Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

Tuesday, November 6, 2018

« Since it has an enormous impact on the daily life of all of us, finance cannot be included in the “darkest corners”; however, it is certainly one of the topics least willingly spoken of and around which, at times, there hovers an unreasonable reticence. The RL, in its desire to incarnate a great reality in the complexity of real life, dedicates to it the fifth and last chapter entitled “The Administration of the Goods of the Institute” (n. 162-175). (…) The choice of renouncing all material goods for an ideal and to live the poverty of freedom echoes the words of Comboni: “to suffer for Jesus and gain souls for him is the greatest resource of the true missionary’s heart” (W 5446).» Fr. Claudio Lurati, General Bursar.

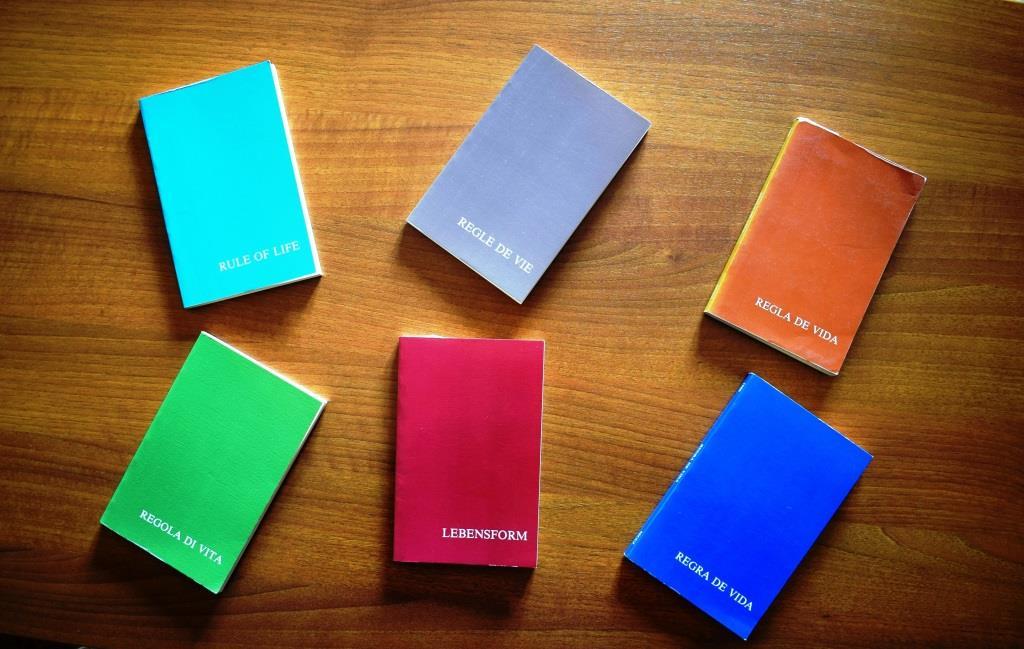

“TO BE FREE…”

POVERTY AND THE CHARISMATIC MANAGEMENT OF

MATERIAL GOODS IN THE RULE OF LIFE

Nos. 162-175

It is nice to think that in this phase of its history our Institute is involved in a process of revisiting and revising the Rule of Life (RL), like the woman who “lights the lamp and sweeps the house” to find her lost coin (cf. Lk 15,8), to reclaim her most precious possession and reconstitute the integrity of her patrimony: to do this, the woman in the Gospel is prepared to turn her house upside down, move the furniture and search the darkest corners.

Since it has an enormous impact on the daily life of all of us, finance cannot be included in the “darkest corners”; however, it is certainly one of the topics least willingly spoken of and around which, at times, there hovers an unreasonable reticence. The RL, in its desire to incarnate a great reality in the complexity of real life, dedicates to it the fifth and last chapter entitled “The Administration of the Goods of the Institute” (n. 162-175).

