiate in Verona in 1908 and under the guidance of Fr. Vianello had become a first class missionary. Lino, like his uncle, left the diocesan seminary, which angered the bishop, Mgr. Ferdinando Rodolfi, as he had seen many good seminarians leave the diocesan seminary to enrol in the ranks of the Comboni Missionaries.

Lino’s father, Eto, was a decorator and had his own workshop where he taught this trade to some young boys. His mother, Maria Teresa, looked after her four children, two boys and two girls. Lino was the first child. To increase the family’s income, Lino’s mother rented out rooms to people who came to Recoaro for the thermal water’s treatment. Their house was called the “old rectory”, as in the past it had been the home of the parish priest. In the winter months, this enterprising woman and her daughters made quilts.

Lino was a bright boy, but was very shy and had an inferiority complex. When he was with his friends, he tried to overcome this defect by hiding himself. He was a good boy who attended Mass every morning. The parish priest saw that this altar boy, who “was always one step behind the others”, had the makings of a priest. He helped him along this path and, at the age of eleven, Lino entered the diocesan seminary.

His missionary uncle wrote to his home. In 1919 he was in Kitgum and in 1920 in Rejaf, where he taught catechism to the catechumens. He also started an orphanage, thanks to a small boy, who was saved from drowning in the river and who was later named Moses.

These letters influenced the seminarian, Lino, and he talked about the events narrated by his uncle to his school friends as if they had happened to him.

But there was another factor, which influenced Lino’s vocation. In the seminary of Vicenza, there was a teacher, Mgr. Stocchiero, who often repeated to the seminarians: “The bars must be removed from these windows, so that you may go out from here and spread out to preach the Gospel all over the world”. His spiritual director also encouraged him. The horizons of these two good priests were those of the whole world, not just the diocese. The Bishop, however, did not think this way and both the teacher and the spiritual director were sent away from the seminary. Nine of Lino’s fellow seminarians had already left for the missions. Lino would be the tenth.

Lino began to talk about his missionary vocation to his superiors, but he realized that every time he did this, it caused strange reactions. As he was shy, he kept quiet and waited for the right time.

This arrived at the end of the third year of secondary school. You can imagine what the bishop did and said when Lino told him that he wanted to be a missionary!

Lino first wrote to the superiors of the Comboni Missionaries on 25 June 1929. He had finished the third year of philosophy and had received excellent marks. He wrote to his uncle in Africa about his decision and told him that in his letters he had found many reasons for becoming a missionary and that the days which separated him from the novitiate seemed like ages. He asked his uncle to remember him in his prayers so that he would become a good missionary priest.

He asked his superiors in Verona to anticipate his entrance into the novitiate “because Recoaro was a tourists’ resort and these tourists brought only confusion and distraction.” In fact, he couldn’t stand having guests in his house.

He entered the novitiate in Venegono in 1929. He took his first vows in February 1932 and then attended theology at the diocesan seminary in Verona. In the novitiate, he met a young priest from Trento, Fr. Sisto Mazzoldi, who had left his parish to become a Comboni Missionary. They would remain good friends for the rest of their lives. Lino was ordained to the priesthood after the third year of theology by Mgr. Girolamo Cardinale in the cathedral of Verona on Holy Saturday, 31 March 1934.

Sixteen other Comboni Missionaries were prostrated with him on the floor in front of the altar. Nine of these had been his companions in Vicenza: Fr. Chiozza, Fr. Tagliapietra, Fr. Bevilacqua, Fr. Urbani, Fr. Fortuna, Fr. Besco, Fr. Caretta, Fr. Dal Maistro and the martyr Fr. Dal Maso…

After his ordination, Fr. Lino went to Venegono for the last year of theology. One day, to his great surprise, the bishop of Vicenza, Mgr. Rodolfi, came to visit him to ask him forgiveness for having been opposed to his missionary vocation. He tried to justify himself by saying: “I was against you becoming missionaries, because you were the best seminarians I had in those days.”

Thirty years in South Sudan.

On 7 October 1934, Fr. Lino sailed from Genoa on the boat Esperia with Fr. Domenico Cocci, Fr. Giuseppe Rosciano, Bro. Ignazio Rama and Bro. Enrico Vanzo. They were going to Bahr el Gebel. They reached Juba on 11 November. Fr. Spagnolo studied the local language for a few weeks and was then sent to the mission of Kapoeta as assistant to Fr. Sisto Mazzoldi, his fellow novice in Venegono.

