Daniele Comboni

Missionari Comboniani

Area istituzionale

Altri link

Newsletter

In Pace Christi

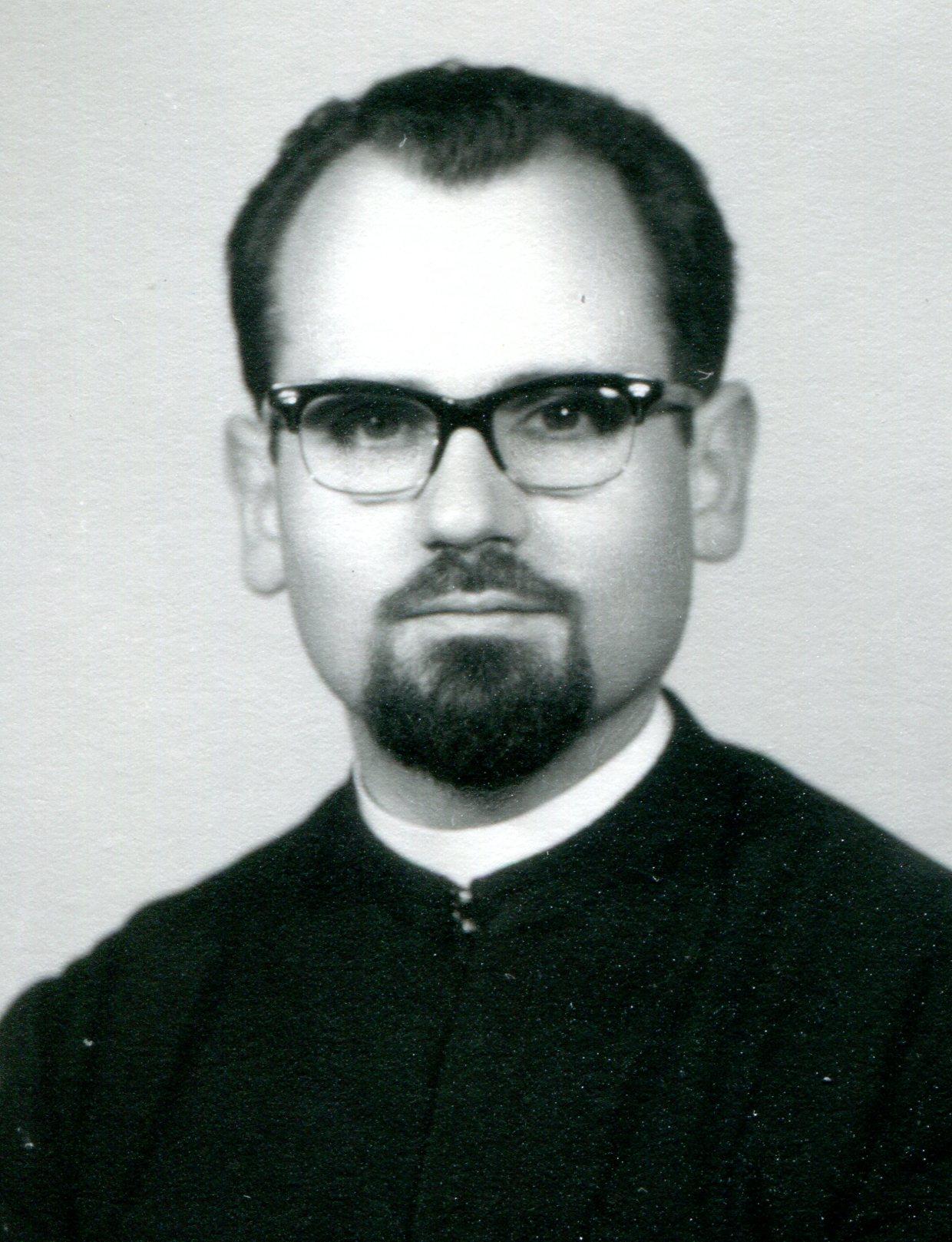

Campdepadrós Aynes Domingo

"Il mio cuore si sta indebolendo sempre più... basta che Tu mi faccia crescere nel tuo amore, voglio solo questo. Amarti sempre più e amare i fratelli e le sorelle... In questo momento non ho paura di morire, ma quando non riesco a respirare, ho paura di soffrire... Sia fatta la Tua volontà. Fammi paziente, compassionevole, un buon servo, e abbi pietà di me."

