Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

We are at the penultimate Sunday of Ordinary Time and the liturgical year is drawing to a close. The liturgy takes the opportunity to speak to us about the “last things” (éschata in Greek): the end of time, the end of this world, the end of things, the end of our lives… The Word seeks to evangelise our fears and free us both from anguish and from foolish carelessness. It invites us to discernment, to reflect on the purpose and meaning of existence, and to cultivate hope and a positive outlook on life.

“By your perseverance you will save your lives.”

Luke 21:5–19

We are at the penultimate Sunday of Ordinary Time and the liturgical year is drawing to a close. The liturgy takes the opportunity to speak to us about the “last things” (éschata in Greek): the end of time, the end of this world, the end of things, the end of our lives… The Word seeks to evangelise our fears and free us both from anguish and from foolish carelessness. It invites us to discernment, to reflect on the purpose and meaning of existence, and to cultivate hope and a positive outlook on life.

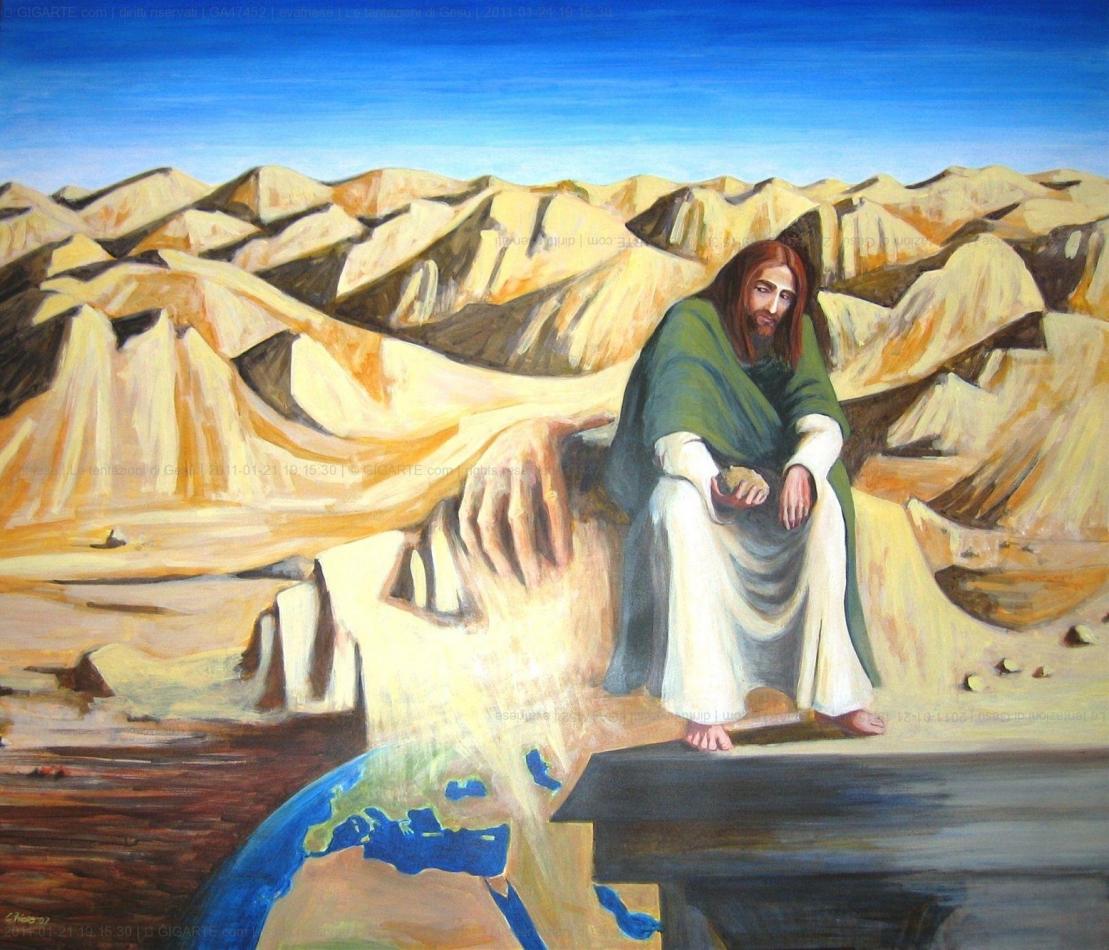

Jesus is nearing the end of his days. Shortly beforehand he had wept at the sight of Jerusalem and foretold its destruction: “They will not leave within you one stone upon another, because you did not recognise the time of your visitation!” Jesus loves his city, just as he loves our “city” today. But—alas—how often he must also say to us, with sadness: “If only you had recognised on this day the things that make for peace!” (Lk 19:42).

The end of the Temple

We find ourselves in the Temple of Jerusalem, rebuilt by Herod the Great, an architectural marvel and the pride of Israel. The esplanade was about 500 metres long and 300 wide, with an area equivalent to 22 football pitches. Work began around 19/20 BC and the entire complex was completed only around AD 63/64, a few years before its destruction by the Romans in AD 70. The Jewish-Roman historian Josephus (AD 37/38–100) reports that 10,000 workers were involved, and 1,000 priests were specially trained as stonemasons and carpenters to work in the sacred areas, where only priests could enter. The Temple was considered the eighth wonder of the world. Its magnificent construction so impressed those who arrived in Jerusalem that it was said: “He who has not seen Jerusalem the radiant has never seen beauty.”

We can imagine the shock and dismay when Jesus prophesied the destruction of the Temple. To the ears and hearts of his listeners, it was truly the “end of the world”.

