Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

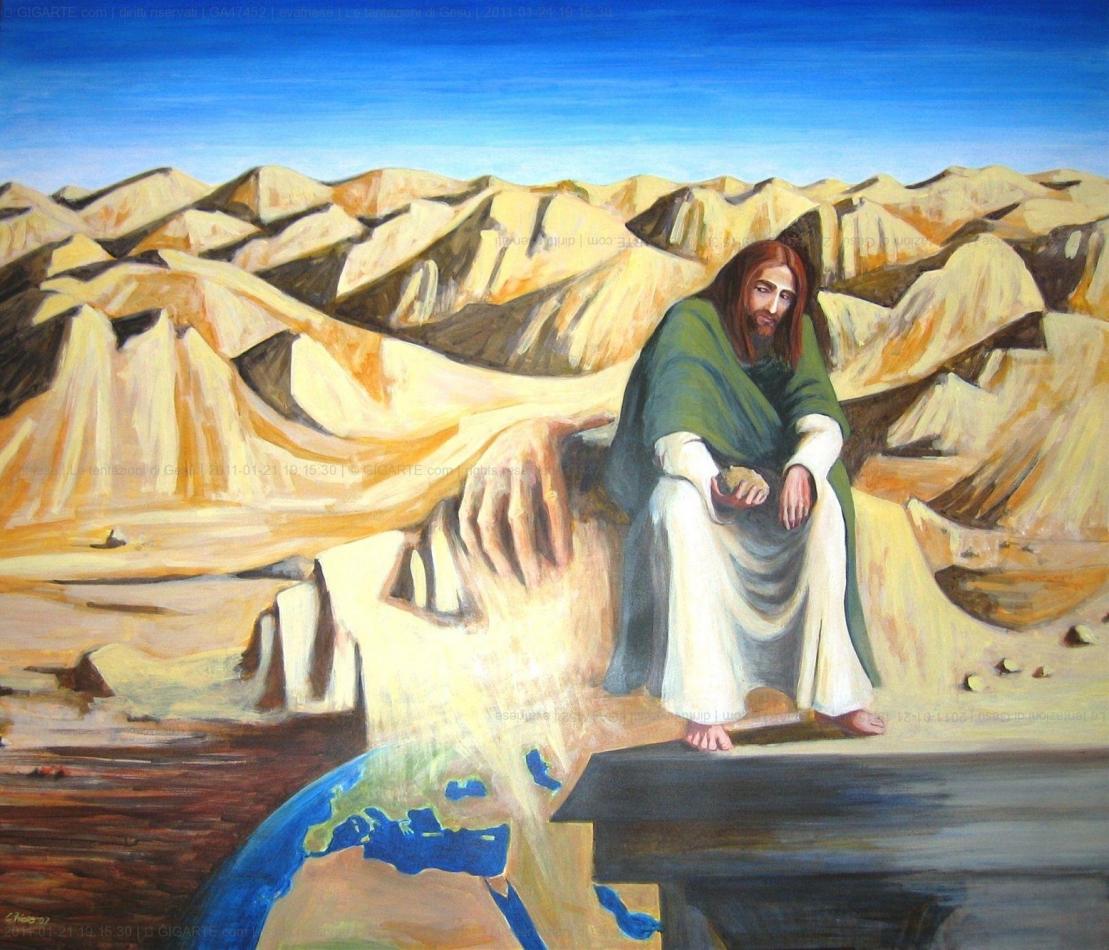

The Gospel of the second Sunday of Advent takes us into the desert to meet John the Baptist and to listen to the particular message he has to deliver on behalf of the God-who-comes. The desert is not a place that attracts us, unless we visit it as tourists, equipped with comfort and security. Moreover, the figure of John does not immediately appear appealing. (...)

“A voice crying in the wilderness: Prepare the way of the Lord!”

Matthew 3:1–12

The Gospel of the second Sunday of Advent takes us into the desert to meet John the Baptist and to listen to the particular message he has to deliver on behalf of the God-who-comes. The desert is not a place that attracts us, unless we visit it as tourists, equipped with comfort and security. Moreover, the figure of John does not immediately appear appealing. He is rough, not only in his manner of dress but especially in his words, which are almost aggressive. Yet we must meet him on our Advent journey. And after all, we must acknowledge that, although he is a rather unusual character, he is a special person — both for the kind of life he leads and for the freedom with which he speaks before political and religious authorities, which makes him a credible witness.

