Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

All the evangelists devote so much space to the passion and death of Jesus. The facts are basically the same, though narrated in different ways and with diverse perspectives. Each evangelist then puts in the story episodes, details, underscores that are his own and which show the care and concern for some themes of catechesis, considered significant and urgent for their communities. (...)

Gospel Reflection

Mark 14:1—15:47

All the evangelists devote so much space to the passion and death of Jesus. The facts are basically the same, though narrated in different ways and with diverse perspectives. Each evangelist then puts in the story episodes, details, underscores that are his own and which show the care and concern for some themes of catechesis, considered significant and urgent for their communities.

Today’s version of the story of the passion being proposed to us is that of Mark. In our commentary we will only highlight the specific aspects.

A first important element is the lack of response of Jesus to the kiss of Judas and to the violent act committed by one of those present (Mk 14:46-49).

While the other Evangelists relate a few words of the Master to Judas, “Judas, with a kiss do you betray the Son of Man?” (Lk 22:48) and to Peter: “Put your sword back into its place!” (Mt 26:52), Mark presents Jesus not rebelling against the events that he cannot impede, almost passively accepting what is happening to him and that, in the end, he concludes: “But let the Scriptures be fulfilled” (Mk 14:49).

The evangelist portrays a meek and helpless Jesus, who gives himself in the hands of the enemies, without reacting. He stresses this fact to support the faith of the Christians of his community, severely tried by persecution. In his Son, the Father has not reserved a preferential treatment. He has not spared him from the injustices, betrayals and the dramas that affect people. Like him, the disciples will have to deal with deceit, hypocrisy, pretense, violence. This is the fate of the righteous, often intended to be a victim of the malice of the wicked, as announced in the Scriptures (Ps 37:14; 71:11). In Mark, Jesus considers not worth a word of disapproval the senseless and agitating act of Peter: his putting hand on the sword is so far from the evangelical principles and do not even deserve to be taken into account.

The disciple who, like Peter, believes to be able to address the injustices through violence, in fact only complicates the situations and then has to escape… Those who use violence stray from the Master and plunges into the darkness of the night.

All the evangelists tell us that the disciples, as soon as they realized that Jesus did not respond, fight, nor invited them to fight, fled. Only Mark recalls a curious detail: “A young man covered by nothing but a linen cloth, followed Jesus. As they took hold of him, he left the cloth in their hands and fled away naked” (Mk 14:51-52).

The detail is really marginal and perhaps it was inserted by the evangelist as an autobiographical feature: the tradition, in fact, has identified that boy as Mark himself.

However, the little “comic scene of the young man who fled naked” reproduces, in the evangelist’s intention, the nonchalant behavior of many Christians who easily fall short of their commitments. To follow the Master, the apostles have abandoned all (Mk 10:28), now, when they realize that the goal of the trip is the gift of life, they left everything. This time, however, is not to follow the Master, but to escape. This is what happens—Mark insinuates—even to Christians: sometimes called to deal in an evangelical way with the opposition of life, to avoid risks, they leave the baptismal garment that identifies them and renounce the courageous choices that their faith requires.

All evangelists indicate that, after an initial enthusiastic reception, the crowds gradually broke away from Jesus who in the end was left alone with the twelve. These, in turn, in the moment of decisive choice, fled. None but Mark, however, puts emphasis on the loneliness of Christ during passion. Reading the other gospels, there is always someone who is on the side of Jesus or takes position in his favor: an angel in Gethsemane (Luke 22:43), a disciple or Pilate’s wife in the process (Jn 18:15; Mt 27:19), a great crowd and a group of women on the way to Calvary (Luke 23:27-31); his mother, the favorite disciple, some friends, the good thief (Jn 19:25; Lk 23:40).

In Mark, there’s just no one. Jesus is betrayed by the crowd that prefers Barabbas. He is mocked, beaten and humiliated by soldiers; is insulted by passers-by and the leaders of the people present at the moment of his crucifixion. Darkness was around him. Only at the end, after his death has been told, it was noted: “There were also some women watching from a distance” (Mk 15:40-41).