The destruction of the Temple prompts reflection. It symbolises our own human endeavours: so many years of dreams and plans, work and investment, commitment and sacrifice… suddenly destroyed beyond repair! The magnificent building, completed after eighty years, would soon be razed to the ground. And this happened because the people of God had placed their security in that Temple.

In vain had the prophet Jeremiah warned, centuries earlier—before the exile and before the destruction of Solomon’s Temple: “Do not trust in deceptive words, saying, ‘This is the temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord!’ [Unless you practise justice] I will treat the house upon which my name is invoked, in which you trust… as I treated Shiloh,” the temple of the northern kingdom, destroyed by the Assyrian invasion in 721 BC (cf. Jer 7:1–15). The Temple had become an idol, a false security.

The Church too has often placed its security in its own “temples”: its institutions, social power and influence, traditions and dogmas… rather than in faith in Jesus Christ. For this reason, we too feel disoriented today with the end of “Christendom” and the unprecedented challenges of the future.

And I—where do I place my trust? What is the “temple” in which I confide? Do I feel secure because I go to church, or because I am religious, or because I call myself a Christian?

The end of the world

In the context of the end of Jerusalem and the Temple, the theme of the “end of the world” emerges. Jesus speaks in apocalyptic language, a literary genre that uses very strong symbolic imagery—consider, for example, the Book of Revelation. But its purpose is to instil hope in believers. Indeed, its Greek meaning is “revelation”, the “lifting of the veil” on history so as to understand its meaning.

“When will all this happen?” ask the apostles. Jesus does not give a direct answer. Indeed, elsewhere he says he does not know. Today we might ask Google and even find precise dates. But these concern us little. We are more troubled by the nuclear threat—spoken of increasingly often—and by the climate crisis. In reality, it is we who are determining the end of this world, and preparing the new world we desire.

St Ignatius, in one of the most powerful and central moments of the Spiritual Exercises, invites us to meditate on the “Two Standards.” It is a meditation of discernment to understand which “lord” we want to serve. Ignatius presents a symbolic scene: two “leaders” who gather their armies. Lucifer summons his followers on the great plain of Babylon. Christ, for his part, gathers his on the plain of Jerusalem. Their strategies are completely opposite.

