Daniel Comboni

Comboni Missionaries

Institutional area

Other links

Newsletter

The worst insult that one could direct to a Jew was “dog” or “pagan”; the second was “samaritan,” that amounted to “bastard, renegade, heretic!” (Jn 8:48). At the end of his book, Ben Sira reports an almost sarcastic saying which shows the contempt of the Jews against the Samaritans. He calls them: “the foolish people who live in Shechem” and that does not even deserve to be considered a people (Sir 50:25-26).

“Who is my neighbour?”

Luke 10:25–37

This Sunday’s Gospel passage (Luke 10:25–37) recounts the parable of the so-called Good Samaritan. A doctor of the Law asks Jesus what he must do to inherit eternal life. Jesus invites him to answer the question himself, and the scribe gives a perfect summary of the Law: to love God and one’s neighbour. But when he then asks, “Who is my neighbour?”, Jesus replies with a parable.

A man, travelling from Jerusalem to Jericho, is attacked by robbers. The 27 km journey, with a drop of around a thousand metres (from Jerusalem at +750m to Jericho at -250m), was extremely dangerous as it passed through the rugged and arid wilderness of Judea – ideal for ambushes. For that reason, people usually travelled in caravans.

In the parable, Jesus presents the attitudes of three individuals towards the wounded man: a priest, a Levite, and a Samaritan. The priest and the Levite, both linked to Temple worship, see him and pass by on the other side. At this point, the listeners might have expected a third, “lay” character, with a hint of subtle anticlerical criticism – a critique that perhaps neither they nor we today would have objected to.