John, the son of a priest, had stripped himself of priestly garments and left the Temple to live in the desert, leading an austere life on the edge of survival. And “the word of God came to John, son of Zechariah, in the desert” (Lk 3:2). Then John began to preach: “Repent, for the Kingdom of God is close at hand!” These will later be the first words spoken by Jesus at the start of his ministry.

The prophets in Israel had been silent for a long time, and Israel hungered for the word of God. The rumour had spread that John was a prophet, and people flocked to him from everywhere. The simplicity and clarity of his message touched hearts and consciences, and all were baptised by him in the River Jordan, asking forgiveness for their sins.

People recognised in him the arrival of the Messenger foretold by Malachi, the last of the prophets: “See, I am sending my messenger to prepare the way before me” (3:1).

Thus was fulfilled the prophecy of Isaiah (40:3–5):

A voice cries out:

“In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord,

make straight in the desert a highway for our God.

Every valley shall be lifted up,

every mountain and hill be brought low;

the uneven ground shall become level,

and the rough places a plain.

Then the glory of the Lord shall be revealed,

and all flesh shall see it together,

for the mouth of the Lord has spoken.”

Two words stand at the centre of the prophecy: VOICE and WAY.

The Voice is that of John — strong and powerful like thunder, fiery like that of Elijah, sharp like a double-edged sword (Heb 4:12). It announces the voice of the Messiah who, as the first reading says (Is 11:1–10), “shall strike the ruthless with the rod of his mouth, with the breath of his lips he shall slay the wicked.” The appearance of this voice is already a gospel, a piece of good news. For all voices had been muffled, silenced, manipulated, bearers of falsehood. To hear that there is a new, free voice telling us the truth — even when it wounds us — is already a sign of hope.

“Prepare the way of the Lord!” The Lord’s way is the path that leads to Him, but above all the path that God travels to come to us. It is often a blocked road that must be cleared to make it passable.

The way is the image par excellence of the season of Advent. It is a symbol frequently found in the Bible. Let us remember that everything begins with Abraham’s journey, then that of the patriarchs, and of Moses who leads the people for forty years in the desert… Jesus himself, with his disciples, is always on the move, and the first Christians are called “the people of the Way”. Moreover, the way symbolises both the human condition — homo viator — and the believer, called to be part of a “Church that goes forth”, as Pope Francis liked to recall.

The prophet Isaiah (Deutero-Isaiah) was the architect, the road engineer, of the “way of the Lord”. John is the foreman. We must follow his instructions. Let us take up pickaxe, shovel, and spade. Yes, simple tools — for it is manual work, requiring time, perseverance, and patience. Following Isaiah’s plan, John gives us three main tasks:

“Every VALLEY shall be lifted up”: this is the first instruction. The evangelist Luke speaks of a ravine (3:5). It is the ravine of our DISCOURAGEMENT, into which we risk falling and becoming hopelessly trapped after so many attempts and failures. It is often a deadly danger, an abyss that buries all hope of human and spiritual progress. How can it be filled in? At times, it may seem almost impossible. What then? The only thing to do is to build a bridge — the bridge of hope in the “God of the impossible”. This is why Paul, in the second reading (Rom 15:4–9), invites us to “maintain HOPE alive”. Sometimes it means to “hope against all hope” (Rom 4:18), because “hope does not disappoint”… ever! (Rom 5:5).

“Every MOUNTAIN and hill shall be brought low”: this is the mountain of our PRIDE. Hill, mountain — sometimes even a massive peak difficult to climb. We get carried away with ourselves and imagine we are great. The “mountain” occupies the whole road, making it impassable. We must come down from our “heights” to make ourselves accessible — to God and to others. How many blows of the pickaxe are needed! How costly it is to become a flat valley where everyone may pass freely! Sometimes a bulldozer is needed to remove certain obstacles. It is the bulldozer of HUMILITY, sung by the Virgin Mary in her Magnificat. But let us not despise the small daily blows: a criticism accepted, an act of humble service, silence in the face of an unjust remark, a mistake that humiliates us… These will prepare us for the heavy bulldozer shovelfuls that life itself, sooner or later, will inflict upon us.