The vow of poverty is described in the RL in Nos. 27-32 and is outlined as a series of limiting conditions that the missionary accepts in view of a great ideal: “to be free to bring the message of the Gospel to the poorest and most abandoned and to live in solidarity with them” (n. 27).

The value-structure developed in these five paragraphs needs concrete realisation and we find this in Part Five of the RL where the administrative dynamics of the Institute takes shape, seeking to remain faithful to the principles set out on Nos. 27-32.

The last part of the article brings to light some areas where the RL may be in greater need of revision. This concerns the integration of a structure that is already, broadly speaking, in line with the recent interventions of the Magisterium and the demands of the modern world.

1. The guiding principle in being “poor in the sequela of Christ”

Wanting to make a synthesis and a schematic arrangement, I believe I may say that the “Fifth Part” of the RL realises three fundamental principles that are based upon the description of the evangelical counsel of poverty (Nos. 27-32. These are:

a) Collegiality: no one takes decisions alone

b) Mission: everything is for one purpose

c) Transparency: everyone gives an account of everything

a) Collegiality (“Communitarian poverty” – n. 29): no one decides alone but always in communion with the competent body whether this is the community, the province or an administrative Council and so on.

For this reason the RL describes the decision-making process, the competence of each one and their limits. In current language, the Total Common Fund (TCF) is our closest approximation to the principle of collegiality. In the RL, of course, there is no mention of the TCF which is a term adopted only afterwards. However, the ideal structure is entirely present.

The General Directory for Finance describes the TCF as “the financial instrument that concretises community planning” and «pursues provincial objectives that are the result of common discernment (CA ’03 n. 102)». By means of the TCF we wish to reach ever greater levels of sharing and fraternity, transparency and equity, the sense of belonging and responsibility” (GDF 4).

b) Mission (“The use of material goods” – n. 30): all the goods have a common purpose which is evangelisation. The charismatic quality of management can be measured by their actual use for their fundamental purpose.

The term “whatever” referring to goods acquired or donated reaffirms the radical nature of this option. Use for the fundamental purpose also includes the preparation and livelihood of the missionaries: consider how much the Institute invests in the formation of candidates and in language studies. The directorial paragraphs integrate the charismatic vision with the preferential option for the poor and the choice of poor means. This urgency imposes a simple style of life marked by “sharing and self-limitation of goods” (n. 164).

We again find traces of this charismatic concern in n. 167. It is a basic attention that must be exercised because “the offerings of the people of God and from the work of the missionaries” make up the main sources of income of the Institute (n. 167), as is still the case today.

c) Transparency (“Vow of poverty” – n. 31): it is often described as that which allows those outside the house to see what is happening inside it. The TCF is a process of transparency: It means looking at each other's house, hoping that with time the houses will become one. Concretely, everyone must give an account of everything and this is achieved by a system of budgets, reports and checks.

Number 31 is rather complex. The first three sub-paragraphs of the directorial part define the application of Canon Law 668, indicating the stages and ways of permanent choices concerning the personal patrimony of the confrere. The vow of poverty does not imply renouncing the radical ownership of previously possessed goods or goods inherited from relative (RL 32).

Paragraphs 4-8, instead, clearly state that in daily or apostolic life there is no room for “mine” or private property and that everything (literally “everything”) must be accounted for.

In my view, the duty of giving an account, even though it is affirmed, lacks the necessary visibility and is placed only in the margins of the text as a sub-number in a directorial paragraph (n. 31.5).

In revising the RL, we must take into account the contemporary juridical sensibility which stresses that the failure to give an account is a grave omission both by those failing to do so and those whose duty it is to insist on it but do not sanction eventual omissions.

2. The application of principles in the administrative structure of the Institute

In order for the principles I have just described to be respected, we need a suitable structure that protects and promotes them and in which each of the members acts according to his competence for the wellbeing of the whole body.

a) First of all we have the function of government where financial decisions take shape and are consolidated.