P. Domingo scrisse queste frasi alla fine del suo ultimo ritiro, il 30 luglio 1993. La grave afflizione cardiaca si era acuita con tutta la sua severità, e sapeva che la morte, probabilmente repentina, poteva venire a qualsiasi momento. Da allora visse con la convinzione, e anche con la gioia, che ogni giorno era un dono di Dio.

Infatti, visse ancora per quasi due anni, ma con l'attività severamente ridotta, e alternando tra periodi in casa e ricoveri nell'ospedale. Nel febbraio del 1995 fu ricoverato per l'ultima volta, e messo in lista per un trapianto. Passò un mese abbondante prima che si trovasse un cuore adatto (4 aprile); ma le condizioni generali del padre erano troppo precarie, e morì l'11 aprile. I medici confessarono che non avevano mai avuto un paziente come P. Domingo: allegro, paziente, servizievole, capace di dare coraggio e speranza agli altri malati e al personale sanitario. Fino alla fine dimostrò due caratteristiche essenziali: una forte personalità e una profonda fede sulla quale si basava la sua allegria.

Infanzia e vocazione

Domingo nacque in Barcelona il 26 settembre 1934, figlio di Luis e di Francisca. Era il secondo di otto figli, due dei quali morirono in infanzia. Quando terminò la scuola primaria, all'età di 12 anni, cominciò a lavorare come falegname, professione che esercitò fino alla sua entrata nel seminario a 21 anni.

Durante questo lungo periodo era attivo nell'apostolato parrocchiale e nella Gioventù Cattolica Operaia (JOC). Era il periodo della dittatura del generale Franco. A 17 anni, il suo impegno per la giustizia portò Domingo a partecipare a una manifestazione contro il regime. Fu arrestato e passò 40 giorni in carcere. Molti anni dopo nel 1981, quando chiese il visto per andare negli Stati Uniti, apparve la "fedina sporca", e dovette inoltrare domanda per far cancellare i suoi antecedenti penali ("oltraggio al Capo di Stato").

Il periodo in prigione fu decisivo per far emergere con sempre più chiarezza la sua vocazione al sacerdozio, che sentiva come una chiamata a "portare la giustizia ai poveri". A 21 anni entrò nel seminario minore di Barcelona. Era molto più vecchio dei compagni, che subito presero a chiamarlo "nonno". Era già in filosofia nel 1960 quando P. Enrico Faré passò per il seminario. Domingo aveva pensato più di una volta alla possibilità di farsi missionario. La visita di P. Faré lo convinse totalmente, e gli indicò anche la strada: sarebbe diventato missionario comboniano.

Però qui iniziò una battaglia inaspettata: il rettore e il direttore spirituale del seminario, senza opporre la sua vocazione sacerdotale e missionaria, si mostrarono sommamente restii all'idea che si facesse religioso. "Per entrare in una congregazione - dichiarò il direttore spirituale - bisogna avere la vocazione religiosa, ma tu hai la vocazione sacerdotale!" Fu un cercare il capello nell'uovo seccante per Domingo: a 25 anni, gli pareva di essere trattato come un bambino sciocco. Senza nessuna ragione evidente, gli offrivano sì la possibilità di essere missionario - ma come sacerdote diocesano!

Durante i mesi di maggio e giugno 1960 mantenne una fitta corrispondenza con P. Faré. La chiarezza di idee di questo e la maturità stessa di Domingo sciolsero la situazione. "Ogni vocazione - scrisse con logica ferrea P. Faré - richiede due cose: la retta intenzione e l'idoneità. Se il tuo direttore spirituale avesse dei dubbi seri riguardo a questi punti, dovresti ascoltarlo con docilità... Ma se, come dici, hai già il suo consenso riguardo al primo punto, riconoscerà poi che hai i doti per essere missionario in Africa. E questo è tutto per te."

Alla fine, i formatori nel seminario diedero il loro consenso, e Domingo entrò nel noviziato comboniano di Gozzano (Novara) nell'agosto dello stesso anno.

