Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

We read today the last part of Mark’s Chapter one, which we have been reading from the third Sunday to this sixth Sunday of ordinary time. (...)

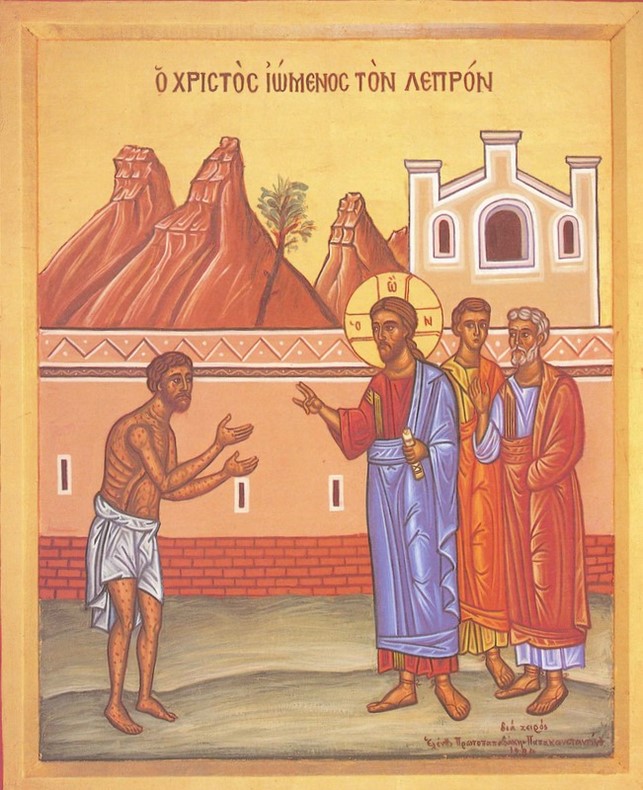

The outstretched hand: God’s power

A commentary on Mc 1, 40-45

We read today the last part of Mark’s Chapter one, which we have been reading from the third Sunday to this sixth Sunday of ordinary time. On reflecting on this reading, that tells us about the experience of a leper healed by Jesus, after his private prayer, I would like to stress four points:

To acknowledge our own weaknesses and to reach out for help

The first thing that calls my attention in this story is that the leper –with a sickness considered at his time grave and a public disgrace– does not hide his reality; on the contrary, he acknowledges his sickness and his need to be helped out. He does not close himself up in bitter lowliness and despair; he comes out and decides to trust in himself, in his neighbour, in Jesus.

We certainly know that the first step to get healed is to accept that we are sick, not to deceive ourselves denying reality in sheer pride. The second step is to accept that we, by ourselves alone, are not able to overcome sickness or an addiction that is enslavering us, or any other situation of conflict. In our time, there’s much talk about self-esteem and self-help… That’s OK: each one of us, as a child of God, has his/her own dignity, talents, and resources…

But my experience is that self-esteem and self-help are not enough. In some moments, one has to know how to ask for help, how to reach out to somebody else, who can give us a needed material help, a good and clarifying word, a moral push… In that line we can understand the prayer of petition, that only the poor and humble understand. The rich and proud ones, of any type, do not ask for anything; they just command or pretend to. But if somebody considers himself/herself always rich, he or she is just lying, hiding his true reality. The leper’s prayer is typical of a humble person: “Lord, if you wish, you can heal me”.

The out stretched hand: God’s power

Confronted with the sincere leper’s prayer –a prayer made with the heart and the entire life, more than with words– Jesus stretches out his hand and touches him. “To stretch out the hand”, over situations and people, is a gesture that in the Bible is related to God’s saving power. It is done by Moses over the Red Sea, by the prophets over their disciples and heirs, by the Apostles over sick people and their successors. But we know that the real power of God is his love. Indeed, as Pope Benedict the XVIth said, “only love redeems”. Love as a gentle pat, love as an encouraging gesture, love as a bandage over a wound, love as a clear word, love as understanding and solidarity in its many ways.

In Jesus, this healing love of God becomes a concrete face, a look that encourages, a hand that touches and heals. Also the Church –community of missionary disciples, extension of Jesus in Today’s history– becomes an outstretched hand to touch the sick, the feeble, the humiliated… a hand that touches and accompanies the voice that says: Do not be afraid, courage, “be healed”. Certainly, sickness is a part of every human experience, a part that cannot be avoided, but the worst of it is the feeling of being valueless, a kind of “nobody”, a useless individual. It is there that the hand of Jesus, the hand of the Church, in the name of Jesus, touches sus and says: Do not be afraid, your are most valuable in the eyes of God, your Father.

