Daniele Comboni

Missionari Comboniani

Area istituzionale

Altri link

Newsletter

In Pace Christi

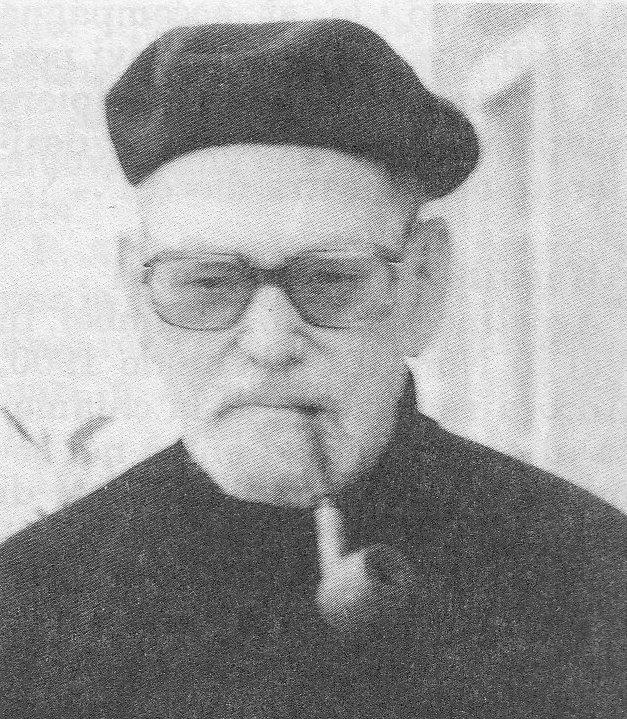

Pellegrini Agostino

Terminata la terza teologia nel seminario di Trento, il chierico Agostino Pellegrini decise di fare il passo che lo avrebbe portato tra i missionari comboniani.

Scrisse il rettore del seminario in data 15 aprile 1923:

"Licenziando il chierico Pellegrini Agostino che col permesso del Vescovo diocesano aspira alle sante missioni, posso certificare con piacere che questo aspirante merita ogni migliore raccomandazione per le sue qualità intellettuali e morali.

Fornito di buona intelligenza egli mostrò in questo seminario sempre assidua diligenza nello studio, come appare anche dai suoi attestati annuali, e non minore fu la sua premura nel formarsi spiritualmente. Mentre si licenzia da questo seminario per darsi al nobilissimo ufficio di missionario, lo si accompagna coi più vivi desideri che ivi possa, con la grazia di Dio, compiere quell'opera che si avrebbe desiderato nella nostra diocesi".

Affascinato da Comboni

Agostino era nato a Dambel, in Val di Non, il 21 gennaio 1900. Ancora ragazzo sentì la chiamata al sacerdozio ed entrò nel seminario minore della diocesi di Trento.

Studente di liceo, nel pieno della prima guerra mondiale (1917), fu arruolato nell'esercito austroungarico. Fu soldato per pochi mesi, ma furono sufficienti perché il giovane seminarista potesse seminare il buon esempio tra i commilitoni. Finita la guerra, tornò in seminario a continuare gli studi.

Negli anni Venti, il nostro giovane conobbe i missionari comboniani che, a quel tempo, tenevano aperta una scuola apostolica a Trento. L'eroica vita missionaria del loro fondatore, mons. Daniele Comboni, lo affascinò a tal punto da decidersi a consacrare la propria vita alle missioni dell'Africa.

Entrò in noviziato, a Venegono Superiore, il 17 giugno 1923, a 23 anni, dopo aver frequentato il terzo anno di teologia nel seminario di Trento.

Era maestro dei novizi p. Bertenghi, un uomo in cui la santità e la capacità di formare i futuri missionari andavano di pari passo. Si prese una cura tutta particolare del nuovo arrivato anche perché ormai era prossimo all'ordinazione sacerdotale. Scrisse di lui:

"Ha molta buona volontà ed è molto pio, umile e osservante. In seminario aveva terminato gli studi di dogmatica; gli restava qualche parte di morale e di diritto canonico. In noviziato sta studiando questi trattati. Come intelligenza non mi pare una cima, anche se sa cavarsela discretamente. Probabilmente si tratta di una forma di esaurimento che lo perseguita perché le note arrivate dal suo seminario sono ottime sotto tutti gli aspetti.

