Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

Prayer must not be a way to force God to do our will. Why are we invited to turn to him with insistence? What is the meaning of prayer? To these questions, Jesus responds today with a parable (vv. 1-5) and with application to the life of the community (vv. 6-8). The parable starts with the presentation of personages. (...)

Gospel reflection

Luke 18:1-8

Fernando Armellini

Prayer must not be a way to force God to do our will. Why are we invited to turn to him with insistence? What is the meaning of prayer? To these questions, Jesus responds today with a parable (vv. 1-5) and with application to the life of the community (vv. 6-8). The parable starts with the presentation of personages.

The first is the judge whose duty should be that of protecting the weak and the defenseless, instead of being godless and unsympathetic. (v. 2). He himself, in his soliloquy, accepts that the wicked reputation he made of himself has been totally justified: “I neither fear God nor care for about people” (v. 4). Jesus’ description of this man is quite realistic. One would think that it refers to some cases of blatant injustice he has heard or witnessed.

The second personage is the widow. In the Middle Eastern literature and in the Bible she is a symbol of a defenseless person, exposed to abuse; a victim of exactions, who cannot appeal to anyone except to the Lord. Sirach is moved by her condition and threatens anyone who abuses her: “The Lord is judge and shows no partiality. He will not disadvantage the poor, he who hears the prayer of the oppressed. He does not disdain the plea of the orphan, nor the complaint of the widow. When tears flow down her cheeks, is she not crying out against the ones who caused her to weep? Her sorrow obtains God’s favor and her cry reaches the clouds” (Sir 35:12-16).

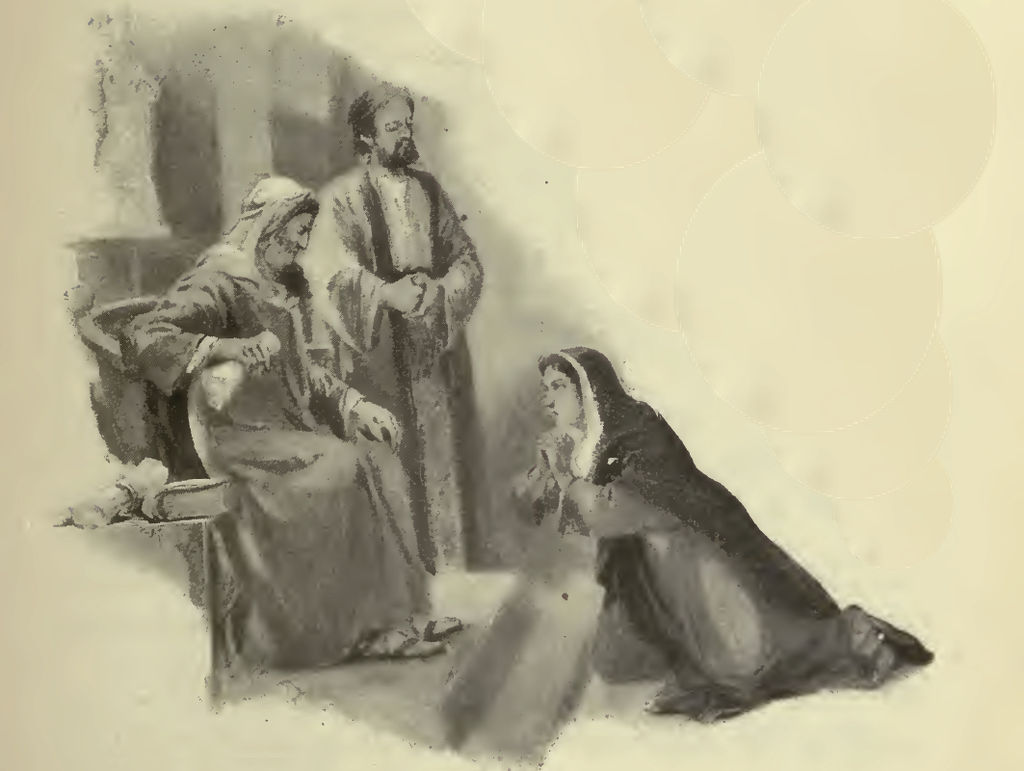

In the parable, a widow who suffered injustice is put to the scene. Perhaps she was deceived in a transition of inheritance or was a victim of a scam. Perhaps someone has exploited her work; certainly, she has been wronged and claims her rights but no one listens to her. She has no money to pay a lawyer nor knows someone who could plead her cause; no one to advise her. She has a single card in hand and plays it: she pesters the judge repeatedly, with obstinacy, at the cost of looking indiscreet (v. 3).