Number 165 tells us that “they pertain to the superiors and their councils at various levels” and must be preceded by “consultation with the respective secretaries for finance”.

The faculty of decision is not unlimited. In the first place there are some decisions for which the “deliberative” vote of the council is expressly required: e.g. the approval of budgets and the balance sheets, and permission to exceed the limits of extraordinary administration (cf. n. 127.2 and n. 139.6).

If the decision concerns an intervention of an extraordinary nature that exceeds the limits established by the General Chapter, “permission to exceed these limits may be given by the Superior General with the consent of his Council, after having obtained, in writing, the views of the General Economate” (n. 170). It is sometimes necessary to obtain the permission of the Holy See (170.1). This principle is based upon CIC 635 which affirms that the goods of a religious Institute are “ecclesiastical”, meaning that, in the final analysis, they belong to the universal Church for the pursuance of its purposes and that the good of the Church takes precedence.

In the concrete life of a community or of a province, the majority of financial decisions are contained in an important document universally called the “budget”. It follows planning and represents its translation in financial terms.

This is why the process of elaborating the planning/budget is strategic in the life of a community/province and requires that it be given the necessary care and attention.

The RL mentions the budgets (Nos. 163.5, 164.2, 172.2) but does not elaborate much as to their function. In recent years, due to the practice of the TCF, awareness of the role of the budget has greatly increased and it may, perhaps, be given space in the RL. The budgets as well as the balance sheets, also have a fundamental function in the evaluation of an activity and in overseeing “life-style”.

b) Consultative and executive role: the RL requires both the provinces and the General Administration to have a secretary for finance (n. 172-173).

In all organisations, the decision-making and executive roles are clearly distinct. The same applies to religious Institutes as laid down in CIC 636. The RL repeats the concept in Nos. 172.5, 173.1 e 174.1.

In practice, the two basic levels of expression of an organisation are:

Government: it has the duty to decide, direct and control.

Management: it has the function of providing technical expertise, carry out decisions and guarantee accurate reports of activities.

At the General level, the RL requires that consultation take place both with the General Economate and the Council for Finance. The latter is an organ that has its parallels in the provinces and guarantees ample representation of the different components of the Institute. To it the RL assigns the duty of “auditing the budgets and the financial reports; examining financial programmes and verifying the administrative procedures and organisation of the General Economate and studying the basic problems in the financial sector of the Institute” (n. 172.2).

c) To complete the picture we have the normative and controlling apparatus. Naturally, the RL cannot go into the details of financial choices: it offers general principles but takes for granted the “General Directory of Finance” (GDF - RL n. 175), elaborated and updated under the authority of the General Council.

The Directory exists and is reviewed every six years before the General Chapter. It contains “further principles” and other “norms”. Its periodical revision allows the Institute to keep pace with the rapid changes that take place in the financial world and to be ready for the continual development required by the mission.

Regarding financial investments, for instance, the RL affirms that they are a “supplementary income” (RL 167.1) and entrusts the task of regulating them to the General Directory for Finance in which there is actually an entire chapter dedicated to the topic (GDF n. 33).

The system of control aims at controlling and verifying the proper use of goods according to their assigned purpose and to protect the good name of the Church and of the Institute, avoiding any threat to the light of the charism and its service in the world.

La Rule of Life requires responsibility and the sharing of information (RL 166) and also indicates some preventive methods of control:

- distinction of roles: superior/bursar (RL 173.1)

- the deliberative vote of the Council for the approval of the budget and balance sheets (cf. n. 127.2 and n. 139.6)

- limits of ordinary financial administration (RL 170).

Other aspects of the apparatus of control have been subsequently developed by the Code of Conduct and by the General and Provincial Directories such as, for example, the obligation to have joint accounts.

Later controls are substantially entrusted to the examination of the budgets. The Provincial Council has the duty to examine them, make appropriate comments and approve them.