Sacerdozio e prima destinazione missionaria

Trascorso il noviziato, proseguì con gli studi teologici a Venegono. Durante questo periodo soffriva spesso di mal di testa, così che non poteva dedicarsi allo studio come avrebbe voluto, e fu costretto, con grande rammarico, a fare eccezioni al ritmo della vita comunitaria, per dormire un po' di più. Si chiamava "lazzarone", ma non lo era affatto: ciò che fu costretto a perdere dello studio lo ricuperò con interesse nel lavoro materiale, esercitando la sua esperienza di falegname e i grandi doti pratici nelle riparazioni alla casa dello scolasticato di Venegono.

Fu ordinato sacerdote a Moncada il 29 giugno 1967. Dopo un breve periodo di animazione missionaria in Spagna, partì per la prima destinazione missionaria in Ecuador il 19 febbraio 1968. Durante i cinque anni della sua permanenza nella missione il suo lavoro rimase sempre lo stesso: insegnante e direttore spirituale nella Scuola del Sacro Cuore a Esmeraldas. Avrebbe preferito il lavoro pastorale, ma allo stesso tempo si sentì felice perché, tra l'altro, si trovava "in un posto che nessuno mi invidia!".

Domingo svolse una grande attività tra i giovani, e i frutti sono rimasti. Oltre alle lezioni di religione - fino a 30 ore la settimana - e la direzione spirituale di molti giovani, era assistente del gruppo di Scouts, del NAIM e del Movimento della Famiglia Cristiana...

Nel 1971 gli si propose un ritorno alla provincia d'origine. Tirava in Spagna il vento della nazionalizzazione rapida, che la Direzione Generale accolse con simpatia. Pensavano a Domingo per qualche posizione di responsabilità. Reagì con forza, quasi con durezza. "In Spagna - scrisse al Provinciale, P. Faré - sarei un uomo amareggiato, un uomo finito alla mia età. Qui ho tutto il lavoro che desidero... Se, nonostante questo, i superiori mi comandano, non avrò altra alternativa che obbedire - ma con TERRORE."

Non era semplicemente una reazione naturale davanti alla prospettiva di lasciare la missione: sapeva che sarebbe arrivato in un ambiente teso per la questione della nazionalizzazione della provincia, che alcuni patrocinavano con vigore, ma che egli stesso considerava troppo precipitata. Domingo accennò anche a qualcosa che fece notare più di una volta durante la sua vita: il proprio senso delle sue limitazioni. "Guardi - scrisse nella stessa lettera - che non è una sciocca umiltà, ma pura realtà; so di avere molti limiti, e non mi faccio illusioni di nessun tipo."

Provinciale in Spagna

Di fronte a questa reazione, la sua rotazione fu rimandata fino a febbraio 1974. Al suo arrivo in Spagna fu destinato alla comunità di Barcellona come formatore dei postulanti fratelli. Al Capitolo del 1975, pur non essendo delegato, fu chiamato per i lavori preparatori, e fu uno dei segretari del Capitolo.

Nel febbraio del 1976 fu eletto provinciale, succedendo nella carica al suo antico reclutatore, P. Faré, il primo superiore della provincia. La nomina fu firmata da due Superiori Generali: P. Agostoni per i FSCI e P. Klose per i MFSC, perché in Spagna era iniziata dal 1975 l'esperienza della riunione, che si estese a tutto l'Istituto soltanto nel 1979.

Il periodo che gli toccò vivere come provinciale non era dei più tranquilli. Le acque erano ancora mosse dal tema della "nazionalizzazione della provincia", e si era nel tempo degli "sperimenti" e delle defezioni di sacerdoti e religiosi - alle quali i comboniani spagnoli fecero il loro contributo. Domingo dovette tenere un equilibrio difficile tra la tolleranza e ciò che riteneva fossero le esigenze di un progetto comune. Era abitualmente gioviale, amichevole, vicino; ma sapeva anche essere diretto e tagliente. Ovviamente, non sempre secondo il gusto di tutti.

La salute non lo aiutava molto. Una mattina, due mesi dopo ch'era entrato in carica, lo trovarono svenuto nella sua camera. I medici non trovarono niente di grave, salvo una tendenza all'ipertensione: aggravata, a loro giudizio, dalle pressioni psicologiche, e consigliarono un posto di minore responsabilità. Proprio all'inizio del suo provincialato! Era il momento di mostrare il lato robusto del suo carattere. Domingo continuò nel suo incarico, e lo fece con giovialità e con stile. Nel 1978 fu rieletto con il suffragio di ben 47 dei 53 votanti.