Come carattere è piuttosto timido e impacciato, ma è schietto e docile. la sua salute è piuttosto fragile. Certamente ha risentito delle restrizioni e della fame imposte dalla guerra. In vista di questo gli ho concesso un orario più largo rispetto agli altri novizi.

Spera di essere ordinato sacerdote dopo il primo anno di noviziato. Io gli suggerirei un buon soggiorno nelle sue arie del trentino in modo da riprendere vigore. 10 maggio 1924".

Non sappiamo se andò al paese a rimettersi in salute. Sappiamo che il 16 luglio di quel 1924 emise la prima professione, quindi dopo un solo anno di noviziato, e venne ordinato sacerdote a Milano dal card. Eugenio Tosi il 2 novembre 1924. Era il giorno dei morti: le anime del purgatorio gli portarono bene.

Sulle orme del Fondatore

Dopo qualche mese, s'imbarcò a Napoli per l'Africa insieme al novello vicario apostolico, mons. Tranquillo Silvestri. Battendo le piste del Fondatore, attraversò il deserto e giunse a Khartum. Dopo Khartum, ancora due settimane di battello per approdare a Juba (Bahr el Jebel), capolinea del Sudan allora angloegiziano. Era il primo luglio 1925.

In quel tempo gli inglesi erano ancora occupati a sottomettere le tribù del sud e per questo aprivano grandi strade e costringevano la gente a sistemarsi in prossimità di esse.

Un certo capitano inglese di nome Driberg, prima conquistatore e poi amministratore di quelle zone (si trattava del distretto orientale verso l'Etiopia, che comprendeva le tribù dei topossa, dei didinga e dei longarin detti anche boya), chiese la presenza di una missione cattolica perché lo aiutasse ad avere un contatto di vera amicizia con le popolazioni ancora molto diffidenti verso i nuovi venuti. I

Il capitano era convinto che l'insegnamento della religione cristiana e l'educazione scolastica fossero basilari per una vera civilizzazione.

La posizione scelta dal capitano Driberg per la missione non era nella pianura di Kapoeta fra gli assai più numerosi topossa, ma accanto alla sua residenza sull'altopiano di Naghichot nel territorio didinga, a duemila metri sul livello del mare. Quest'uomo era una specie di "re sagrestano" che strumentalizzava i missionari e la religione per i suoi interessi. Anche quanto a evangelizzazione, visite ai villaggi, lavoro catechistico... "non si muove foglia che Driberg non voglia".

P. Agostino Pellegrini fu scelto per la nuova fondazione. Con lui andarono anche altri due missionari, p. Molinaro e fr. Bertagnoli.

La spedizione partì da Juba, a piedi, con una dozzina di portatori e così, uno dopo l'altro, coprì i 300 chilometri che separano Juba da Naghichot, seguendo sentieri tortuosi per evitare foreste e paludi.

Dopo una settimana erano a Torit, centro principale della tribù lotuko e sede di una iniziale missione cattolica. Poi avanti per un'altra settimana attraversando un'immensa savana disabitata e paradiso di tutti gli animali selvatici: antilopi, zebre, giraffe, leoni, leopardi, cinghiali... Mancava la strada e spesso anche ogni traccia di sentiero.

Speranze e delusioni

Stremata di forze, la comitiva arrivò a Naghichot. Il capitano aveva preparato per i missionari una casetta fatta di tronchi d'albero. A quell'altitudine faceva freddo. "Cercammo del muschio per chiudere le fessure fra tronco e tronco" raccontò p. Pellegrini. La povertà era estrema.

Naghichot poteva essere un centro turistico per europei ben equipaggiati, ma non per gli africani sprovvisti di tutto. Di fatto i villaggi degli indigeni erano molto più in basso ove il clima era più mite. Il capitano obbligò i capi locali a mandare dei ragazzetti per iniziare una scuola, anzi, alcuni ne reclutò a più riprese con la forza dei soldati.