“The ROUGH GROUND shall become level and the rugged places a valley”: there are too many stones and brambles on the path, making travellers stumble and scratch themselves at every step. These are our DEFECTS and SINS, which often scandalise or wound others. Even here, unceasing work is needed, knowing full well that we will never completely succeed. Some sharp edges will stubbornly remain. Some brambles, cut back a hundred times, will spring up again each time, almost mocking our persistence. They are there to remind us that we cannot do without the MERCY of the Lord and of our brothers and sisters — and to remind us that we too must be merciful towards others. Paul reminds us again in the second reading: “Welcome one another, therefore, as Christ has welcomed you.”

These are the instructions of the foreman. A demanding task lies ahead. It is not a matter of doing a few small devotions, thinking ourselves good Christians in the style of the Pharisees and Sadducees who felt safe simply because they were children of Abraham. They too received baptism, but for many it was a mere formality, a superficial act. John, however, was not at all indulgent with them. He called them a “brood of vipers”. Let us beware lest he end up saying the same of us. And he adds: “Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire.” This is serious: let us not take lightly this grace of Advent.

Fr Manuel João Pereira Correia, mccj

Gospel Reflection

Matthew 3:1-12

She will flourish like the palm tree and will grow like a Lebanon cedar

Introduction

Israel was a tree that the Lord had germinated and then cultivated. Later the enemy came, armed with the lumberjack’s ax. They had smashed with merciless blows and reduced it to a bare and desolate trunk (Ps 74:5-6). It is our history. We are at the mercy of the forces of evil that enslave us. They take away the light and breath from us. We become dried branches, unable to bear fruit. But woe if we lose hope.

In the future days – the prophets assured – Israel will take root, blossom, and sprout and fill the world with fruit (Is 27:6). I shall be like the dew to Israel – the Lord says – like the lily will he blossom. Like a cedar he will send down his roots; his young shoots will grow and spread. His splendor will be like an olive tree, his fragrance, like a Lebanon cedar.

Nothing is impossible to him that has made even the dry stick of Aaron to flourish (Ex 17:3). According to the promises of the Lord, from the root of Jesse, a vigorous tree has sprouted – Christ – in which all are grafted. From him, the sap will come to maintain its lushness and will make every tree planted in the garden by God produce abundant fruit. There are no desperate situations for those who believe in the Lord.

Gospel: Matthew 3:1-12

At the time of Jesus, it was believed that Elijah did not die, but was taken to heaven to reappear one day. In fact, prophet Malachi foretold, “Behold, I am sending my messenger ahead of me to clear the way… I am going to send you the prophet Elijah before the day of Yahweh comes, for it will be a great and terrible day” (Mal 3:1,23).

After Easter, the early Christians realized that “the day of the Lord” was the one in which Jesus brought salvation. It even included who Elijah was, as spoken by the prophet. It was John the Baptist, instructed by God to prepare the people for the coming of the Messiah. “What was there to see? A man dressed in fine clothes? But people who wear fine clothes are found in palaces. What did you go out to see? A prophet? Yes, I tell you, and more than a prophet. For John is the one foretold in Scripture in these words: I am sending my messenger ahead of you to prepare your way” (Lk 7:25-27). “All the prophets and the Law prophesied until John. And if you believe me, he is that Elijah whose coming was predicted” (Mt 11:13-14).

Who was John? An enigmatic person! Josephus Flavius – the famous historian of the time – presented him thus: “He was a good man who urged the Jews to live a righteous life, treating each other with reciprocal justice and subordinating themselves with devotion to God and having themselves baptized. In truth, John was of the idea that not even this bath was acceptable as forgiveness for sins. He was convinced that it would be only a purification of the body if the soul had not been previously purified through right conduct” (1 Antiquities of the Jews, 8.5.2 & 116-119).

In today’s Gospel Matthew describes him as an austere man (v. 4). His food was simple like that of the inhabitants of the desert. His dress was rough, a leather belt around his waist that distinguished Elijah (2 Kg 1:8), and a fur cloak – a uniform of the prophets (Zec 13:4).

The whole person of John the Baptist was a condemnation and denunciation of the opulent society – then as now. It was aimed at the ephemeral, the frivolous, the false values of luxury and ostentation.

His message is summarized by the evangelist in a simple phrase, “Repent, because the kingdom of heaven is near” (v. 2).

The hope in a better future was one of the central themes of the message of the prophets. Unlike the other people who put their golden age in the past, Israel placed the reign of David in the future. It was waiting for a world where the Lord would have exalted harmony and made peace abound; a world where interpersonal relationships would be marked by love, reconciliation with nature, with people, with God.