Formatore di teologi

Nessuno avrebbe aspettato che Domingo, a 47 anni e senza sapere una parola di inglese, sarebbe stato assegnato allo scolasticato di Chicago. Ma così fu. "Rida, rida di gusto!" scrisse a P. Faré. "Sto ridendo anch'io, e abbandonandomi nelle mani del Signore, confidando che Egli, che mi ha assistito in questi sei anni di provincialato, continui ad aiutarmi nel mio futuro di formatore."

Non è, dunque, dal carattere forte che trae la forza per accettare la nuova destinazione con tanto stile; ma dalla sua confidenza in Dio, rafforzata dalla preghiera. Domingo è, infatti, un uomo di preghiera assidua. Il giorno del suo svenimento in camera i confratelli si sono accorti che qualcosa non andava perché non l'hanno visto in cappella di mattino presto, come solito. Uno scolasticato da Chicago lo ricordava così: "Si vedeva in cappella alle 05.00, anche quando si era coricato alle due. Talvolta il sonno lo vinceva; il breviario cominciava a scivolargli di mano ed egli si svegliava di colpo per afferrarlo prima che cadesse per terra."

Date le circostanze, il lavoro nello scolasticato si prospettava molto duro. L'ignoranza dell'inglese lo mise in una posizione di inferiorità, e in un mondo - quello dell'America - molto diverso dal suo, per cui non sapeva quali parametri applicare. "I ragazzi mi hanno già schedato come `spiritualista' - scrisse durante il primo mese - e in qualche modo hanno ragione perché, senza dubbio, parlo molto della preghiera. Ma la mia vita non è coerente come dovrebbe essere, a livello di servizio, di carità fraterna, ecc. Ho l'impressione che il Signore intenda purificarmi molto."

Secondo i punti di riferimento prevalenti allora a Chicago, Domingo era certamente uno spiritualista, in quanto il suo linguaggio teologico non seguiva la linea "sociale" che era in auge; ma non nel senso che non si interessava della realtà concreta intorno a lui, o che non era impegnato con essa. Il giovane di 17 anni che si era ribellato contro le falsità e le ingiustizie del regime franchista è ancora vivo e vegeto in lui. Vuole che gli scolastici escano per l'apostolato, e scoprano la povertà nella società americana; e si lamenta che l'immagine dell'America che esiste all'estero è soltanto quella del dollaro.

Domingo non era un teologo, né dato alla speculazione. Ma non stonava per questo nel teologato. Aveva una personalità troppo ricca, con troppi valori da offrire, per permettere agli scolastici di cadere nella tentazione di sottovalutarlo in confronto con i luminari della teologia al CTU. Era proprio la persona da aiutarli a contrapporre alle belle teorie sentite in classe la realtà concreta di ogni giorno.

In questo rispetto è eloquente la descrizione che fa di lui uno scolastico: "La prima volta che vidi P. Domingo lo presi per un operaio che stava facendo delle riparazioni per la casa. Era estate; alcuni scolastici erano in cucina, tenendo in mano bicchieroni di acqua con cubetti di ghiaccio. In quel momento entrò lui, i cappelli bianchi di polvere, le mani sporche, la camicia bagnata di sudore. Il suo stile di formazione aveva queste caratteristiche: realismo e piedi per terra. Domingo interpretava i suoi criteri formativi con le proprie sofferenze nella vita e quelle che vedeva nella vita della gente della parrocchia di San Vito. Povertà, abusi di ogni tipo, gente sull'orlo del precipizio umano e spirituale...; di fronte a questo, i problemi e le posizioni ideologiche nello scolasticato sembravano una perdita di tempo, un lusso borghese. Per lui, la capacità di pagare di persona era l'unico argomento convincente".