"Quei ragazzetti tutti nudi passavano il tempo attorno al fuoco per scaldarsi e qualcuno, quando poteva, se la dava a gambe e tornava al suo villaggio", ricordò p. Pellegrini.

Dopo Natale del 1925 p. Vignato fece una visita ai confratelli di Naghichot. Scrisse in data 15 gennaio 1926 a p. Meroni, sup. generale: "Vi trovai p. Pellegrini vegeto e fresco come era in Italia, beato nella sua solitudine. La stazione è su una magnifica collina dell'altipiano. Vi hanno tutta l'ortaglia che si può avere in Europa nei paesi freddi. Riuscì la coltivazione delle patate. Ma la missione è una vera solitudine: 17 ragazzi didinga sempre ripiegati su se stessi per il freddo, alcuni catechisti dongotono, due servetti e niente altro".

Le poche provviste si esaurirono presto e con Juba non c'era comunicazione. Così non si poteva andare avanti. Di conseguenza dopo un anno la missione fu abbandonata e il Padre andò a Torit, rimandando a tempi migliori la fondazione della missione tra i didinga.

11 anni a Torit

Dal 1926 al 1935 p. Pellegrini rimase a Torit come addetto al ministero e poi superiore. Imparò la lingua dei lotuko alla perfezione. La popolazione rispondeva bene e i missionari spendevano le loro giornate a visitare i villaggi e a stare a lungo con la gente. Sorsero catecumenati, scuole elementari, una scuola tecnica con officina meccanica, falegnameria e calzoleria.

Vacanze e prigione

Nel 1935 p. Pellegrini ebbe le sue prime vacanze in Italia durante le quali andò per cinque mesi in Inghilterra a imparare l'inglese.

Nel 1936 era a Isoke, fra i dongotono nel distretto di Torit. Vi rimase un anno per tornare nuovamente a Torit (1937-1940) come superiore e parroco.

Poi ci fu la stasi della seconda guerra mondiale che tante privazioni (di personale e di mezzi) impose alle missioni. I missionari, inoltre, furono messi in campo di concentramento a Okaru, e tenuti sotto vigile sorveglianza da parte degli inglesi. L'Italia, infatti, era in guerra con l'Inghilterra. Solo quando il conflitto ebbe termine, i missionari tornarono alle loro opere.

Dal 1942 al 1943 p. Pellegrini fu a Kapoeta, tra i topossa, ma la missione toccava anche i didinga e i boya. Fondatore di Kapoeta fu p. Sisto Mazzoldi. Era accompagnato da p. Lino Spagnolo e fr. Giuseppe Galli.

P. Sisto Mazzoldi si spinse fino a Cukudum, a 90 chilometri da Kapoeta ai piedi dei monti di Naghichot. E nel 1946 sorse la nuova missione.

Ritorno al primo amore

Per la fondazione di Cukudum fu scelto p. Pellegrini.

Fu un giorno bello per il Padre tornare tra i didinga lasciati 20 anni prima e mai dimenticati. A Cukudum, proprio ai piedi delle montagne, il clima era buono, c'era acqua in abbondanza, i villaggi degli indigeni erano vicini, il terreno appariva fertile e, tutto intorno, si stendeva una foresta di bambù che assicurava legna per le future fornaci di mattoni e tegole.

Compagno di missione fu p. Michele Rosato, appena arrivato dall'Italia. I due lavorarono assiduamente insieme per quattro anni ottenendo ottimi frutti di apostolato. Ma la vita era dura. L'unico mezzo di trasporto disponibile in missione era un carretto trainato dagli asini. I missionari vissero in capanne povere, infestate da pulci penetranti. Per la vita dei missionari a Cukudum si può vedere il libro di p. Rosato "50 anni d'Africa" e c'è da rabbrividire.