Kapoeta, however, existed only on the map. The British district commissioner, captain King, had granted the missionaries a piece of land and had built a few huts. On Christmas Day, 1934, a letter of his arrived: “The huts are ready. You may come.” Mgr. Zambonardi, Fr. Mazzoldi, Bro. Faustino and Bro. Galli left immediately and arrived at Kapoeta on 5 January 1935.

The day after, the Feast of the Epiphany, they celebrated the first Mass. Fr. Lino was sent to Palotaka with Fr. Cereda to study Acholi. They had told him that in Kapoeta there was a large contingent of Acholi soldiers, many of whom were Catholics and needed a priest who knew their language.

In the mission’s diary it is written that: “Kapoeta is dedicated to Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows and was established to evangelise the Toposa and Didinga tribes. The region is barren except for the giant palms, which grow along the river Sinaeta. Wood for construction is found far away in the mountains where the Didinga live. The people are good and willingly accept missionaries. We will dig two wells along the banks of the river, about a mile from the house. On 30 January, Fr. Lino arrived with Bro. Tobia Morcelli who drove a new Guzzi motorbike with a sidecar. Deo Gratias!”

After a month in Palotaka, Fr. Lino could speak Acholi very well and so he returned to the mission he had been assigned to. He stopped in Isoke where his uncle had a car and a Guzzi motorbike with a sidecar. The nephew convinced his uncle to give him the motorbike and the driver (Bro. Morcelli) and so equipped he made his formal entrance into Kapoeta.

In the mission diary we learn that he visited the villages in the area and taught in the local school. “… 8 May. After sixteen days Fr. Lino has returned from his apostolic trip among the Didinga. The main reason for his trip was to give the Christians, who had not come to the mission, the possibility to fulfil their Easter duty. He visited each of the eight chapels in the area. Four schools have already been built and others would soon be ready. The attendance of the students at the schools is quite encouraging. Everywhere the people are hospitable to missionaries and it is heartening to learn that the leaders accept Fr. Lino and his words, and clearly oppose any approach made to them by Protestant missionaries”.

Fr. Lino in his ministry had to struggle against the Protestants, who were strong and better equipped than the Catholics. “But the Toposa prefer us Catholics, as we are closer to the people”, he wrote. Captain King, although a protestant, respected the Catholics and when the Protestants started quarrelling with their rivals, the captain asked them to leave the district. “I don’t want a religious war”, he said.

As we continue to read the mission diary we learn that: “In September, Fr. Lino made a very successful safari among the Longarim people.”…. “On 11 February he started a safari for a week among the Toposa.” In a short time Fr. Lino had to deal with people who spoke three different languages. This made his ministry rather difficult. His pastoral method was the same used by the other missionaries working in that region. It consisted in approaching the elderly and the sick, helping the needy, distributing salt and tobacco, attracting as many boys as possible and convincing them to attend the mission school. As nearby there was no clay suitable for making bricks, captain King gave the missionaries a place a few kilometres away where it could be found. Soon a school and a building for the catechumens were constructed and these were filled with boys.

Fr. Lino began to translate the Sunday Gospels and prayers into the local language. After three years, he sent “The Holy Bible in Toposa” to Verona to be printed. People converted and on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception of 1935, fifty-nine baptisms were administered.

One would think that this contact with people would have aroused in Fr. Lino a passion for the pastoral work. But it was not so. His shyness, which gnawed deeply inside him like a worm, made this work very difficult for him.

In a very brief account of his missionary life, Fr. Lino wrote: “From my ordination to the present (1970), I have spent my life in the missions, except for two vacation periods and after I was expelled from Sudan (1964). From 1964 to 1965 I attended the renewal course in Rome.

“I have worked in the missions as assistant parish priest at Kapoeta from 1934 to 1939. When the war started, we were interned and after I became a teacher in the seminary of Okaru from 1942 to 1964. From 1967 to the present I have worked in the minor seminary of Nadiket (Moroto-Uganda). I think that my real vocation is to teach.”

As five different languages were spoken in the area of his first mission, the missionaries changed mission every three years to learn at least three of them. Lino, who had the gift of languages, learned all five and became an expert in Acholi, Toposa, Lotuko, Bari e Mahdi.

In Okaru

While Fr. Lino was at Kapoeta, the construction of a new building began at Okaru (founded as a seminary in 1928) and there was a need for teachers. Bro. Zordan, Bro. Lazzari, Bro. Romanò and Bro. Spreafico did their best to construct this seminary as they saw in it the future of the Church in Sudan.