Una parrocchia e... l'ultimo saluto

Durante il suo tempo di formatore nello scolasticato, Domingo assunse anche altri impegni. Dal 1984 al 1986 era membro del Consiglio Provinciale della NAP. Fu rieletto nel 1992, ma dopo un anno si ritirò per motivi di salute. Lavorò anche come assistente nella parrocchia di San Vito nel quartiere Pilsen. Il suo campo preferito, nel quale diventò un vero esperto, era quello dei matrimoni: passava delle ore in paziente ascolto di una coppia, per poi consigliarla con una sicura chiarezza. Domingo aveva una intuizione speciale, come un sesto senso, per scoprire la causa profonda di un problema, che gli interessati o non volevano o non potevano esprimere. E' stato consultore del tribunale diocesano nei casi di nullità.

Alla fine del 1990 completò il servizio di formatore. Quando nel febbraio del 1991 i comboniani presero la responsabilità per le parrocchie di San Donato e dei Sette Santi Fondatori nella periferia di Chicago, P. Domingo fu nominato superiore della comunità e coordinatore dell'équipe pastorale, e rimase in carica fino alla morte. La parrocchia di S. Donato era formata prevalentemente di immigrati di lingua spagnola, e quella dei Sette Fondatori di neri. Il pesante compito di Domingo e degli altre era di formare una comunità di valori umani e spirituali da una popolazione che aveva in comune soltanto il fatto di vivere nello stesso quartiere.

Nel 1993 fu costretto a dimezzare le attività, per l'aggravamento dell'afflizione cardio-polmonare di cui soffriva da vari anni. Ma rimase nella breccia, spingendosi al limite delle sue forze. Nel febbraio del 1995 fu ricoverato all'ospedale per l'ultima volta, ma anche dal suo letto, attaccato a tubi e fili innumerabili, si intratteneva pazientemente con i fedeli che venivano a trovarlo, o che chiedevano per telefono il suo consiglio. La fine la sappiamo.

Secondo P. Saoncella, superiore della comunità comboniana vicina all'ospedale Loyola dove è morto, il ritornello dell'inno della vita di Domingo potrebbe suonare così: "Sono preparato per la vita e per la morte, e sono contento e grato."

(P. Juan Núñez)

Da Mccj Bulletin n. 189, ottobre 1995, pp.62-67

******

"My heart is getting weaker and weaker... as long as you make me grow in your love, this is what I want. To love you ever more and to love and serve you in my brothers and sisters... At this moment I am not afraid to die, but when I cannot breathe, I am afraid of suffering... Your will done. Make me patient, compassionate, a good servant, and have pity on me."

Fr Domingo wrote these words at the end of his last retreat on 30th July 1993. His serious heart condition was about to become critical, and he knew that he could die suddenly and unexpectedly. From then on he lived each day with the conviction - and with the joy - that it was a gift from God.

In fact, he lived almost two more years, though with all his activities drastically reduced, and his time divided between home and hospital. In February 1995 he entered hospital for the last time, and was put on the waiting list for a transplant. It was more than a month before a suitable heart was found (4th April); but Fr Domingo's general condition was too weak, and he died on 11th April.

The medical staff confessed they had never had a patient like Fr Domingo: cheerful, patient, helpful, able to give courage and hope other patients and the staff alike. Right to the end he displayed two essential characteristics: a strong personality and a deep faith on which his happiness was based.

Early years and vocation

Domingo was born in Barcelona on 26th September 1934, the son of Luis and Francisca. He was the second of eight children, two of whom died in infancy. At the end of primary school, at the age of 12, he started work as a carpenter and continued in this trade until he entered the seminary at 21.

During this long period he was active in the parish and in the Young Catholic Workers (JOC). It was the time of the Franco dictatorship. At 17, his commitment to justice caused Domingo to take part in a demonstration against the regime, for which he was arrested and spent 40 days in prison. Years later, in 1981, when he applied for a visa to enter the United States, his crime showed up, and he had to apply to have his penal record ("outrage to the head of State") cancelled.

The time in prison made his priestly vocation much clearer: he felt it as a call to "bring justice to the poor". He entered the junior seminary of Barcelona at 21, much older than his companions, who quickly started calling him "granddad!". While he was in Philosophy in 1960, Fr Enrico Faré visited the seminary. Domingo had thought about being a missionary; the visit confirmed both the decision and the direction: he would be a Comboni Missionary.