The RL also requires that “the economate at the higher level provides technical assistance to the lower one and examines its books” (n. 163.4).

At this point we observe something that is practically impossible to achieve: each year the General Economate “reviews” the accounts of the provinces but this service is not the “examination of the books” which would require actually examining them in loco. The question is further complicated by the English translation which uses the word “audit”, a more complex matter than simply “examining the books”.

In recent general Chapters, there has been a change of direction towards the option for an external review of the administration, this time using the correct translation “audit”. The General or Provincial Council exercises its duty of control of management through the annual revision carried out by external consultants who are asked to verify:

- the accuracy of the report;

- its agreement with bank statements;

- agreement between budgets and expenditure;

- authorisation for financial transactions (budgets, the decision of the Financial Council within the limits of the Directory);

- availability of receipts and other supporting documents;

- conformity with civil law.

3. Which sections of the RL would need to be revisited?

Some areas in need of change have already been pointed out and here we only mention them again. Others are mentioned for the first time.

a) Budgets and Balance Sheets. The Total Common Fund, the joy and sorrow of Comboni news in recent years, ought to be given its own place in the text, even if it does not seem to me to be necessary to use the term “Total Common Fund” which, with the passing of years, may seem out-dated.

The principle of sharing in planning and resources is clearly affirmed (n. 162 e 164). What must mostly be illustrated are the two essential implications: budgets and balance sheets. The text speaks of sharing and planning: less evident is the fact that, without budgets and balance sheets being discussed and approved in community, the yearning for sharing remains just a dream.

b) Transparency and controls. As stated above, the duty of giving an account is central but it has a very low profile in the text (31.5).

It is certainly necessary to re-order the review of reports in n. 163.

In general, the whole question of checks and controls is always more decisive both regarding the confreres responsible and the lay people entrusted with this task. When a responsibility is delegated, we must make sure that the remit of each person is defined and a system of controls set in place. The system of checks is a great challenge for the future; any carelessness in this field proves very costly. There are objective responsibilities for which the excuses “I didn’t know” or “I didn’t understand” do not constitute sufficient justification.

Still in this context, it is useful never to forget the recommendation that comes from the RL to follow both ecclesiastical as well as civil law in the administration of goods (Nos. 45.1 and 169; cf. CIC 22).

c) Dividing our Inheritance. While we understand the reasons behind each article, we have to reconcile the apparent contradiction between the affirmation of the “single collective patrimony” (n. 163) and that of the “division of the patrimony” (n. 168). Properties and responsibilities are very distinct from one province to another, even in the context of a very loud call for solidarity.

d) Recent Magisterium. Last March, the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life (CIVCSVA) published the document Finance at the Service of the charism and the mission.

The result of work lasting four years, it concerns “orientations”, aimed at providing guidance on the management of economic resources by integrating existing rules and the Code of Canon law.

Even though it always needs to be renewed, the main recommendations of the document agree that our RL and our practice broadly provide for:

- Preparing the annual balance sheets

- the Directory

- Secretariats

- Immovable patrimony

- Limits for extraordinary administration

Other recommendations will have to be taken into account:

- Limit on the term of office of the bursar

- Separation of the roles of the bursar and the legal representative

The document speaks much of valuing the patrimony of religious Institutes in line with the priorities of their charisms and the mission that derives from them. It also dwells upon responsible collaboration with the laity. But these themes would require deeper reflection beyond the scope of this article.

Conclusion: the pearl of great price

To conclude this reflection, I wish to turn again to a very welcome invitation extended to us by the above-mentioned document which in turn paraphrases a Gospel parable: “Let us witness by our life that we have found the pearl of great price” (Finance…, n. 98).

The choice of renouncing all material goods for an ideal and to live the poverty of freedom echoes the words of Comboni: “to suffer for Jesus and gain souls for him is the greatest resource of the true missionary’s heart” (W 5446).

Fr. Claudio Lurati

General Bursar