Dopo sei mesi dal loro arrivo, giunse fr. Lazzari, mandato da Juba per vedere come i due se la passavano. Scrisse: "Mi sembrò di incontrare Robinson Crosoè e suo figlio. Capelli lunghi (mai tagliati) barba selvaggia, mani incallite, vestiti a brandelli, zoppicanti da ambo le gambe per le tante pulci che avevano fatto i loro nidi sotto le unghie dei piedi".

Gli asini non sono stupidi

Siccome metà del territorio poteva essere visitato solo col cavallo di san Francesco attraversando le montagne, p. Pellegrini cercò di organizzarsi con l'aiuto di tre asini, ma purtroppo l'impresa non riuscì. Nel viaggio inaugurale gli asini partirono spediti, ma quando cominciò la salita del monte, non ci fu verso di farli proseguire. Finché ad un certo punto fecero dietrofront e ritornarono alla missione trotterellando e ragliando di gioia, piantando a mezzo monte il povero condottiero. E poi dicono che gli asini sono stupidi!

Solo nel 1950 i tre di Cukudum poterono entrare nella nuova casa. Poi arrivarono anche le suore e la vita cambiò.

Cukudum intanto divenne il centro dei didinga con dispensario, scuola elementare, catecumenato, agricoltura d'avanguardia con l'introduzione di nuove sementi e un aratro trainato dagli asini. I missionari si erano dotati di bicicletta.

A Cukudum furono portate e piantate in gran quantità banane, papaie, manghi, mandarini, aranci, gawafe, limoni, ecc. Tutte piante prima sconosciute ai didinga che coltivavano solo sorgo, granoturco e sesamo.

Pipa e rosario

Per l'Anno Santo del 1950, p. Agostino venne in Italia per un meritato riposo. Ma la vacanza durò poco. La sua passione era l'Africa. Vi tornò e fu destinato ad Isoke dove rimase due anni. Nel 1953 era di nuovo a Torit. I viaggi apostolici a Torit, tra i lotuko erano meno faticosi che tra i didinga dove ci si poteva muovere solo a piedi, tra i sentieri delle montagne.

Dopo altri tre anni ad Isoke (1956-1959) chiese di essere inviato tra i didinga. E nel 1960 lo troviamo nuovamente a Cukudum. Pensava di restarci per sempre. Il Padre ormai si era fatto pesante e faticava a camminare, allora dedicava il suo tempo ai catecumeni, alla cura dell'orto e del frutteto e alla preghiera. Due cose portava sempre con sé: il rosario e la pipa.

Persecuzione

Ma ormai la pressione musulmana si faceva sentire. Il governo di Khartum vedeva nella presenza dei missionari cristiani un ostacolo all'espansione della religione islamica nel Sudan.

Già nel 1957 (una anno dopo l'indipendenza) alle chiese cristiane erano state tolte le scuole e i dispensari; erano stati negati i permessi di aprire altre missioni o iniziare nuove opere.

Nel 1962 venne emanato il "Missionary Act" che costituì un capestro per le missioni (quando papa Giovanni Paolo II andò in Sudan nel 1993, chiese espressamente al governo sudanese, come gesto di buona volontà, l'abrogazione di questa legge, ma fu inutile).

Praticamente i missionari erano ridotti a domicilio coatto e per muoversi occorreva un permesso scritto volta per volta.

Già nel 1962 cominciarono le prime espulsioni (come abbiamo visto con p. Negrini); nel 1963 altri subirono la stessa sorte. Tra questi anche p. Pellegrini. Lasciò Cukudum il 18 gennaio 1963.

Il Padre era profondamente commosso. Non riusciva a rendersi conto come fosse possibile l'espulsione da quella terra dove aveva prodigato le sue energie giovanili sottoponendosi a sacrifici di ogni genere per il bene della gente.

Prima di lasciare la missione invitò tutti i presenti a mettersi in ginocchio per ricevere la sua ultima benedizione. L'ufficiale arabo che era presente domandò a p. Petri: "Qund'è che il Padre è arrivato a Cukudum?". "Quando lei non era ancora nato", fu la risposta. Il soldato rimase a lungo in silenzio, estremamente impacciato di dover eseguire quell'ordine.