Okaru is situated at the top of a small mountain, where the climate is ideal, but it is an area where there are many wild animals. In the mission diary, the following event is recorded: “While the students were on a science trip to Juba, a leopard got into the poultry pen. But with this bold action it lost its life. It is the eleventh leopard to be killed. On 7 October 1934 there was a special ceremony. Mgr. Zambonardi blessed the first stone of the building that would become the seminary. It would be 90 metres long and have all the necessary facilities of a small seminary.” In July 1935 the diary reports: “The daily activity of the school is interrupted by a leopard’s visit to the poultry pen. It took the roof off, killed 35 hens and ate 8 of them. The next day, at 7 o’clock in the evening, it had been caught. It was a beautiful animal: from the nose to the tail it measured 2.40 metres. It is the fourteenth leopard that we have caught.”

Stories of this type get longer and in ever-greater details. Obviously the readers enjoyed them. It was in this environment that Fr. Lino spent twenty-two years, the best years of his life because he saw the Church in Sudan grow and felt that he, together with God’s grace, was a protagonist in this miracle. “I taught all subjects except math, which was always difficult for me”, he said. From other sources we have learned that Fr. Lino, during this period, helped the priests who did pastoral work. As a teacher he was methodical and meticulous in preparing his lessons and his superiors at that time said: “He is extremely conscious of the responsibility he has as a formator of the future Sudanese priests.”

Then war broke out and all the missionaries in South Sudan were confined by the English to the missions of Isoke, Palotaka and Okaru. It wasn’t until 1946 that Fr. Lino could return to Italy for his first holidays.

When he disembarked at the arbour, he met his confreres who were going to the missions to take the place of those who had survived “the great hardship” without help, without means and often without food.

Fr. Lino would always be proud of the many Africans priests he had taught. Among these, there were three bishops, i.e. the present archbishop of Juba, Mgr. Paolino Lukudu, Mgr. Ercolano Lado, bishop of Yei and Mgr. Vincent Mwajok, bishop of Malakal.

Following the example of his uncle

In 1950 Fr. Lino was in Loa, where he learned also Mahdi, but the following year he was back in the seminary of Okaru.

While his uncle, Fr. Lorenzo Spagnolo, was always a frontier missionary, Fr. Lino, his nephew, was always a teacher. The first was a renowned scholar, writing dictionaries and grammars in various languages. The second tried to emulate him and follow in his footsteps, but he wasn’t up to doing this type of work. Fr. Novelli wrote about a Fr. Lino: “He worked on a dictionary written by Fr. Farina and translated it from Italian into Karimojong and from Karimojong into Italian. While he was in Sudan he wrote a Toposa grammar and there is still one copy of this book in the bishop’s house in Juba. Fr. Lino continued these linguistic endeavours during his entire permanence in Africa. He was considered a little sullen, a little unfriendly and perhaps he was; however I found him extremely sensitive with those he considered his friends. A birthday or a feast day would never go by without Fr. Lino sending his best wishes and prayers.”

“I remember his generosity”, said Fr. Soriani. “Thirty kilometres from Palotaka, in Bahr el Gebel, there is a river, which in those days was in flood. Fr. Lino had to cross it with his van. He tried several times, but had to give up because of the strong currents. Then he sent two boys to the mission to ask for help. They reported that Fr. Lino had drowned. I threw some ropes into the truck and I anxiously drove to the river with some young men. When we reached it, we saw Fr. Lino waiting peacefully on the opposite bank. “But these boys told me you had drowned”, I protested.

“You know that African always exaggerate”, he said. He grinned mischievously, which made me think that he was the author of this lie. He wanted to force us to come quickly to his aid.

“The boys tied a rope to the van and pulled it safely to the other side. Fr. Lino showed his gratitude by giving us a case of beer and two gallons of petrol, which were very precious at that time when everything was in short supply.”

In 1964 he was among those expelled from South Sudan. He was visiting Juba and couldn’t return to Okaru to get his belongings. It could not believe that such a thing could happen to him after thirty years of work in that country. He reacted strongly, almost violently. A policeman quieted him quickly by pointing a machinegun to his chest. Seen that he couldn’t get anywhere with the Africans, he got angry with the Italians at the airport of Khartoum. He started shouting at them: “Where is the Italian Ambassador? What is he doing now? There are 500 of us being expelled as if we have the plague and no one is here to see what happen.” He didn’t know that the Italian government was pro-Arab. When he opened his bag, which a confrere had fetched for him in his room at Okaru, he was dismayed: there was only a pair of trousers and a T-shirt. He asked: “And where is my Toposa grammar and syntax which is ready to be printed?” Years of work had been lost forever!