Often, even without realising it, we follow one of these “lords”: either we belong to the team attempting to resume the construction of the tower of Babel, left unfinished (Gen 11), to reach “heaven”; or to the other team, striving to prepare the new Jerusalem. This work takes place here and now, in our great and small decisions, but continues into eternity.

The well-known Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain writes in The Things of Heaven that the damned are “active beings” who work all the time: “They will build cities in hell, towers, bridges; they will wage battles there. They will attempt to govern the abyss, to organise chaos.” But all of this is destined to collapse.

In heaven, on the other hand, work is directed towards preparing the heavenly Jerusalem, which John, the visionary of the world to come, beholds descending from above: “I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband” (Rev 21).

And so—which team do we support? Or rather, with which team do we play? Are we trying to rebuild the old world, despite all the failed attempts? Or do we want to make our life a brick in the city of the future?

The end of our life

For each of us, the world ends on the day of our death. It is the day of the great journey, if we may speak symbolically. Suddenly, we traverse billions of years and find ourselves in another dimension—the realm of the risen. There is no point trying to imagine it.

Wise is the person who gives meaning to life in view of this end.

One of the most beautiful and eloquent images used by Jesus to speak of the new world is the labour pains of childbirth: “When a woman is in labour, she is in pain because her hour has come; but when she has given birth to the child, she no longer remembers the suffering, because of the joy that a human being has been born into the world” (Jn 16:21). This labour is that of persecution, witness, and perseverance, says today’s Gospel.

But there is also a labour that does not give life: “As a pregnant woman about to give birth writhes and cries out in her pains, so were we before you, Lord. We conceived, we writhed in pain, as though to give birth; but we brought forth only wind. We have not brought salvation to the earth, and no people have been born” (Is 26:17–18).

Is our labour fruitful—bringing forth life—or is it sterile suffering, useless and wasted? Everything depends on what we nourish the womb of our heart with: the “word and wisdom” that Jesus promises to give us in today’s Gospel, or instead useless things, vainglory, vanity. As Qoheleth says: “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity!” (Eccles 1:2). So—are we pregnant with life or with vanity?

Fr Manuel João Pereira Correia, mccj

Courage, lift up your head!

Luke 21:5-19

Luke wrote his Gospel around the year 85 A.D. In the fifty years that passed since the death and resurrection of Jesus, tremendous events occurred. There were wars, political revolutions, catastrophes and the temple of Jerusalem was destroyed. Christians became victims of injustices and persecutions. How to explain these dramatic events?

Someone appeals to the words of the Master: “There will be great earthquakes, famines, and plagues; terrifying signs from heaven will be seen…they will lay their hands on you” (vv. 11-12). They begin to say: Here is the explanation—Jesus had foreseen everything. The misfortunes (especially the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem) are signs of the end of the world that is coming and that the Lord is returning on the clouds of heaven.

Today’s Gospel tries to answer these false expectations and corrects the wrong interpretation that some gave to the words of the Master. His apocalyptic language already lent itself to being misunderstood. Let’s look at the details of the passage.

Some people approach Jesus who is in the temple and invite him to admire its beauty: the huge white limestone rocks perfectly squared by the workers of Herod, the decorations, the votive offerings, the golden vines hanging from the walls of the vestibule and extending more and more through the branches offered by the faithful, the facade covered with gold plates with a thickness of a coin…. With reason, the rabbis maintain: “Who has not seen the temple of Jerusalem has not contemplated the most beautiful among the marvels of the world.”

The answer of Jesus is amazing: “There shall not be left one stone upon another of all that you now admire. Amazed, they ask him: When will this be and what will be the sign that this is about to take place?” (vv. 5-7).

Jesus cannot specify the date: He does not know it, as he does not know the day and hour of the world’s end (Mt 24:36). He is not a magician, a soothsayer, so he does not answer.

Why does Luke introduce this episode? He introduces it for a pastoral concern: he wants to warn his communities against those who confuse dreams with reality. Some exalted ones attributed to Jesus, predictions that were only results of extravagant speculations.