Completely alone, Jesus experienced the anguish of one who, being certainly committed to the just cause, feels defeated. His cry, “My God, my God, why have you deserted me” (Mk 15:34) seems outrageous, but expresses his inner drama. At the time of his death, he had the experience of impotence, of failure in the fight against injustice, falsehood, oppression exerted by religious and political power.

One who commits himself to live coherently his faith—it is the message of Mark to the Christians of his community—must take into account that, at the crucial moment, he will be left alone. He will be betrayed by his friends and refused by his own family, feeling oneself abandoned by God and wondering if it was worth to suffer so much to find oneself defeated. In these moments he will launch his cry to the Father, but, to avoid falling into the abyss of despair, he will cry out with Jesus. Only then he will receive an answer to his anguished questions.

Another feature of Mark’s story is the insistence on the very human reactions of Jesus in the face of death. Only Mark notes that Jesus, in the Garden of Olives, realizing that they were looking for him to put him to death, “he became filled with fear and distress” (Mk 14:33). The other evangelists avoid to present to us a fearful Jesus, as if shaken by a terror that, only with difficulty, he was able to control.

History is full of heroes who faced death with serenity and disregard for the suffering. Jesus is not among these people. He cried, he was afraid, he looked for someone who would understand and be near him in the moment of the most dramatic choice of his life.

It is comforting that the facts are just as Mark told them: contemplating this Jesus man, not superman, our companion in suffering. He experienced, as we do, how hard and difficult it is to obey the Father. We feel encouraged to follow him.

In the passion narrative of Mark, Jesus is always silent. To the religious authorities who ask him if he is the Messiah and to Pilate who wants to know if he is king, he simply replies: “I am” (Mk 14:62; 15:2). That’s it. During the trial, not a word came out from his mouth. In the face of insults, provocations, lies, he is silent; he makes no reply (Mk 14:61; 15:4-5). He knows that those who want to condemn are conscious of his innocence. He is aware that his enemies have already decreed his death and that it is not worth to lower oneself to their level, accepting an argument that would not change anything.

There is a silence that is a sign of weakness and lack of courage: that of those who do not take action to denounce injustices because they are afraid of losing friends, getting themselves into some kind of trouble or antagonize the people who count. Instead, there is a silence that is a sign of strength of character: that of someone who does not react to provocation, does not lose heart in the face of arrogance, insult, slander. It is the noble silence of those who are convinced of their own righteousness and loyalty and are certain that the just cause for which they are battling will eventually triumph.

The Christian is not a coward who is resigned, does not battle against evil. He is one who seeks to establish the truth and justice, but he is also the one who, like the Master, has the strength to be silent, refusing to resort to unfair means employed by his opponents: the calumny, lies, violence. He does not fear defeat, and does not care about the victory of his enemies: he knows that their triumph is short-lived.

Only Mark, referring to Jesus’ prayer to the Father, shows the Aramaic name that he used “Abba, Father” (Mk 14:36).

“Abba” corresponds to one of the many terms that, here too, the children use to speak to their parents. The rabbis said: When a child begins to taste the wheat (i.e., when it is weaned), it learns to say “abba” (daddy) and “imma” (mother). The adults avoided this childish term, but resumed using it when the father grew old, when he became a grandfather, he needed assistance and most affection. Abba therefore expressed confidence and tenderness.

In the gospels, this term appears only here. Jesus uses it in the most dramatic moment of his life, when, after asking the Father to spare him a so hard a trial, he leaves himself with confidence in his hands.

It is an invitation to never doubt, even in the seemingly most absurd situations, God’s love and to always remember that he is Abba.

The climax of the whole story of the Passion of Jesus according to Mark is the profession of faith of the centurion at the foot of the cross: “The captain, who was standing in front of him, saw how Jesus died and heard the cry he gave; and he said, ‘Truly this man was the Son of God.’” (Mk 15:39).