To be re-integrated into community’s life

Jesus commands the healed leper to go and present himself to the community leaders and perform the necessary rites to his re-integration. Those rites are quite simple –and we could disagree on its isolated worth– but together they help to keep the community united.

I remember, from my times as a missionary in Ghana, when a lady accused of sorcery was taken to me. After performing some rites and a long dialogue with the community, I went with her to the place where she was living. There I realized what the real problem was: she was a kind of a “leper”, in the sense that she was isolated from the community in so many ways. So the solution was somehow to “push” her to re-incorporate into the community’s life: feasts, rites, works, joys, sorrows, even fights.

Many of us need from time to time an spiritual push to humbly re-integrate ourselves again into our community: family, group, Christian community, parish, Church. To achieve this we need Jesus hand and word, which we can have in many places, especially in the Eucharist.

The messianic secret

Jesus commands the leper to keep silence on what has happened. He is enforcing the famous “messianic secret” to, according to the experts, protect himself from a false (political or triumphalist) interpretation of his mission.

I think that in our times, quite often, we are too much worried about our presence in the Means of Social Communication. Jesus shows us another way: the way of authenticity, of truth an transparency. If then the Media spread the news, we shall see how to react, but to look for publicity at any cost… does not seem to be the Jesus’ method.

Fr. Antonio Villarino, mccj

Sixth Sunday in Ordinary time (B)

Gospel: Mark 1:40-45

A leper came to Jesus and pleaded on his knees: ‘If you want to’ he said ‘you can cure me.’ Feeling sorry for him, Jesus stretched out his hand and touched him. ‘Of course I want to!’ he said. ‘Be cured!’ And the leprosy left him at once and he was cured. Jesus immediately sent him away and sternly ordered him, ‘Mind you say nothing to anyone, but go and show yourself to the priest, and make the offering for your healing prescribed by Moses as evidence of your recovery.’ The man went away, but then started talking about it freely and telling the story everywhere, so that Jesus could no longer go openly into any town, but had to stay outside in places where nobody lived. Even so, people from all around would come to him.

They believed to have locked God in a camp

Fernando Armellini

In Jesus’ time curing a leper was equivalent to raising the dead. The priests could only “declare pure” a leper, not “make him pure.” They are not able to cure him because the healing of leprosy was reserved to God (2 K 5:7).

Inspired by some oracles of Isaiah (Is 35:5f; 61:1), the rabbis had compiled a list of signs of the presence of the kingdom of God. Jesus knew it. In fact he cites it to the envoys of the Baptist: “Go back and report to John what you hear and see: the blind see, the lame walk, the lepers are made clean, the deaf hear, the dead are brought back to life and the good news is reaching the poor” (Mt 11:5). The healing of a leper was therefore much more than a prodigious gesture. It was the proof that the messiah has arrived in the world.

The first part of today’s Gospel (vv. 40-42) reports the fact. A leper, in contravention of the provisions of the law, approaches Jesus and begs him on his knees to be “purified”. He is not asking for healing, but to be purified, that is to be put in a condition to go back into the community. More than the disease itself, what troubled him was the fact of being excluded from civil and religious society.

In front of his request Jesus is moved, stretches out his hand, touches and heals.

Every detail of the story has a meaning and a message.

There is first of all the physical contact with the leper. Jesus lets himself be approached and he touches him. It is not just a benevolent and tender gesture to a person in need of comfort, but it is the reversal of the concept of God. In Jesus the Lord does not appear as the Pharisees imagined: holy, separated from the impure. He accepts the lepers and caresses them because in every man, even one who has fallen into the deepest abyss of guilt, he sees a supremely lovable son.

At the beginning of his public life, at the time of John’s baptism, Jesus has already shown to be perfectly at home alongside the impure people. Later he never moved away from tax collectors, sinners, who had made poor choices. He has never been afraid of being contaminated by them. In fact it was he who communicate to these people his strength of life. Light is always stronger than darkness: if you open the window of a lighted room, it is not the darkness that comes in, but the light that comes out.