In Italia

Rientrato in Italia il 21 settembre 1963, p. Agostino venne assegnato come confessore nella scuola apostolica di Barolo.

Alla chiusura di questo seminario passò in Casa Madre come addetto al ministero. Dopo un periodo di cura nella stessa Casa Madre fu assegnato alla comunità di Arco. Qui passò gli ultimi anni della sua vita, finché fu portato nuovamente a Verona con gli anziani del Centro Assistenza.

P. Rosato ci dà un ritratto spirituale di questo nostro confratello: "P. Pellegrini era un uomo dal carattere calmo e un po' lento, ma costante. Aveva una gran dose di criterio e moltissimo zelo per la salute delle anime. Non esitava a sporcarsi le mani per la coltivazione dei campi di patate dolci per il mantenimento dei catecumeni in continuo aumento. Anche per la realizzazione dei fabbricati era instancabile. Si offriva nei momenti liberi dal ministero a impastare tegole e mattoni insieme ai ragazzi e ai giovani.

Amava intrattenersi in lunghi discorsi con la gente. Dagli anziani apprendeva gli usi e i costumi della tribù e ai ragazzi spiegava i racconti del vangelo e della sacra Scrittura. Siccome conosceva alla perfezione la lingua, questo compito gli riusciva facile.

Visitava i malati e aiutava chi era nel bisogno. Per questo fu subito stimato dalla gente che lo amava come uno di loro. Anche lui amava molto il suo popolo e certamente avrebbe voluto terminare i suoi giorni in Sudan. Conosceva molto bene il lotuko, il didinga, il bangala, l'inglese e il tedesco.

Con i confratelli era mite e disponibile. Ha coperto per molti anni il ruolo di superiore, ma il suo fu un vero servizio. In comunità era un elemento che favoriva la distensione e il buon umore con le sue battute intelligenti e argute. E' stato un autentico missionario di quelli della prima ora che, per il Regno di Dio, non ha badato a rinunce e sacrifici. Sono certo che il Signore gli ha dato una ricca corona di gloria".

Una lettera

Nell'aprile del 1995 p. Petri ricevette da Juba una lettera nella quale un gruppo di didinga faceva menzione delle feste celebrate per i 70 anni di vita cristiana della loro tribù. Il Padre fu incaricato di portare la notizia anche a p. Pellegrini che allora si trovava a Verona presso il Centro Ammalati. "Andai a trovare p. Agostino - scrive p. Petri - e gli dissi della lettera da Juba, dei saluti, del grazie dai suoi didinga. Il Padre si rianimò un momento, alzò la testa, mi guardò e disse: 'Abunnà gerret" che in lingua didinga vuol dire 'è molto bello'".

La morte lo colse per collasso cardiaco, ricco di giorni e di meriti. Aveva 95 anni. Dopo il funerale in Casa Madre è stato portato al Dambel dove è venerato come un padre della fede nel cuore dell'Africa e un protettore del paese.

(P. Lorenzo Gaiga)

Da Mccj Bulletin n. 190, gennaio 1996, pp. 73-79

*****

At the end of his third year of Theology in the seminary of Trento, the cleric Agostino Pellegrini decided on the step that would take him into the ranks of the Comboni Missionaries.

The Rector wrote, on 15th April 1923:

"In discharging the cleric Pellegrini Agostino, who with the Bishop's permission aspires to the holy Missions, I have the pleasure to certify that this aspirant merits the best of recommendations, for both his intellectual and his moral qualities.

"Well-gifted intellectually, he has always given careful attention to his studies in the seminary, as the annual reports demonstrate; and his attention to his spiritual formation has been equally rigorous. As he leaves this seminary to dedicate himself to the most noble missionary calling, he is accompanied by the liveliest hopes that he may, with God's grace, carry out the work that we would have expected from him in our Diocese."

Fascinated by Comboni

Agostino was born at Dambel, in Val di Non, on 21st January 1900. He felt called to be a priest while still very young, and entered the Junior Seminary of the diocese of Trento.