The evangelist invites the Christians to stop chasing fairy tales and to reflect on the one thing that should be of interest: what to do, specifically, to collaborate in the coming of the new world, the kingdom of God.

The “false prophets” have always represented a serious danger to the Christian communities. Luke records that Jesus is also bothered and warns his disciples against those who foretell that the end of the world is near. He strongly recommends: “Do not follow them” (v. 9). The end will not come soon; the gestation of the new world will be long and difficult.

What will happen in the time between the Lord’s coming and the end of the world? Jesus answers this question using the apocalyptic language. He talks about the uprisings of peoples against peoples, earthquakes, famines, and pestilences, terrifying events and great signs in heaven (vv. 10-11). These will be taken up and explained later: “Then there will be signs in the sun and moon and stars, and on the earth anguish of nations, perplexed by the roaring of the sea and its waves. People will faint with fear at the mere thought of what is to come upon the world, for the forces of the universe will be shaken” (Lk 21:25-26). What does he mean to say?

One of the recurring ideas in the time of Jesus was that the world had become too corrupt and that it would soon be replaced by a new reality made to sprout by God. It was said that people would be caught by great fear in the time of passage from the old to the new. The peoples and nations would be upset; there would be violence, diseases, misfortunes, and wars. The sun would appear during the night and the moon during the day; the trees would begin to shed blood and the stones to break into pieces and launch screams.

This language, these images were well known.

Jesus uses it to say to the disciples that the passage between two eras of history is imminent. His is a proclamation of joy and hope. Anyone in pain and waiting for the kingdom of God should know that the dawn of a new, wonderful day is about to appear. That is the reason that he urges the disciples not to be afraid: not to be frightened (v. 9) “When these things begin to happen, look up and lift up your heads because your redemption is near” (Lk 21:28).

After having invited them to consider the time of waiting for his return as a gestation that prepares for the delivery, Jesus pre-announces the difficulties that his disciples will have to confront (vv. 12-19).

What will be the sign that the kingdom of God is being born and established in the world? It’s not the triumphs, the applauses, the approval of people, but persecutions. Jesus foresees for his disciples: prison, slanders, betrayal by the family members and best friends. In these difficult situations, they may be tempted to become discouraged, to think to have made wrong choices in their lives.

Why endure so much suffering and make many sacrifices? It’s all to no avail: the wicked will always continue to prosper, to commit violence, to get the better of the righteous. Jesus says that this will not happen. God guides the events of people’s lives and directs the plans of the wicked to the good of his children and the establishment of the kingdom.

“Make up your minds not to prepare your defense yet”—he recommends. What does this mean? Will the disciples have to expect miraculous deliverances?

No. Jesus warns them of the danger of trusting in reasoning and calculations that people are wont to do.

If his disciples believe to be able to defend themselves using the logic of this world, instead of God’s, they will equate themselves with their opponents and will lose. They will have to happily accept the fact that they cannot resort to the methods of those who persecute them with slander, hypocrisy, corruption and violence. They must be convinced that their strength lies in what people consider as fragility and weakness. They are sheep among wolves; they cannot dress up as wolves. If they will really be consistent with the needs of their vocation Jesus, the Good Shepherd, will defend them. He will give them power no one can resist: the power of truth, love, and forgiveness.

Finally, Jesus draws an expression much used in his time: “Not a hair of your head will perish.” He does not promise to protect his disciples from any misfortune and danger. The persecuted Christians must not expect miraculous deliverances: they will lose their properties, work, reputation and perhaps even life because of the Gospel. However, despite contrary appearances, the kingdom of God will continue to advance.

Those who have sacrificed themselves for Christ, may not reap the fruits of the good they have sown, but must cultivate the joyful certainty that the fruits will be abundant. In this world, the value of their sacrifice will not be recognized. They will be forgotten, perhaps cursed, but God—and it is his judgment that matters—will give them the reward in the resurrection of the righteous.

Fernando Armellini

Italian missionary and biblical scholar