How come Jesus assumes an attitude so provocative against the law which prohibited to approach lepers? What is it that drives him to violate the rule requiring exclusion? The evangelist reveals it: he had compassion. Matthew and Luke, who also tell the same episode, omit this detail. Only Mark shows that, faced with the humiliating condition of the leper, he was moved with pity (v. 41). It is this very human feeling that leads to ignore any scheme and custom which do not favor the good of man. The message is clear: in the face of calls for help, the disciple, like the Master, always listens to the heart.

The second part of the passage (vv. 43-45) presents some difficulties of interpretation. How come Jesus sternly warns the leper? Why send him away in an apparently abrupt manner? Is it because before forbidding him to spread the news and then ordering him to present himself to the priests he wants them to see the healing? The two commands seem contradictory. In what sense, the cured leper may be a witness for the priests (v. 44)? The leper did not obey; he begins to spread the news and we are not told if he went or not to the priests. How come Jesus leaves and chooses deserts as dwelling places? Many people were looking for him, and therefore it would be more logical for him to be in a more accessible place.

We begin to understand the meaning of the prohibition to disclose the news of the healing.

For many years the people of Israel expected the Messiah. The prophets—we observed—had shown signs of his presence, and among them there was the cleansing of the lepers. Jesus did not want anyone to know about who had done any of these signs. It would become clear to everyone that he was the awaited Messiah.

This identification would certainly be desirable, but as long as it was clear to all of which the Messiah it was about: not a winner, but a loser, not a ruler, but a servant of all. The people, however, was convinced that the Messiah would be a glorious king as Solomon, a warrior capable and lucky as David, a man of God who would have achieved sensational wonders, even to bring down fire from heaven, like Elijah. Jesus considered these images of messiah diabolical temptations, for this he did not accept they talked of him as the “Messiah of God” before the events of Easter, before having shown to which path the Lord leads people to life. Until then everything had to remain secret, to avoid the misinterpretation of the Father’s plan.

If the fact must remain hidden, why is the leper ordered to present himself to the priests as a testimony to them?

The leper was considered a dead man. Leprosy was “the eldest daughter of the dead” (Job 18:13). In the Old Testament only two great prophets had managed to cure it: Moses had cured his sister Miriam (Nm 12) and Elisha cured the General of Syria, Naaman (2 K 5). To avoid misunderstandings, Jesus does not want the news from spreading among the people; the religious leaders instead, priests must know that a great prophet has arisen in Israel, that God has visited his people and that the kingdom of God has begun. The healed leper must testify to them that the liberation has begun.

Also the fact that the leper run to disclose what Jesus has done for him has a meaning. Mark writes this story after the death and resurrection of Jesus and the veil on the identity of the “Messiah of God” has already fallen. Now it is time to proclaim to everyone that Jesus is the messiah. Who is entrusted with this task?

Here is the answer of the Evangelist: to those who have experienced the salvation obtained in encountering Jesus. In Mark’s Gospel only two people undertake this mission: the leper we are talking about and the man possessed by “demons” who ended up first in the pigs and then in the sea (Mk 5:19-20).

The message is now clear: only those who have tasted the joy of a new life, only those who were marginalized and made the experience of liberation are able to explain to others the wonders that the word of Christ can work.

The last detail: Jesus could no longer openly enter any town, but stayed in the rural areas, in desert places, and people came to him from everywhere (v. 45). This was introduced by the evangelist to highlight an exchange of residence: first the leper who lived far away and could not enter the villages, now it is Jesus who has chosen to live in the condition of the lepers. He has thus shown his desire to share the fate of all those people considered “lepers”.

The passage concludes with the observation: people came to Jesus from everywhere (v. 43). All drew near to him with confidence, because he had chosen the lepers, the last, those who were rejected. These are the people who, even today, instinctively should approach the Christian community, sure to be welcomed with gentleness and love.

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com

He touched him and said: “I do will it. Be made clean”

Mark 1:40-45

Lectio

Mark’s chapter 1 and the first section of Ordinary time each end with another sign of Jesus’ authority over sickness and the power of evil. To be more precise, the cleansing of the leper is the last of a series of Jesus’ transgressions. Since he arrived in Capernaum, Jesus violated the holy time of Sabbath on several occasions: he “worked” the miracle of casting an unclean spirit from a man and curing Simon’s mother-in-law (and enabling her to wait on them!). He also became unclean by the very act of touching a sick woman. That was enough to discredit Jesus in the eyes of the scribes, Pharisees and priests. But Jesus takes a step further. Today’s passage from Mark puts together a number of details that should exclude him from the world of the “pure,” those who observe and obey every commandment and statute of the Law.