While still in liceo, with World War I still raging (1917), he was conscripted into the Austro-hungarian army. He was a soldier for just a few months, but they were enough for the young seminarian to leave a lot of good example behind among his fellow conscripts. Straight after the war he went back into the seminary to take up his studies again.

In the next few years he got to know the Comboni Missionaries, who had a junior seminary in Trento in those days. The heroic missionary life of their founder, Bishop Daniel Comboni, fascinated him; so much so that he decided to consecrate his own life to the African missions.

He entered the Novitiate at Venegono on 17th June 1923. He was 23 himself and, as we have seen, had just completed the third year of Theology.

The Novice Master was Fr. Bertenghi, a man in whom holiness and the ability to form future missionaries went hand in hand. He paid special attention to the new arrival, because he was not far off ordination. He wrote:

"He has plenty of good will, is pious, humble and keeps the rules. In the seminary he had completed the study of Dogma, and still had part of Moral Theology and Canon Law to study. He is studying these treatises during the Novitiate. As intelligence goes he is not brilliant, but manages quite well. Maybe he is rather run down, because the reports that came with him from the seminary are excellent under all aspects.

His character is a bit shy and awkward, but he is open and obedient. His health is not too strong; I think he must have suffered from the scarcities and from hunger during the war. In view of this I have given him an easier time-table than the rest of the novices.

He hopes to be ordained at the end of the first year of Novitiate. I would suggest he have a good rest in the Trentino air, to recoup his energies. 10th. May 1924."

It is not recorded whether he did have a long rest in the air of his native Trento. But on 16th July 1924 he made his first Vows - so after just one year of Novitiate - and was ordained priest in Milan by Cardinal Eugenio Tosi on 2nd. November 1924: the Souls in Purgatory brought him a blessing!

In the footsteps of the Founder

A few months later, he set sailed for Africa from Naples, with the new Vicar Apostolic, Bp. Tranquillo Silvestri. Following the route of the Founder, he crossed the desert to reach Khartoum. After that, another two weeks on the river-boat to land at Juba (Bahr el Jebel), the terminus in the then Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. It was 1st July 1925.

In those days the British were still busy bringing the southern tribes under control; to do this they drove roads through the area, and forced the people to live along them.

A certain Captain Driberg, conqueror and then administrator of part of the area (the Eastern District, towards Ethiopia, including the Toposa, Didinga, Longarin - or Boya - tribes), had asked for a Catholic mission to be based there, to help him to build up friendly relations with the people, who were still very suspicious of the new arrivals. The Captain was convinced that religious instruction and schools were the very basis of civilisation.

But the position chosen for the Mission by Captain Driberg was not down on the plain of Kapoeta among the more numerous Toposa, but next to his residence on the plateau of Naghichot, in Didinga territory, and over 6,500 feet above sea level. The man was a kind of Emperor Franz Josef, (who used to be called "King Sacristan") because he used the missionaries and religion for his own purposes. He even controlled all the movements and activities of the missionaries for evangelisation, pastoral visiting and catechesis: nothing was done without Driberg's say-so.

Fr. Agostino was sent to the new foundation, together with Fr. Molinaro and Bro. Bertagnoli.

The expedition left Juba on foot, with a dozen porters, and covered, one at a time, the 180 miles to Naghichot, making several detours around forests and swamps.

It took them a week to reach Torit, the main centre among the Lotuko tribe, and site of one the early Catholic missions. From there they travelled for another week, crossing a vast and virtually trackless savannah, a paradise of wild animals: antelopes, zebra, giraffes lions, leopards, wild boars...

Hopes and disappointments

The little group arrived at Naghichot exhausted. The Captain had built them a log cabin. At that height, it was cold!

"We looked for moss to plug the gaps between the logs," Fr. Pellegrini reported. Their poverty was extreme.

Naghichot would have made a fine spot for well-equipped tourists or campers. But not for people with little or nothing. The local people lived much further down, where it was milder. But the Captain ordered the local chiefs to send up the children to school, and periodically send soldiers down to round them up.

