Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

Friday, November 28, 2025

On November 14th, 2025, Tangaza University had its second graduation ceremony following the acquisition of its Charter in May 2024. Included among the graduates was Bro. Christophe Blawo Yata, MCCJ, a formator at the Comboni Brothers Centre (CBC) in Nairobi. He obtained a PhD in Social Transformation, specializing in Governance. He got a distinction.

Walking with Community

A PhD Journey into Grassroots Agency and Urban Transformation

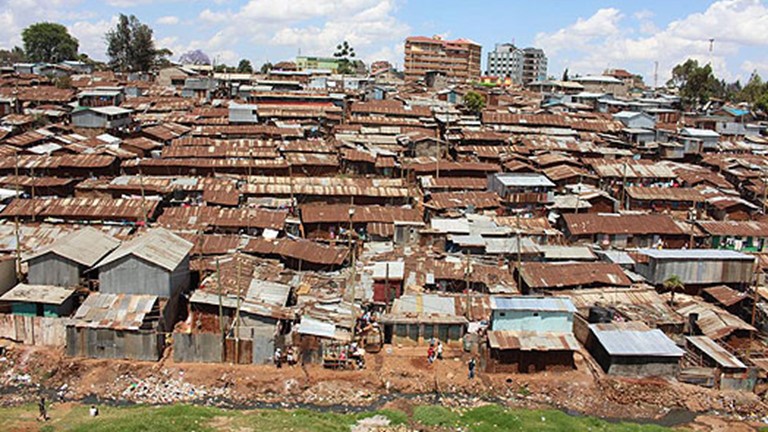

in Kibra Soweto-East (Nairobi Kenya)

A PhD journey is often described as a marathon of the mind, but for me, it became equally a journey of the heart and a journey of transformation. Over these years, my research “Grassroot Agency in Housing and Urban Transformation: A Phenomenological Inquiry into Government-Residents Dynamics in Kibra Soweto-East” took me far beyond theories, policies, and academic debates. It took me into the lived realities of a community whose resilience, creativity, and humanity reshaped my own understanding of social transformation.

My research transcended the boundaries of a conventional academic exercise, emerging at the intersection of an urban housing crisis and my engagement with the impacted communities. My positionality was inherently hybrid: as a Togolese Comboni Missionary (MCCJ) and scholar, I occupied both insider and outsider locations within Kibra. This liminal position not only facilitated access and trust but also shaped the framing of the study’s central questions.

My engagement with Nairobi’s informal settlement dates back to my pastoral work between 2011 and 2014, during which I collaborated with grassroots youth groups that had formed in the aftermath of the 2007-2008 post-election violence. Initially focused on peacebuilding, these movements gradually evolved into platforms for socio-economic empowerment and environmental justice. My subsequent mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (2014-2021) deepened my comparative understanding of urban informality, exposing similar struggles for dignity and belonging within Kinshasa’s peripheral settlements. In 2021, returning to Kenya felt less like relocation and more like resuming an unfinished conversation. Nairobi’s urban landscape had transformed through new infrastructure and redevelopment initiatives, yet persistent inequalities remained visible. My renewed involvement through the Kibra Social Justice Centre revealed a community both vibrant and contested, animated by tensions of exclusion and the energy of civic mobilization.

As a result of these encounters, the idea of a ‘house’ came out more significantly to represent dignity, identity, and self-determination rather than just being a physical building for residents of informal settlement. While government programs such as the Kenya Slum Upgrading Programme (KENSUP) and the Affordable Housing Initiative have attempted to address housing deficits, their implementation has often remained partial and exclusionary. These contradictions informed the study’s central inquiries: How do residents contribute to the making of the city? Who defines what constitutes a housing solution? Can mobilization from within informal settlements become a genuine force for urban transformation? I carried with me a burning curiosity: How do ordinary residents in informal settlements influence, negotiate, and reshape the processes that affect their homes and their lives?

From the outset, I knew that studying Kibra Soweto-East would demand more than academic rigor. I immersed myself in the vast body of literature on urban informality, housing policy, and participatory development. But behind every theory I read, I felt the presence of real people families, youth, community leaders whose voices were often missing in policy dialogues.

I was not just studying “urban transformation.” I was learning to listen using the pastoral cycle methodology. The data collection phase took me into the heart of Soweto-East. Through interviews, observations, and countless conversations, I met residents whose everyday acts of agency challenged conventional narratives about informal settlements. I witnessed mothers who organized community savings groups to strengthen their bargaining power. Youth who innovated small-scale livelihood projects. Local leaders who navigated complex government structures with courage. I encountered ordinary residents whose understanding of home stretched beyond walls and roofs into identity, dignity, and belonging. I interacted with a world called ‘slum’ by neoliberal perspectives yet is the expression of ‘citiness’ of the marginalized and excluded of the city. Collecting data meant more than filling notebooks and recording interviews. It meant being invited into lives, stories, fears, and hopes. And with each encounter, I realized that the community was not just my research site, it was my teacher, my inspiration.

As I analyzed the data, layers of meaning began to unfold. I saw patterns: the tensions between government-led upgrading and community-led initiatives, the informal power structures shaping negotiations, the subtle but powerful ways residents push back, adapt, or co-create transformation. But I also confronted the complexities of phenomenological research. How do you do justice to people’s lived experiences? How do you honor the authenticity of their voices in academic writing? How do you balance critical analysis with compassion? Yet, each insight reminded me why I began: to make visible the agency of people too often framed as passive recipients of policy.

Beyond theories of urbanization, my experience in Soweto-East taught me life lessons:

- Agency lives in ordinary people. Transformation does not only come from institutions, but from everyday acts of courage and collaboration.

- Communities understand their own needs best. Lasting development listens before it leads.

- Dignity is at the core of housing. A home is more than shelter it is security, identity, and aspiration.

- Research is a responsibility. To study people’s lives is to honor their truths with respect and integrity.

Reflecting on this journey, I see more than a completed dissertation. I see a journey that shaped me intellectually, emotionally, and ethically. As a Comboni Missionary, I understand the significance of St. Daniel Comboni's appeal for the marginalized and excluded to be agents of the change that impacts them.

My PhD was not just about understanding grassroots agency, it was about experiencing it. As I turn this chapter, I carry with me a deeper commitment to research that uplifts voices, informs policy, and inspires transformation. This journey may be complete, but the work of contributing to more inclusive, humane, and participatory urban futures continues. If this study has taught me anything, it is this: Real transformation begins when we truly listen to the people who live the realities we seek to improve. And for that insight, I will always be grateful.

Brother Christophe Blawo Yata, mccj