Fifteen years in Uganda

After a year of renewal in Rome (1964-65), Fr. Lino asked to go to Moroto, in Uganda, where his dear friend and first mission companion, Fr. Sisto Mazzoldi, was now bishop of that new diocese, recently carved out from that of Gulu. In Gulu there was his uncle, teaching at the major seminary.

As soon as Mgr. Mazzoldi arrived in his new diocese, he had a seminary built near Nadiket. Then he began to look for teachers. Fr. Lino’s arrival at the seminary was like the icing on the cake. Immediately after reaching Nadiket, Fr. Lino wrote to the Superior General: “Thank you for sending me once again to the missions to work for these poor people and help them find the road to salvation.” He taught at the seminary, but on his days off, he took his motorbike and went to Moroto to visit his friend and to work as his secretary, drafting letters.

In 1968, in Moroto, Mgr. Mazzoldi and Fr. Marengoni founded the Congregations of the Apostles of Jesus and of the Evangelising Sisters. This was the most effective way of realizing Comboni’s plan: to save Africa with Africans. Paul VI renewed this plan in 1969 in Kampala, when he invited Africans to be missionaries to other Africans.

In 1981 Mgr. Mazzoldi left the diocese as he had reached the retiring age set for bishops and together with Fr. Marengoni went to live with the Apostles of Jesus in Nairobi. Fr. Lino, without the presence of his bishop and friend, felt lost at Nadiket. Therefore he asked to be transferred to Kenya.

In Kenya

The two provincial superiors, Fr. Guido Miotti of Uganda and Fr. Giovanni Ferracin of Kenya, agreed to his transfer. Fr. Marengoni on 14 July 1981 wrote: “I am willing to accept Fr. Lino as a confrere and to offer him hospitality, if there is no other solution. But Fr. Lino should not consider himself working for the Apostles of Jesus, because I have not found a job suitable for him.”

But a job for Fr. Lino was soon found. He went to Langata, where he worked with the philosophy and theology students of the Apostles of Jesus, alongside Mgr. Mazzoldi. Fr. Lino wrote to the Provincial Superior on 11 September 1981. The fact described in this letter merits our attention, as it is the only one of its kind to happen to our confreres.

“I, Fr Lino have a problem. As you know I smoke (he smoked a cigarette after lunch and one after dinner). Since my community is short of funds and there is a need to buy a new car, they want to reduce the pocket money I can spend on cigarettes. You promised me, some time ago, that if I ever needed anything, I could ask your help. Now the time has come…”

We know that his sister, Luigina, usually sent him quite a lot of money. She also went to visit him in Kenya and one time she gave him Lit. 8 million. With respect to the above letter, we can only admire Fr. Lino’s sensitive conscience with regard to his vows of poverty and obedience. He became furious with those confreres who had their own car and a personal bank account. There are angry letters of his written against this bad habit, “which ruins the brotherly love and the good way of life that should always reign among us. It is better to be poor and live in harmony than to be rich and have a long face.” These are his words written on 24 December 1986.

For the 50th anniversary of his priestly ordination in 1984, he was granted a trip to the Holy Land. “Here, in the Holy Land, I was able to do real spiritual exercises,” he wrote. He worked with Mgr. Mazzoldi for a total of seventeen years as a secretary and as a teacher. As a secretary he was ideal: faithful, precise, compliant and well prepared. It was his job to maintain the correspondence that the bishop had with many people in Africa and in Italy and who helped him support his Institutes.

In Langata, Fr. Lino worked not only with the bishop, but also with the 200 philosophy and theology students as their confessor and spiritual director. He was respected and solicited because of his spirit of service, his sensitivity and his broad pastoral experience.

Fr. Bruno Ramazzotti wrote: “Fr. Lino’s solid prayer life impressed me. Every morning at 5 o’clock he was in church for meditation and Mass. He was faithful to the Eucharist and to his breviary. His untiring adoration of the Blessed Sacrament set an example for the students.”

Alone

Mgr. Mazzoldi died on 27 July 1987 and Fr. Lino found himself once again alone and lost. Fr. Marengoni, who understood his value, told him: “Your place is here”. Fr. Lino nodded his assent.

When the Apostles of Jesus elected their own Superior General, Fr. Marengoni retired to Rongai near Nakuru, 150 kilometres from Nairobi. There he founded a second missionary congregation, The Contemplative Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Fr. Lino went to live in the Comboni provincial house of Nairobi. He wrote to Fr. Marengoni: “Can I help you?” “You can always help”, answered Fr. Marengoni. It was 1991. Fr. Lino at the age of 81 still had the determination to embark on another adventure: he helped out as a confessor and spiritual director to the members of the new Institute. He realized that: “He was a little tired to take care of all the spiritual needs of a new missionary institute:” Instead he worked very well as he lived the spirit of the new institute by his austere lifestyle and his long hours of prayer.