After having presented the two personages, the parable continues with the soliloquy of the judge. One day he decides to solve the case not because he realizes his misbehavior but he is tired and annoyed by the insistence of the woman. He says: this widow is troublesome, she pesters me and becomes unbearable (vv. 4-5).

The parable concludes here. The following verses (vv. 6-8) contain an actualization. We will comment on it later. First, we try to grasp the meaning and the message of the parable.

Who is the unjust judge? The answer seems obvious, and even embarrassing: it’s God! But it is not so. This personage, in reality, is secondary. He is introduced only to create an unsustainable situation that Jesus wants to draw attention to. It is the condition in which the disciples find themselves in this world that is still dominated by evil and profoundly marked by death.

At the time of Jesus, injustice was rampant in oppressive political, social, and religious systems. Today it is represented by abuses and fraudulence at the cost the poorest, by inexplicable and absurd events and practices that disturb and contradict our longing for life.

What do we do in these situations?

Here is the message of the parable: pray. Jesus has told so—says the evangelist—to inculcate the belief that it is necessary to pray always, without ceasing (v. 1).

Prayer is the greatest means in order not to lose one’s head in the most difficult and dramatic moments when everything seems to conspire against us and the Kingdom of God.

How to be always praying? Prayer should not be identified with monotonous repetition of formulae that weaken both, the one who recites it and the one who listens. I believe—even God may be annoyed, if they are not expressions of an authentic sentiment of the heart (cf. Am 5:23). Jesus calls the attention of the disciples not to pray as the pagans who believe it to be heard for their much speaking (Mt 6:7).

True prayer, that which must never be interrupted, consists in maintaining oneself in constant dialogue with the Lord. Dialogue with him makes us evaluate reality, events, and people with their criteria of judgment. We examine with him our thoughts, sentiments, reactions, and plans.

To pray always means not to take some decisions without first consulting him. If, even for a single moment one would interrupt this rapport with God, if—to use the image of the First Reading—the arms are let down, immediately the enemies of life and freedom will take the upper hand. These enemies are called passions, uncontrolled impulses, and instinctive reactions. They create conditions for foolish choices.

It is prayer that allows, for example, to control impatience in wishing to establish the Kingdom of God at all costs and by any means. It is prayer that blocks us to force consciences and teaches us to respect the freedom of each person.

The conclusion of the passage (vv. 6-8) is rather enigmatic. The last phrase: “but when the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on earth?” seems to insinuate the doubt on the final success of Christ’s work. To understand it, it is necessary to verify what he is speaking about and who are listening to him. Then a correction to the translation must be also made.

It is the Lord who talks and the Gospel of Luke indicates that it is the Risen One. He turns to the chosen ones, the persecuted Christians of Luke’s community. He wants to give an answer to their faith dilemma.

We are in the 80s of the first century, when, in Asia Minor, a very violent persecution started. Domitian claims that all should adore him as a god. The pagan religious institutions, servile and flattering, adequately give in and support the maniacal eccentricity of the sovereign. The Christians do not. They cannot—as the Book of Revelation says (Rev 13)—bow before the “beast” (the Domitian divo) and for this, they undergo harassment and discrimination.

Now it’s clear who the widow of the parable is: it is the church of Luke, the church whose Spouse is taken away; it is this community that awaits his coming, even though she may not know the day or the hour of his return and that each day, with insistence, she is pleading: “Come Lord Jesus” (Rev 22:20).

To this invocation, the Lord gives a consoling answer, with a rhetoric question, “And will not God give justice to his chosen ones who day and night cry to him” followed by a peremptory affirmation; Yes, I tell you: He will bring justice to them soon; even if he makes them wait for long.” You may have noted that the question mark at the end of the sentence has been removed in my translation. This alteration makes the meaning of the text more coherent.

A major temptation of Christians is discouragement and distrust in the face of a long wait for the Spouse who delays and tolerates injustice.

The last sentence: “When the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on earth?” does not refer to the end of the world but to the saving arrival of Christ in this world.

Before the inexplicable slowness of the judge, the widow could have resigned and despaired to the fate of not obtaining justice one day. The Lord alerts the community against this danger represented by discouragement and resignation of the thought that the Spouse is not coming any more to render justice. He will surely come, but will he find his chosen ones ready to welcome him? To someone, his slowness could cause a loss of faith!

Fernando Armellini

Italian missionary and biblical scholar

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com