Since the beginning of the Gospel of Mark, the crowds and the disciples wonder about Jesus; they are asking who he is (Mk 1:27; 4:41; 6:2-3,14-15). But no one can grasp his true identity. When someone proclaims him the messiah, he immediately, takes action to impose silence (Mk 1:44; 3:12): his identity must not be revealed; the secret must be kept until the end, because only after his death and resurrection it will be possible to understand who he really is.

Now, what is surprising is the discovery and the proclamation of Jesus “Son of God” are not made by one of the apostles or by a disciple, but by a pagan. It’s in the mouth of a foreign soldier that the formula is found. It is disconcerting for its purity that the early Christians employed a pagan to proclaim their faith in Christ.

The way that Jesus had died: giving a strong cry, the cry of the righteous spoken of in the book of Psalms (Ps 22:3,6,25) opened the eyes of the centurion. It made him recognize in the condemned the “Son of God,” not the earthquake, the darkening of the sun or some other miracles.

What he was not able to get calming waves of the sea, healing the sick, multiplying the loaves, Jesus now gets it with the gift of life. It is the miracle of his life shaped by love alone that converts the pagan centurion.

In this context, the meaning of the veil of the temple that “was torn in two from top to bottom” (Mk 15:38) becomes clear. This is not an information. There was no miraculous tear of the curtain that served as a partition between the Holy and the Holy of Holies (Ex 26:33), as well as, at the time of the baptism of Jesus, the heaven was not materially opened.

Mark is telling a much greater miracle: a miracle of the spiritual order. At the beginning of his public life the heavens “were torn,” that is, peace and communication between heaven, the abode of God, and the earth, the people’s house, are re-established. Now Jesus’ supreme act of love has brought down all the barriers, also upon earth.

In the Holy of Holies, believed to be the abode of the Lord, only the high priest had access to it once a year, on the solemn day of the feast of atonement for sins. Now every person, whether Jew or pagan, like the centurion, can come and go from the Holy of holies, because it is the house of his Father. God cannot be imagined far away, inaccessible; to him, even the greatest sinner can approach with confidence, knowing oneself his son or daughter.

After the death of Jesus, all the evangelists put into the scene Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the council who went to Pilate for permission to bury the crucified One. Only Mark, however, specifies that his was a courageous gesture (15:43). To declare themselves disciples of Jesus when the crowds cheered him was easy, but to stand as his friend before the authority that had sentenced him to death required great courage.

Joseph of Arimathea is, for Mark, a reminder to those fickle, opportunistic, weak disciples who do not have the courage to profess their faith, who are ashamed of moral values taught by Christ and that, to avoid trouble or just not being laughed at, they easily adapt to the current morality.

Fernando Armellini

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com/

Have among yourselves the same attitude…

Mark 14:1 – 15:47

Lectio

Today’s heading, the first verse from our reading from Philippians, could be the guideline to this first celebration of Holy Week (and, given the extension of today’s Lectio, to the Week as a whole). Jesus’ attitude, announced in the text from Isaiah, is that of self–denial and renouncement: “he emptied himself,” became the suffering servant and willingly fulfilled his Father’s will. Fidelity to God’s designs, expressed by his mature obedience as a free man, is perhaps the trait that best describes Jesus’ attitude during his entire life. Paul, in his introduction to the Christological hymn, invites the Christians from Philippi to have that same attitude in their lives.

The four Gospel accounts of the Passion offer not only the description of the events that happened in the last days of Jesus’ life, but at the same time provide us with a portrait of the people around the rabbi and prophet they had followed, admired, recognized as a man of God, betrayed and abandoned. Those characters may be a mirror where we can see traits of our own personality and attitude in our following of Jesus. If we look in depth, none of them is absolutely evil (not even Judas), and all of them together show a full image of our contradictory human nature. For Paul, no doubt, the community at Philippi, (or any Christian community for that matter), is an image of Christ, his visible body in this world; hence the importance of their behaviour amidst their generation, where they should shine as living lights (2:15).