In 1991 he left for home holidays. “I have the key to my room in Rongai in my pocket. I have left all my belongings there, as I plan to go back in three months. They are expecting me. Everyone must know this. I hope none has the crazy idea to lengthen my stay in Italy with the excuse that I am old.”

While he was in Recoaro, he received a letter from his provincial superior, Fr. Santiago, who invited him to remain in Italy “as some of his confreres objected to his language and his jokes”. “After 57 years in Africa, they tell me this. I know I have sinned, but I can’t accept such a decision. You can’t accuse me at a distance, without giving me a chance to defend myself. The wound inflicted by this backstabbing is taking a long time to heal”, he wrote with much bitterness.

His old friend, Fr. Marengoni welcomed him once again and Fr. Lino returned to Kenya, not to Ngong Road (the Provincial House) but to Rongai with the Apostles of Jesus.

This old missionary, aware of his limits, but animated by a sincere humility and a constant desire to perfect himself, wrote his intentions: “Today in the feast of Saint Martha, 29 July 1991, I have asked the Lord to help me put into practice the following resolutions:

1. I will be hospitable so as to welcome Jesus in others.

2. I will serve my neighbour in need as if he were Jesus.

3. I will do my best with an open heart and mind.

4. I will welcome guests as if they were Jesus coming to rest in my home.

The attitude of this elderly priest, who was almost too lively for his age but still searching to follow the Lord’s will, was truly moving.

Three more years passed and it was 1994, the year of Fr. Lino’s 60th anniversary of priestly ordination. He was expected in his hometown for a great celebration. The new provincial superior of Kenya, Fr. Fernando Colombo, sent him to Italy: “Fr. Lino is expected to stay in Italy for 3 months. He doesn’t need any medical treatment as he is well”, he wrote.

After the celebration, Fr. Lino returned to Rongai and stayed there another year. His sister, Luigina, visited him again. Then Fr. Lino wrote to the provincial superior that he was willing to return to the provincial house “where he would do as much as possible for someone of his age. I am at your total disposal and I am sure of doing the Lord’s will.” The Lord was preparing him to leave Africa for good. In 1996, he had to be urgently admitted to hospital, because he had become “almost paralysed” wrote Fr. Colombo. The hospital staff suggested that he return to Italy and this time he did not oppose it.

At his farewell Mass in the chapel of the provincialate he said: “I want to be buried in Africa”. He was sure that after his recovery he would return to Africa once again.

He reached Rome on Thursday 18 April, accompanied by Bro. Cesaro and Fr. Pasinetti. He was sent to Verona where he felt “at home” and he recovered fairly well.

A year later he wrote to Fr. Milani: “I am asking to be assigned to the Italian province. I willingly accept to be sent to one of our communities even though, for the time being, I prefer to remain in Verona, where I have been welcomed and warmly cared for.”

In his last years, he continually prayed and lived for the missions, so much so that his confreres remarked: “He suffered his purgatory in Italy.”

A particular personality

Fr. Spagnolo is one of those few priests of the Comboni Missionaries who was never a superior, not even for a day. He never cared to be one. In the contrary, he never wanted to attract attention. He lived his work as a teacher and as a secretary to Mgr. Mazzoldi and he willingly left making decisions to others.

Fr. Lino was very shy and this was a source of suffering for him and incomprehension on the part of others. When a tired and hungry confrere arrived at the mission, he would not welcome him, but hide. And if he had to meet him, he was capable of asking: “What did you come here for?” which would make the guest feel uncomfortable. But what was especially touching was to see this elderly priest later approach the guest with tears in his eyes and ask pardon for his rudeness.

This weakness, which later revealed his humility, caused him suffering and confusion and many times brought tears to his eyes.

He died in Verona on 22 August 2000 and was buried in his hometown. The new provincial superior of Kenya during the homily at his funeral said: “This man has presented himself to God’s judgment with his hands full of merits. He trusted Africans very much; he gave his life for them and for the Church in Africa.”

The principal qualities of Fr. Lino were constant serenity, even in difficult situations and which was influenced by a strong faith and a willingness to serve that he showed when he carried out, with seriousness and hard work, what was assigned to him by his superiors. May he intercede from heaven for the Church of Sudan, Uganda and Kenya.