"Those little children, with no clothes, used to huddle round the fire to try to keep warm; and when any of them got the chance, off they would go!" Fr. Agostino recalled.

Following Christmas 1925 Fr. Vignato arrived to visit his confreres, and reported to Fr Meroni, the Superior General, on 15th January 1926: "I found Fr. Pellegrini all fresh and lively, perfectly happy in his solitude. The mission is on a magnificent rise on the plateau. They can grow all the vegetables one finds in Europe; even potatoes have given a good crop. But the mission is really desolate: 17 Didinga children, constantly huddled against the cold, a few Dongotono catechists, a couple of houseboys, and nothing else."

The few essentials brought with them ran out, and Juba was too far away for any realistic contact. Things could not go on like that, and after a year the Fathers, abandoned the mission and withdrew to Torit, leaving a mission among the Didinga to wait for better times.

Nine years at Torit

Fr Pellegrini worked at Torit from 1926 to 1935, first as assistant priest, then as superior. He learned Lotuko perfectly, and the people responded well to the missionaries' efforts. They would spend days visiting the villages, spending hours among the people. Catechumenates sprang up, and primary schools appeared, along with a technical school, and workshops for mechanics, carpentry and shoe-making.

Holidays and... prison

In 1935 Fr. Pellegrini returned to Italy for his first leave, five months of which were spent in England to learn the language. In 1936 he was posted to Isoke, among the Dongotono of Torit District. He stayed there a year, then returned to Torit as superior and parish priest (1937-1940).

Then came the hiatus of World War II, which caused personnel and supplies for the missions to dwindle to nothing. The missionaries themselves were interned at Okaru, under the watchful eye of British troops. The missionaries were able to get back fully to their work only at the end of hostilities.

Fr. Pellegrini spent 1942-3 at Kapoeta, which was among the Toposa, but included some Didinga and Boya. He had Fr. Lino Spagnolo and Bro Giuseppe Galli with him. Kapoeta had been founded by Fr. Sisto Mazzoldi, who pushed on to Chukudum, about 60 miles from Kapoeta, at the foot of the Naghichot hills. There, in 1946, the new mission was built.

Return to his first love

Fr. Pellegrini was chosen for the parish when Chukudum was started. It was a great joy to return among the Didinga he had left 20 years previously, but had never forgotten. And at Chukudum the climate was very good, there was plenty of water, there were villages dotted all round, the land seemed fertile, and a bamboo forest promised good supplies for future brick and tile kilns.

Fr Michele Rosato, who had just arrived from Italy, was sent as assistant. The two worked hard together for four years, and obtained very encouraging results. Life was not without its hardships, though. Their only transport was a cart, drawn by asses. The missionaries lived in huts infested by jiggers. Their life is described by Fr. Rosato in his book: "50 Years in Africa", and at times sends shudders down your spine!

After the first six months Bro. Lazzari arrived, sent from Juba to see how the two were managing. He wrote: "I felt I was meeting Robinson Crusoe & Son! Long hair (never a haircut), wild beards, calloused hands, clothes in rags, limping on both legs because of the jiggers under their toe-nails..."

Donkeys are not stupid

Since half the territory could only be visited by hiking among the mountains, Fr. Pellegrini tried to organise things by using three donkeys as pack animals - but without success. On the first trip they trotted off quickly enough, but as the slopes became steeper they became more and more difficult to drive. In the end they all turned round and went trotting off back home, braying with relief, and leaving their poor master alone, and "neither up nor down"! And people will say that donkeys are stupid!

The three fathers at Chukudum were able to move into a new house only in 1950. And then the Sisters arrived, and things began to improve.

In the meantime, Chukudum had become a centre for the Didinga, with a dispensary, a primary school, the catechumenate, advanced agricultural methods with the introduction of new seeds and a plough pulled by... donkeys. The missionaries had got bicycles. Various kinds of fruit-trees had been planted: paw-paws, oranges, lemons, tangerines, guavas, mangoes, as well as bananas. Nearly all plants unknown to the Didinga, who cultivated only sorghum, maize and finger-millet.