The first character we find does not seem to play a role in Jesus’ passion, but she and her actions are the best anticipation, and a basic key, to all the events that are about to happen. After his entry into Jerusalem, the cleansing of the Temple and his long disputes with his adversaries, Jesus returns to Bethany. There, in the houses of Simon the Leper, an unidentified woman (not a sinner, not Lazarus’ sister, not the Magdalene) anoints Jesus, and the extravagance of the perfume provokes a scandal among those present, ostensibly worried about the poor. No one seems to grasp the prophetic sign that only Jesus understands and explains: “She has anticipated anointing my body for burial” (14:8). She has also anticipated Jesus’ role as a king and priest that he will enact in his passion. Curiously, her gesture will be remembered, even if we do not know her name. This attitude of silent generosity and devotion will be completed by the words of the Roman centurion: “Truly, this man was the Son of God!” (15:39). A pagan proclaims aloud what Mark had announced in the first line of the Gospel. As usual, a paradox: a woman and a Gentile enclose, as if they were brackets, the mysteries of Jesus’ passion and death.

The disciples deserve special attention. The three who were closest to Jesus, “could not keep watch for an hour” (14:37) when he was “troubled and distressed,” and prayed that the “hour might pass by him” (14:33-35). Even Simon, who had boasted about the firmness of his faith and his willingness “to die with you [him]” (14:29-31), will swear he did not know him (14:66-72). Judas, “one of the Twelve,” as Mark underlines, will betray him (14:10-11) and “will kiss” him as a sign for those who would arrest and “lead him away” (14:43-46). One of the “bystanders” (another disciple, we assume) tried to defend Jesus with a sword (14:47); another, a young man, fled, even if that meant the shame of his nakedness (14:51). But, in the end, they were all so frightened at the event, that “they all left him [Jesus] and fled” (14:50).

As for the authorities, we know too well the role they played. Those belonging to the religious élite, chief priests, Pharisees, scribes, were convinced that Jesus was a real danger to their social and political stability. After recurring to false witnesses to provide evidence and deliver Jesus to Pilate, the Roman governor, Jesus himself gave them the excuse to execute their plans. His words, “I am” (14:62) identifying himself with God, were utter blasphemy and deserved death (14:53-64).