The apocalyptic preachers had described the history of humankind as a succession of kingdoms of beasts. “Beasts emerged from the sea; they were the great empires of Babylon, Media, Persia and Greece” (Dn 7). Those were difficult times, but there was no need to lose heart: the ancient world had come to an end and the new world was about to burst.

The present pains should not be interpreted as signs of death, but as the suffering of a difficult childbirth: a prelude to the birth of the new era.

Since these are the expectations of the people, it is easy to see how the preaching of John would arouse great enthusiasm. Everyone was running to be baptized, to be introduced first into the kingdom of God.

Baptism by water was not enough. Jordan was not a pool from which one miraculously came out cleansed of sin. To be willing to enter into the kingdom, it was necessary to convert oneself, that is, to reverse the path, change course, to completely modify the way of thinking and acting. It was not enough to correct some moral behavior. It was necessary to put into action a new exodus.

They came to him from Jerusalem … Here are the people of Israel, established in the promised land, now abandoning their own condition of presumed freedom and returning to Jordan. They considered themselves free, but in reality, they continued to be slaves: of their own religious convictions, their obstinacy, the false image of God that they made.

They confessed their sins … They became aware of being still in exile, of being deprived of freedom.

Every year on the second Sunday of Advent, the liturgy offers Christians the preaching of John the Baptist. He prepared the people of Israel for the coming of the Messiah. So, also today, he is able to teach us to welcome the Lord who is coming.

Today, as then, the most difficult step to accomplish is to understand that it is a must to get out of the land where we are settled, leave the false religious and theological security that we constructed and welcome the newness of God’s word.

Not everyone has responded with solicitude to the invitation of the Baptist. Not all were willing to work a radical change of heart. The Pharisees and Sadducees … while intrigued by the preaching of John, found it hard to get involved. They did not trust him but preferred to keep their certainties (vv. 7-10). They thought they were already right with God for the fact of being children of Abraham. This false security will be reported later by a famous rabbinic saying: “As the screw rests on a dry wood, even so, do the Israelites rely on the merits of their fathers.”

The reproach with which the Baptist welcomes Pharisees and Sadducees is severe: “Brood of vipers!” He compares them to snakes that inject their poison of death in those who inadvertently come close to them. Then he moves on to the invective, the announcement of disasters that are about to hit them. They run the risk of being cut off like a tree that does not bear fruit and of being burnt like chaff. God’s wrath is incumbent on them.

We are faced with dramatic images that seem to refute the dream of Isaiah in the first reading.

The tone is threatening, and it is not surprising on the lips of John the Baptist. The preachers of that time expressed themselves that way. This is the language that often appears in the Bible. The precursor uses it to warn those who refuse the invitation to conversion; one is deprived of a loving encounter with Christ who comes to introduce him to his joy and his peace.

In the context of the whole gospel, the words of the precursor take on a meaning that goes beyond the immediate. It happened also for Caiaphas to say, without realizing it, a prophecy (Jn 11:49-51).

When he spoke of God’s wrath, John had no clear idea of how it would manifest.

The wrath of God is an image that recurs often in the Old Testament. It is not intended as an explosion of hatred on the victim. It is an expression of God’s love: he rails against evil, not against the person who does it. He does not want to hit the person, but to free each one from sin.

The ax, which cuts the trees at the root, has the same function given by Jesus to the scissors pruning the vine and freeing it from useless branches that deprive it of precious sap and suffocate it (Jn 15:2). The trees uprooted and thrown into the fire are not the people that God always loves as children, but the roots of evil that are present in every person and in every structure and need to be cut to pieces so that the healthy ones can sprout more buds (Mt 3:10).

The cuts are always painful, but those done by God are providential. They create the conditions for new branches to sprout and produce fruits.

The fan, finally, with which the Lord realizes his judgment, is a living image. It describes the way in which the work of every person is screened by God.

In human courts, judges take into account only the errors and pronounce judgment on the basis of the harm done. They take little account of good works. In the judgment of God, the exact opposite happens: He, with the winnowing fan of his word, puts every person under the discerning breath of his Spirit that blows away the chaff and leaves on the threshing floor only the precious grains: the works of love, few or many, that each one had performed.

by Fr. Fernando Armellini

Fernando Armellini is an Italian missionary and biblical scholar. With his permission we have begun translating his Sunday reflections on the three readings from the original Italian into English.

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com