But an unexpected struggle then began: the rector and the spiritual director of the seminary, while not denying his priestly and missionary vocation, objected strongly to his becoming a religious. "To enter a congregation," asserted his spiritual director, "one must have a religious vocation, and you have a priestly vocation!" It was hair-splitting that annoyed Domingo; at 25, he felt he was being treated like a stupid child. For no apparent reason, he was being offered the chance to be a missionary - but as a secular priest.

During the months of May and June 1960 a lot of letters passed between him and Fr Faré. The clear ideas of the latter and Domingo's own maturity led to a solution. "Each vocation," wrote Fr Faré with inescapable logic, "requires two qualities: right intention and aptitude. If your spiritual director has serious doubts about these two points, you should listen to him obediently... If, as you say, you already have his agreement on the first point, he will see you have the qualities to be a missionary in Africa. And that is all you need."

In the end, the formators in the seminary gave their consent, and Domingo entered the Comboni Novitiate at Gozzano (Novara, Italy) in the August of the same year.

Priesthood and first mission assignment

After the Novitiate, he continued his studies for the priesthood in Venegono. He suffered frequent headaches during this time, which prevented him from studying as he wanted, and made him, much to his regret, miss part of the rhythm of community life, to sleep a bit longer. He called himself a "lazy-bones", though he was nothing of the sort: what he lost in study he made up with interest in material work, using his experience as a carpenter and his practical gifts to make repairs to the scholasticate.

He was ordained priest in Moncada on 29th June 1967. Following a short period of missionary animation in Spain, he left for his first mission assignment in Ecuador on 19th February 1968. During his five years there he had just the one job: teacher and spiritual director in the Sacred Heart School in Esmeraldas. He would have preferred parish work, but he was happy because, among other things, he was in "a post that nobody envies me!"

Domingo did great work among the youth, and the fruits still remain. Besides his religion classes - up to 30 periods a week - and the spiritual guidance of many young people, he was religious assistant of the Scouts, the NAIM and the Christian Family Movement...

In 1971 a return to his home Province was proposed. There was a thrust towards rapid nationalisation in the Spain, favoured by the General Administration. It was thought Domingo could take on some responsible post. He reacted strongly. "In Spain," he wrote to the then Provincial, Fr Faré, "I would be embittered, a man at the end of his days. Here I have all the work I want... If, in spite of this, the superiors order me, I will have no alternative but to obey - but with TERROR!"

It was not just a natural reaction at the prospect of leaving the mission: he knew he would arrive in Spain to a tense atmosphere over the question of the nationalisation of the Province, which some pushed with vigour, but which he considered too hasty. Domingo also mentioned something to which he returned more than once throughout his life: his awareness of his limitations. "Note," he wrote in the same letter, "that this is not stupid humility, but pure reality; I know I have many limitations, and I have no illusions of any sort."

Provincial of Spain

In the face of this reaction, his rotation was put off until February 1974. When he arrived in Spain he was assigned to the Barcelona community as formator of the postulant Brothers. At the 1975 Chapter, though not a delegate, he was called for the preparatory work, and was one of the secretaries of the Chapter.

In February 1976 he was elected Provincial, succeeding Fr Faré, the first provincial in Spain and his "recruiter". His nomination was signed by two Superiors General: Fr Agostoni for the FSCJ and Fr Klose for the MFSC, since it was in the Province of Spain that the first experience of reunion began in 1975. This was extended to the whole Institute only in 1979.

His period as Provincial was not the most peaceful. The waters were still troubled by the theme of the "nationalisation of the Province", and it was a time of "experiences", with defections among priests and religious - to which the Spanish Comboni Missionaries contributed their share. Domingo had to walk a tightrope between tolerance and what he considered to be the demands of a common project. He was habitually pleasant, friendly and attentive, but also knew how to be direct and cutting. Obviously, not to everyone's taste.

His health did not help too much. One morning, two months after he entered office, he was found unconscious in his room. The doctors found nothing serious besides a tendency to high blood pressure aggravated, they judged, by psychological pressures; and they advised a less responsible position. Right at the start of his mandate as Provincial! It was time to show the robust side of his character. Domingo soldiered on, and he did it with kindness and style. In 1978 he was re-elected, with 47 of the 53 votes.