Regardless of the content of passages like these in which we find a provocative breaking of the rules (in fact, of the Law with a capital L), there is a tonality, some kind of musical key, which determines the way in which these sayings and actions of Jesus must be understood and interpreted: that is, as paradox. Mark seems to insist throughout his Gospel (as do the other Evangelists, especially John) in setting before the reader apparent contradictions that underline once and again that God’s ways are not the ways humans normally follow. Today’s text, together with the rest of the readings, can be both a model and a guideline to grasp the spirit that pervades and shapes Jesus’ preaching and his proclamation of the Kingdom of God.

There is no need to insist on the double dimension that the Hebrew mentality found in disease: for them it was both physical and spiritual. Leprosy (whatever skin disease this may refer to) is the example par excellence. The text from Leviticus we read today sums up those elements: the fear of contagion (both moral and physical); the rejection the people showed towards lepers; and the feeling of carrying a stigma on their shoulders. The social abandonment and isolation lepers suffered was a burden they had to bear as a punishment all their lives. In a sense, they were “living corpses.” Psalm 102 could express their mood: they were not only “just skin and bones” but felt like “an owl among the ruins” or “a lone sparrow on the roof.” (Curiously, this text has been traditionally applied to the suffering Jesus in his passion).

Here we have some of the paradoxes we will see. In his encounter with Jesus, the impure leper breaks the Law by approaching another person, but in that illegal way he becomes clean and can return to normal life and enter the villages; whereas Jesus, the Saviour who has also transgressed the norms by touching the leper in order to cleanse him, becomes himself impure and, from that moment on, “it was impossible for him to enter the villages openly.” We can also see the contrast existing between Jesus’ authority and that of the priests. The only thing the priests can do is to “declare” the leper clean or unclean, whereas Jesus cleanses and purify him. Another fact to take into account: neither the leper nor Jesus uses the terms “curing” or “healing,” but “making clean.” A last detail: such as it happened in the case of the man with an unclean spirit (1:23-25) or the demons he had driven out of him (1:34), Jesus commands the leper not to tell anything to anyone about his cleaning. That “Messianic secret” could be a sign of his fear of being misinterpreted by the people, who might not understand the kind of Messiah he came to be. This is another paradox we will find again later on.

Meditatio

As usual, a double look at our environment and at our inner self. Nowadays, people do not link disease with sin or guilt, as our conception of reality is quite far from what it was in Jesus’ time. If we exclude some outbreak of fanaticism in the early days of the AIDS epidemic, we are far from seeing disease as a consequence of sin. However, we do have our lepers around us. In fact, we create them whenever we isolate, discriminate or avoid others on grounds as simple as unorthodox religious trends (we decide what is orthodox); political or ideological correctness (the media, including many serious publications, set the criteria for us to follow); social or economic status; race, gender or sexual orientation; age, nationality, or marital status … the list has no end. We seem to need people who are different, “the others,” to be able to exclude them as impure, and so feel secure in our cleanness. We call ourselves Christians, for whom there should be no Jew or Gentile, no slave or free, male or female, but, when, why and how did we lose our “catholic,” “universal” spirit? To which lepers and in what ways can we stretch out our hands and communicate Jesus’ saving and purifying message? Which risks of being considered impure do we dare take in the task of being ministers of mercy? What type of leper/impure person would we invite to our table?

Oratio

A twofold prayer today: for those who feel and are rejected, discriminated against or excluded: that they may feel accepted in our Christian communities. And for us who so often create barriers of distance and isolation: that we may become signs of Jesus’ mercy, compassion and brotherly acceptance.

Contemplatio

Even if this seems to be out place, let me remind you that in a couple of days we will celebrate Ash Wednesday. In todays’ Lectio we have meditated upon and prayed about Jesus’ compassionate sign that restored the unclean leper to a life of wholeness and reconciliation. Lent is a period of conversion. No more than two months have passed since Christmas and, let us admit it, the revival of our Christian life after contemplating the new-born Messiah has already suffered a certain decay. Lent invites us to renew our style of Christian life by means of three traditional spiritual exercises: alms giving, prayer and fasting. I invite you to read Matthew 6:1-6, 16-18, the text for the Mass of Ash Wednesday, and see how you can prepare yourself for your Lenten adjustment and “tune-up” prior to Easter.