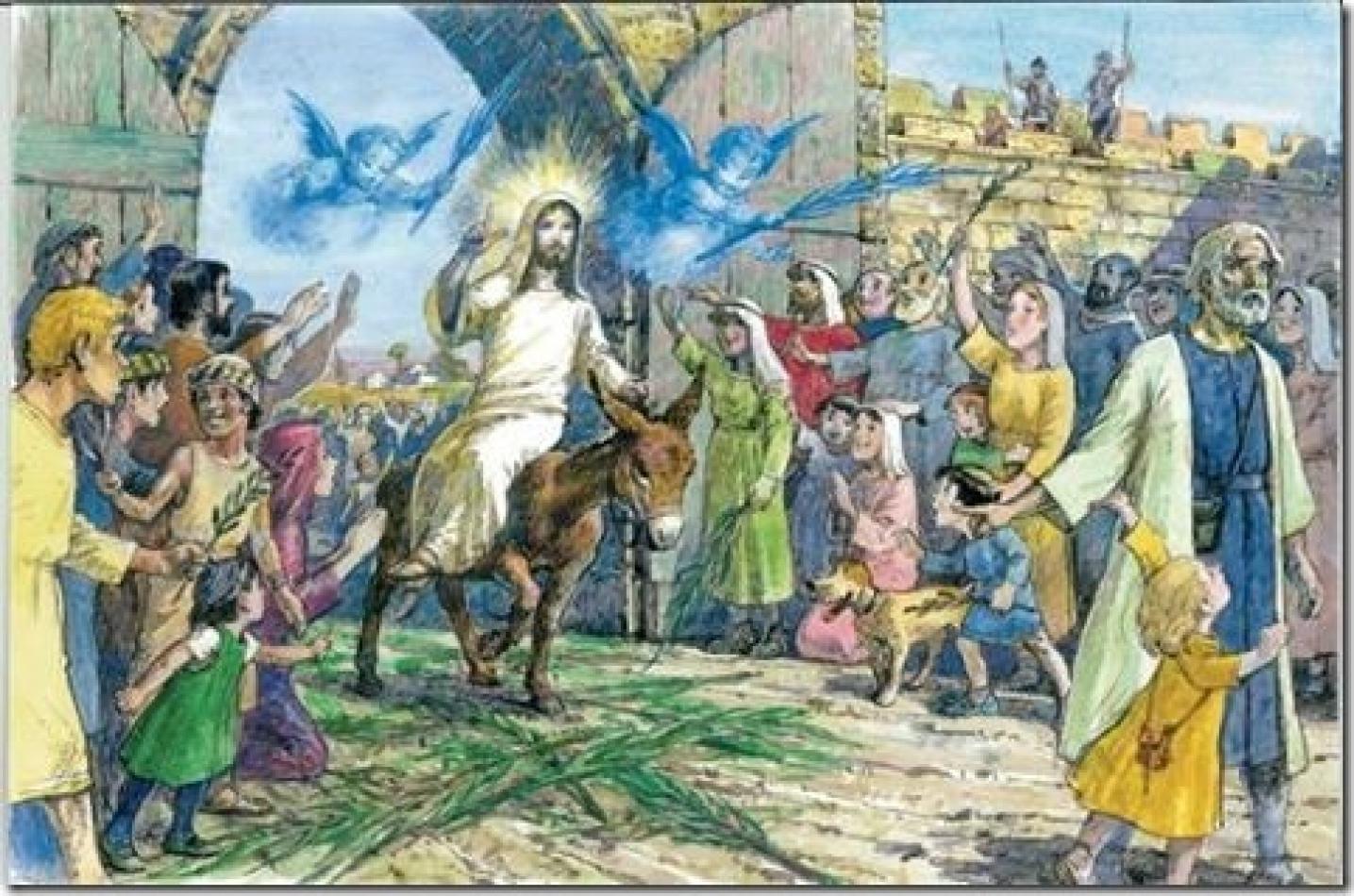

The crowd that had greeted Jesus with hymns, and “spread their cloaks on the road” and “leafy branches” as he advanced riding on a colt, (11:8-10), will shout loudly and ask Pilate to “crucify him” a few days later (15:6-15). Some of them, when they saw him nailed to the cross, “reviled him,” while the chief priests, with the scribes, “mocked him” (15:29-32). Even the bandits crucified with Jesus insulted him (15:32).

The Roman characters play the roles we would expect in such circumstances. Pilate did not want to have problems with a rebellious crowd. Jerusalem was packed with people who had come for the Passover celebration, and they were, as we have seen, easily aroused and manipulated, so after a lukewarm attempt to exchange Jesus for Barabbas, (although he knew the crooked reasons invoked by the authorities), Pilate decided “to satisfy the crowd” and “handed him [Jesus] to be crucified” (15:1-15). As for the Roman soldiers, the cruelty of their actions reflect, unfortunately, their common practice with prisoners.

There are, still, two groups of people near Jesus. He must have been very weak, for they recurred to a passer-by, Simon, to carry the cross (15:21). Although he was forced to perform that task (the authorities could demand that type of service), and we have no hint about his religious feelings, Simon plays a deep symbolic role. His action recalls the two main conditions Jesus had posed to anyone who “wished to come after him,” that is, to denying himself and take up his cross (8:34). When reading or listening to this passage, persecuted Christians of the time must have had a clear understanding of what Jesus meant.

The women, not only those identified by name (Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of the younger James and Joses, and Salome), but the group of those who had followed him to Jerusalem, are there and, although they remained at a distance, they did not abandon him (15:40-41). That is why they will be the first witnesses to the resurrection.