Pipe and Rosary

In Holy Year (1950) Fr Pellegrini returned to Italy for a well-earned rest. But the holiday did not last long. His passion was for Africa. He went back as soon as he could, and was appointed to Isoke, where he stayed two years; then in 1953 returned to Torit. The missionary safaris among the Lotuko were less wearing than among the Didinga, with all the up-and-down mountain paths.

But after spending three more years at Isoke (1956-1959) he asked to be sent back among the Didinga; and in 1960 we find him at Chukudum once again. He looked forward to ending his days there. He had put on weight, and found it harder to get around on foot, so he concentrated on the catechumens, on overseeing the cultivation and the fruit trees, and on prayer. He never went anywhere without two objects: his rosary and his pipe.

Persecution

But Moslem pressure was growing in the South. The Khartoum government saw the missionaries as an obstacle to the spread of Islam in Southern Sudan. In 1957, only a year after Independence, the schools and dispensaries had been taken from the Christian churches; permission to open new missions or begin new projects was denied.

In 1962 the "Missionary Societies Act" was passed, designed to hobble all missionary activity (when Pope John Paul II went to Khartoum in 1993, he expressly asked the government to abrogate the Act as a sign of goodwill - without success). The missionaries found themselves practically under house arrest, since they needed written permission each time they wanted to move.

The expulsions began in 1962 (as we saw, Fr Negrini was one of the first victims). In 1963 others followed, one of them being Fr Pellegrini; he left Chukudum on 18th January 1963. He was anguished and bewildered; he could not take in the fact that he was being thrown out of the land where he had exhausted all his youthful energies, putting up with hardships of all kinds, for the love of the people.

Before leaving the mission, he asked everyone to kneel for his blessing. The Arab official overseeing his departure asked: "When did the father come to Chukudum?" "Before you were born!" they answered. The soldier fell silent, acutely embarrassed by the duty he had to perform.

In Italy

On his return to Italy on 21st September 1962, Fr Agostino was sent to the junior seminary at Barolo, as confessor. Then, when that seminary closed, he moved to the Mother House for ministry. After some medical attention there, he went on to the community at Arco, where he spent his remaining years, before having finally to return to the Centre for Sick Confreres in Verona.

Fr. Rosato provides this picture of him: "Fr. Pellegrini was calm, rather deliberate, but very steady. He had a lot of common sense and a great zeal for the salvation of souls. He did not hesitate to dirty his hands cultivating fields of sweet potatoes for the ever-increasing numbers of catechumens. And he was tireless in building work, too. At times when he was free from ministry he would tread mud for bricks or tiles, along with the young men and boys.

He loved spending time talking to people. He learned the traditions and customs from the elders, and told stories from the Bible to the children; and because he had learned the language perfectly, this was a pleasant task for him. He would visit the sick, and help those in need. All this made him much loved by the people, who counted him as one of themselves. He too loved the people very much, and would certainly have preferred to end his days in Sudan. He had a good command of Lotuko, Didinga, Bangala, English and German.

He was mild and friendly towards confreres. He held the office of superior for a number of years, and for him it was always a service. In community he fostered distension and good humour with his intelligence and wit. He was one of the great pioneer missionaries who, for the sake of the Kingdom of God, took privations and hardships in their stride. I am sure that the Lord has given him a rich crown of glory."

A Letter

In April 1995 Fr. Petri received a letter from the Didinga group in Juba, describing their celebrations for the 70 years since Christianity had been brought to their tribe. Father was asked to take the news to Fr. Pellegrini, who was then in the CAA in Verona. "I went to see Fr. Agostino," writes Fr. Petri, "and told him about the letter from Juba, the greetings and the thanks from his Didinga. He livened up for a moment, raised his head, looked at me and said Abunnà gerret!, which in Didinga means `That is very good'."

He died of heart failure, rich in days and merits. He was 95 years old. After the Requiem in the Mother House he was taken to Dambel, where he is venerated as one of the pioneers of the Faith in Africa, and a protector of the parish.