Reflections written by Rev. Fr. Mariano Perrón,

Roman Catholic priest, Archdiocese of Madrid, Spain

http://www.americanbible.org

HOMILY

Both the first and the third readings of today speak of something that generated terror in the ancient world: leprosy. Leprosy was a kind generic word that covered a whole range of diseases, specially skin diseases, and most of all contagious and incurable diseases. As a reaction to that horror men felt in themselves, they ostracized and separated the victims of those types of illness, often with religious laws, not only to protect themselves physically from the contagion, but also, obviously, to protect themselves, psychologically, from looking into themselves.

One of the great novels of our century, which won a Nobel prize of literature to its author, is The Plague by Camus, publish shortly after WWII. It is a French novel, but has been translated in English, and I am sure many of you have read it. It is the story of a town in Algeria where the population is suddenly struck by an epidemic of bubonic plague; a plague that a various time in history, before the discovery of vaccines, has decimated large segments of the population of the world. The town is put in quarantine, and the whole book is the description of the attitude of a certain number of characters, as they are confronted with that unexpected physical evil. I think that anyone who wants to reflect seriously about modern contagious illness like AIDS, for example, should read that book.

Camus is not Christian, although in his youth he wrote a doctoral thesis on St. Augustine. He is not an atheist however. He considers himself as post‑Christian. And because of his very honest questioning of the Christianity as he knew it in its reaction to evil, he rediscovers and conveys truths and attitudes that are in fact at times profoundly Christian.

The book is a modern myth about the destiny of man, about what Hopkins called “the death dance in our blood”. For Camus, this “death dance,” this hidden propensity to pestilence, is something more than mere mortality. It is the willful negation of life… the human instinct to dominate and to destroy ‑‑ to seek one’s own happiness by destroying the happiness of others, to build one’s security on power and, by extension, to justify evil use of that power in terms of “history”, of “common good”, or “national security”, or, worst, of “the justice of God”.

There are two main characters in the novel. A priest and a doctor. The physician, doctor Rieux, is the first one to discover the signs of the Plague; and it takes him time before he can convince all the others of what is obvious. All the years that the Plague last in the city, he will devote himself entirely, to taking care of the sick, organizing sanitation, burying the dead, inventing a vaccine, and finally bringing the epidemic to an end. And all of that is considered by him and by Camus, not as something virtuous or heroic in any way. It is just what he had to do in the situation where he was. You don’t praise a teacher for teaching that two and two makes four, he says. If someone is in need and you can do something for him; you just have to do it. There is nothing special in that, even if you risk your life, even if you die. After all, says Camus, there always comes a time in life where those who say that two and two makes four are put to death.

The history of the priest is interesting. At the beginning, he has all the answers. The city has been hit by the Plague because this is what people deserve. God is disappointed with the modern world in general and with them in particular. But in his mercy God is giving the city another chance. The Plague lights the path to future salvation. He can see God in action unfailingly transforming evil into good. Doing so, he “justifies” the plague and tries to make people love their sufferings. To what the good practical doctor, who is not much of a practicing Catholic says, with a lot of Christian compassion: “Christians sometimes talk like that without really thinking it” and he adds that devastating compliment: “They are better than they seem, though”. And he adds that the good Father speaks like this because he has learn only from his theology books. “That’s why he can talk with such assurance of the truth with a capital T. Every country priest… who has heard a man gasping for breath on his deathbed thinks as I do, says the good doctor. He’d try to relive human suffering before trying to point out its excellence.”

In fact, the priest, after seeing a child die in atrocious pain, will come to some of that compassion in the end.

Now, if we come back quickly to our Gospel, I don’t think I need to make a long commentary. It’s obvious that the attitude of the priest at the beginning of the novel, with all his explanations about sin and punishment by God, was the attitude of the Scribes and Pharisees, and in general of the official religion of Israel. The attitude of the doctor in the novel is the attitude of Christ, who never, in the whole Gospel, gives a word of explanation about leprosy or any other illness. He simply touches the leper with his own hand and heals him.

And I suppose the question each one of us has to answer in his own heart is: On what side are we?

http://www.scourmont.be