Only after Jesus’ death, another character will enter the scene, Joseph of Arimathea, who will take care of his body and bury him (15:42-47). Just a linen cloth was used, no anointment or perfume, for Jesus had already been anointed by the unknown woman who would be remembered “wherever the Gospel is proclaimed” (14:9).

Meditatio

To be honest, the reading of the Passion is so rich, that I dare not give any guidelines for our Meditatio. Any approach you adopt can be valid. I humbly suggest comparing the actions of the characters we have seen with parallel feelings Jesus must (or may) have experience in relation to them, and trying to understand in what way he was following his Father’s designs. Or trying to identify yourself with some of those characters to find what you share with them. Or trying to find in your own personal environment circumstances similar to those described in the text: self-sufficiency and pride, treason, selfish interests, hidden fears, ingratitude… and courage and pity, compassion and sympathy, humble generosity and effective action. The list of positive and negative elements is endless. In any case, see in what ways you can get closer to the suffering Jesus who died for us.

Oratio

As I was writing these lines, I heard the news that 21 Egyptian Christians from the Coptic Church have been beheaded on a beach near Tripoli for the simple fact of following Jesus. Let us pray –I know I have urged you to do so several times – for our brothers and sisters who are literally being persecuted because of their faith: that they may be comforted in their own “passion” by Jesus, whose steps they are following. Besides this particular intention, I suggest we should all pray for hope. In a sense, Jesus’ passion and death is a parable of the tormented, suffering existence many human beings undergo in our world. They carry in their bodies and souls the wounds Jesus himself suffered. Let us pray: that we may be conscious of such distress and find the effective means to alleviate them.

Contemplatio

Our first reading today is one of the four songs of the “Suffering Servant” in Isaiah’s book. These hymns are read in the Catholic masses on the following days. Even if you are a regular churchgoer, read those songs, as they can help you prepare for the solemn celebrations: Isaiah 42:1-7; 49:1-7; 50:4-9, and 52:13 – 53:12.

Reflections written by Rev. Fr. Mariano Perrón,

http://www.americanbible.org/resources/lectio-divina

The Passion and Death of Jesus

Mark 14,1 – 15,47

The final defeat as a new call

a) A key to the reading

Generally, when we read the story of the passion and death, we look at Jesus and the suffering he had to endure. But it is worthwhile, at least once, to also look at the disciples and see how they reacted to the cross and how the cross impacted on their lives, for the cross is the measure for comparison!

Mark writes for the communities of the 70’s. Many of these communities, whether in Italy or Syria, were going through their own passion. They were faced with the cross in many ways. They had been persecuted at the time of Nero in the 60’s and many had died devoured by wild beasts. Others had betrayed, denied or abandoned their faith in Jesus, like Peter, Judas and other disciples. Others asked themselves: “Can I bear persecution?” Others were tired after persevering through many trials without any results. Among those who had abandoned their faith, some asked themselves whether it was possible to rejoin the community. They wanted to start their journey again, but did not know if it was possible to rejoin. A cut branch has no roots! They all needed new and strong reasons to restart their journey. They were in need of a renewed experience of the love of God, one that surpassed their human errors. Where could they find this?

For them, as for us, the answer is in chapters 14 to 16 of Mark’s Gospel, which describe the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus, the time of the greatest defeat of the disciples and, in an hidden way, their greatest hope. Let us look into the mirror of these chapters to see how the disciples reacted to the Cross and how Jesus reacts to the infidelity and weaknesses of the disciples. Let us try to discover how Mark encourages the faith of the community and how he describes the one who is truly a disciple of Jesus.

b) Looking into the mirror of the Passion to know how to be a faithful disciple:

The final failure as a new call to be disciple

This is the story of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus seen from the point of view of the disciples. The frequency with which this story speaks of the incomprehension and failure of the disciples, most probably corresponds to a historical fact. But the main interest of the Evangelist is not to tell that which took place in the past, rather he wants to provoke a conversion in the Christians of his time and to arouse in them and us a new hope, capable of overcoming discouragement and death. There are three things that stand out and need to be considered deeply:

- The failure of those chosen: The twelve who were specially called and chosen by Jesus (Mk 3:13-19) and sent in mission by him (Mk 16:7-13), fail. Fail completely. Judas betrays, Peter denies, all run away, no one stays. Total dispersion! Seemingly, there is not much difference between them and the authorities who decree the death of Jesus. Like Peter, they too want to eliminate the cross and want a glorious Messiah, king, blessed son of God. But there is one deep and real difference! The disciples, in spite of all their faults and weaknesses, hold no malice. They do not have any evil intention. They are an almost faithful replica of all of us who walk the way of Jesus, falling all the time but always getting up again!

- Fidelity of those not chosen: As a counterpoint to the failure of some, the strength of faith of others is presented, those who were not part of the chosen twelve: 1. An anonymous woman from Bethania. She accepted Jesus as Messiah Servant and, thus, she anoints him in anticipation of his burial. Jesus praises her. She is a model for all. 2. Simon of Cyrene, father of a family. He is forced by the soldiers to do that which Jesus had asked of the twelve who ran away. He carries the cross behind Jesus to Calvary. 3. The centurion, a pagan. At the moment of death, he makes his profession of faith and recognises the Son of God in the tortured and crucified man, one cursed according to Jewish law. 4. Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James and Salome, “and many other women were there who had come up to Jerusalem with him” (Mk 15:41). They did not abandon Jesus, but determinedly stayed at the foot of the cross and close to the tomb of Jesus. 5. Joseph of Arimathaea, a member of the Sanhedrin, who risked everything by asking for the body of Jesus to bury him. The twelve failed. The continuation of the message of the Kingdom did not pass through them, but through others, particularly the women, who will be given a clear order to go call back those failed men (Mk 16:7). And today, through whom does the message pass on?

- The attitude of Jesus: The manner in which the Gospel of Mark presents the attitude of Jesus during the telling of the passion is meant to give hope even to the most discouraged and failed of the disciples! Because no matter how great the betrayal of the Twelve was, the love of Jesus was always greater! When Jesus announces that the disciples will run away, he already tells them that he will wait for them in Galilee. Even though he knew of the betrayal (Mk 1418), the denial (Mk 14:30) the flight (Mk 14:27), he goes on with the gesture of the Eucharist. And on the morning of Easter, the angel, through the women, sends a message to Peter who had denied him, and to all the others who had fled, that they must go to Galilee. The place where everything had begun is the place where everything will begin again. The failure of the twelve does not bring about a break in the covenant signed and sealed in the blood of Jesus.

c) The model of the disciple: Follow, Service, Go up

Mark emphasises the presence of the women who follow and serve Jesus from the time he was in Galilee and who go up to Jerusalem with him (Mk 15:40-41). Mark uses three words to define the relationship of the women with Jesus: Follow! Serve! Go up! They “followed and looked after” Jesus and together with many other women “went up with him to Jerusalem” (Mk 15:41). These are the three words that define an ideal disciple. They are the models for the other disciples who had fled!

- Follow describes the call of Jesus and the decision to follow him (Mk 1:18). This decision implies leaving everything and running the risk of being killed (Mk 8:34; 10:28).

- Serve says that they are true disciples, for service is the characteristic of the disciple and of Jesus himself (Mk 10:42-45).

- Go up says that they are qualified witnesses of the death and resurrection of Jesus, because as disciples they will go with him from Galilee to Jerusalem (Acts 13:31). Having witnessed the resurrection of Jesus, they will also witness to what they have seen and experienced. It is the experience of our baptism. “So, by our baptism into his death we were buried with him, so that as Christ was raised from the dead by the Father’s glorious power, we too should begin living a new life” (Rm 6:4). Through baptism, we all share in the death and resurrection of Jesus.