Formator of Theologians

Nobody would have expected Domingo, at 47 and knowing no English, to be appointed to the Scholasticate of Chicago. But so it was. "Laugh! have a good laugh!" he teased Fr Faré. "I'm laughing too, and putting myself in the Lord's hands, trusting that He, who assisted me throughout the last six years as Provincial, will continue to do so during my future as formator."

So it is not from his strong character that he draws the strength so stylishly to take on the new appointment; it is from his trust in God, strengthened in prayer. Because Domingo is a man of assiduous prayer. The day he collapsed in his room in Madrid, his confreres knew something was wrong when they did not see him in the chapel early on, as was his custom. A scholastic from Chicago remembers: "In the morning he could be seen in the chapel at 05.00, even though he had gone to bed at two. Sometimes sleep overcame him; his breviary would begin to slip from his hand, and he would wake with a start just in time to stop it falling."

The task in the scholasticate promised, in the circumstances, to be tough. Not knowing any English put him in a position of inferiority, and in a world - that of America - a lot different from his own, so that he did not know what parameters to apply. "The lads have already classified me as a `spiritualist'," he wrote in the first month, "and in some way they are right, because maybe I talk a lot about prayer - in fact, I do. But my life is not as consistent as it should be, at the level of service, brotherly love, etc. I have the impression that the Lord wants to purify me a lot."

By the terms of reference that then applied in Chicago, Domingo was certainly a spiritualist in that his theological language did not align with the "social" line that was in favour there; but not in the sense that he was not interested in the concrete reality around him, or was not involved in it. The youth of 17 who rebelled against the falsehood and injustice of the Franco regime was still very much alive in him. He wanted the scholastics to go out on apostolate and discover the poverty of American society, and he complained that the image of America that existed abroad was only that of dollars.

Domingo was not a theologian, nor given to speculation. But he was not out of place in a theologate. He had too rich a personality, with too many values to offer, to let the scholastics fall into the temptation of underestimating him against the luminaries of theology at the CTU. He was the man to help them compare the pretty theories heard in class with the concrete situation of every day.

In this respect, the description of him by a scholastic is eloquent: "The first time I met Fr Domingo I mistook him for a workman doing repairs in the house. It was Summer; some scholastics were in the kitchen holding big glasses of water with ice cubes. Just then he came in, his hair white with dust, his hands filthy and the sweat soaking his shirt. His first greeting was. His formation style had this characteristic: realism and feet on the ground. Domingo interpreted his formation criteria through his own sufferings in life and those he saw in the people of St Vitus parish. Poverty, all kinds of abuse, people on the edge of the human and spiritual precipice...; in the face of this, ideological problems and positions inside the scholasticate seemed a waste of time, a bourgeois luxury. To put oneself on the line was the only convincing argument for him."

A parish and... the final step

While he was formator in the scholasticate, Domingo undertook other tasks. From 1984-86 he was a member of the Provincial Council of the NAP. He was elected again in 1992, but resigned a year later because of his health. He also worked as assistant in St Vitus Parish in the Pilsen quarter. His preferred field, in which he was a real specialist, was that of marriages: he would spend hours listening patiently to couples, and then counselled them with clear certainty. Domingo had a special intuition, like a sixth sense, to discover the deep cause of the problem, that those concerned could not, or would not, express. He was a consultor of the diocesan marriage tribunal in annulment cases.

At the end of 1990 he finished his term as formator. In February 1991, when the Comboni Missionaries took on the pastoral care of the parishes of St Donatus and the Seven Holy Founders on the outskirts of Chicago, Fr Domingo was named superior of the community and coordinator of the pastoral team, a post he held until his death. St Donatus was made up mainly of Hispanic immigrants, and the Seven Founders by black people. The task of Domingo and the others was to build a community of human and spiritual values from a lot of people who had only one thing in common: they lived together in the same slum.

In 1993 he had to cut his activities by half, because of the aggravation of the heart and lung trouble he had had for several years. But he stayed in the breach, pushing himself to the limits of his powers. In February 1995 he entered hospital and did not leave again, but even from his bed, connected to wires and monitors, he dealt patiently with the many parishioners who visited him, or who phoned asking for his advice. We know about the end.

According to Fr Saoncella, superior of the Comboni community near Loyola Hospital, where Domingo died, the chorus of the hymn of his life could be: "I am ready for life and for death, happy and grateful".