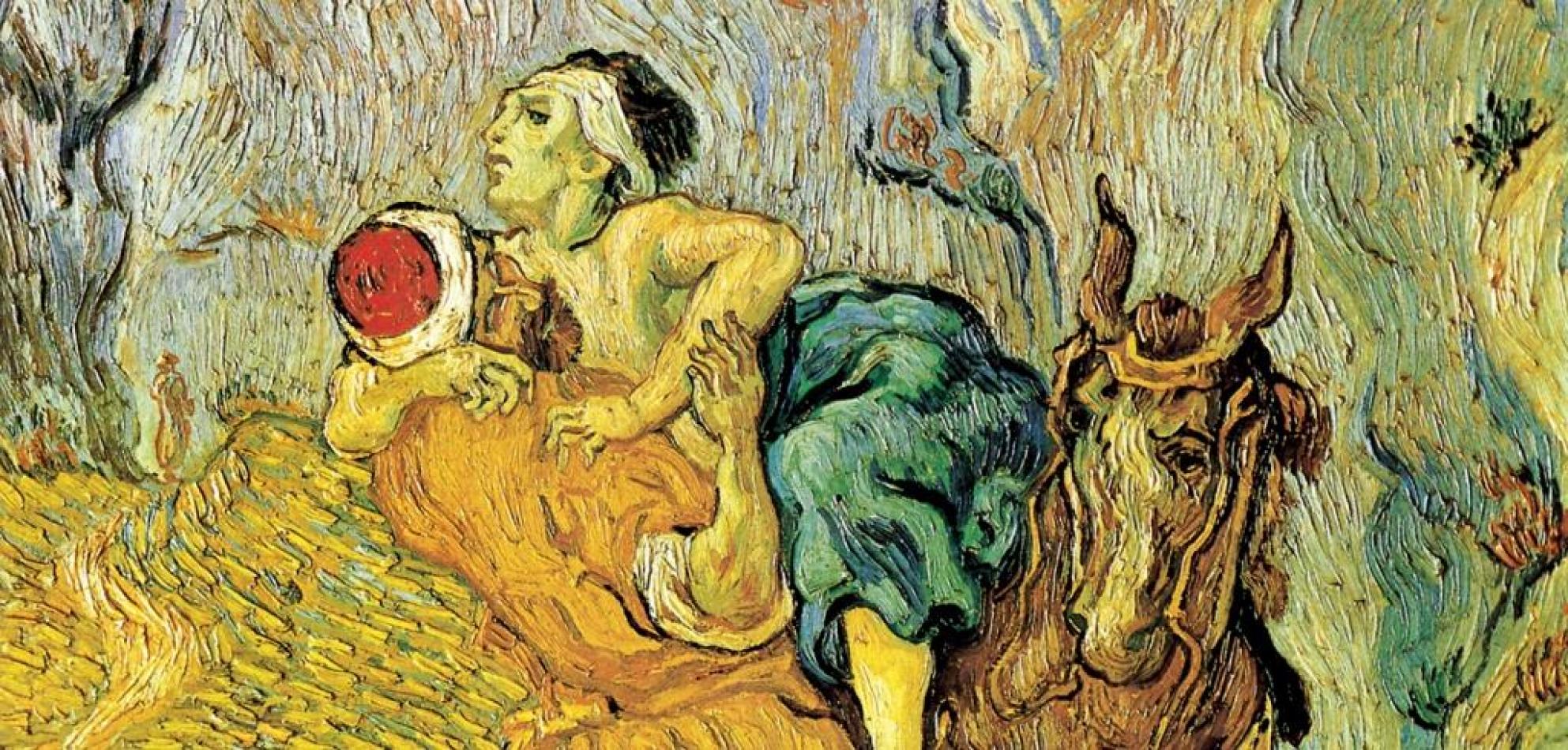

But Jesus introduces a Samaritan – a heretic, a foreigner, an enemy. Everyone is waiting to see what he will do. And what happens? The Samaritan, “on seeing him, was moved with compassion”. At this moment, I imagine everyone would have been stunned. The parable takes a prophetic turn, exposing empty and formal religiosity. Today, we might see ourselves reflected in the priest and the Levite: the “believers”, the practising. While the Samaritan represents those who, without appealing to God or His Law, act with generosity and altruism. In this sense, the parable deeply challenges us.

“What is written in the Law? How do you read it?”

The first reading (Deuteronomy 30:10–14), chosen to correspond with the Gospel, and the responsorial psalm (Psalm 19), speak of law, commands, precepts and statutes. They use verbs such as: to command, obey, observe, carry out... Concepts we struggle with today. Even though we understand that laws are necessary for social coexistence, we find it hard to accept limitations on our freedom. And when we discover that God’s Word governs even our relationship with Him, it can make us uneasy. With what sincerity have we repeated with the psalmist: “The precepts of the Lord rejoice the heart”?

We should then reflect on the counter-question Jesus poses to the doctor of the Law: “What is written in the Law? How do you read it?”. As if to say it’s not enough to know what’s written – one must also reflect on how that Word is understood. The “how do you read it?” is addressed to us, too. We must approach Scripture with the intention of moving from “what is written” to “how I understand and live it”.

It’s interesting to note that the first reading, the psalm, and the Gospel engage all of the human faculties: heart, soul, mind, eyes, hands... “You shall return to the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul”; “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength and with all your mind, and your neighbour as yourself”. If all of these dimensions are not involved, reading Scripture remains abstract, theoretical, partial, or even distorted.

Closeness and distance

The parable is born from the scribe’s question: “And who is my neighbour?”. It was a debated issue at the time. At best, a neighbour was only a fellow Jew who was practising. Jesus changes the perspective: to the question “Who is my neighbour?”, he effectively responds: “Don’t ask who deserves your love; be the one who becomes a neighbour to those in need”.

A key theme this Sunday is the concept of closeness. In the first reading we read: “This word is very near to you, it is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you may carry it out”. The true sign that the Word is close is compassion, which makes us capable of approaching those in need, as the Samaritan does: “He came near him, saw him, and was moved with compassion”. And he drew close! This closeness is translated into concrete gestures: “He bandaged his wounds, pouring oil and wine on them; then he placed him on his own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him”.

The Samaritan “was moved with compassion”. The verb used by Luke is splanchnizomai, which means to be deeply moved, “to feel it in the guts”. In Luke’s Gospel it appears only three times: when Jesus is moved before the widow of Nain (7:13), in our passage (10:33), and in the parable of the merciful father (15:20). In all three instances, compassion expresses itself in drawing near and touching. To be moved is a verb especially attributed to God. It’s no accident that the scribe doesn’t use this verb to describe the Samaritan, but instead the expression “show mercy”.

The conclusion of the parable is clear and direct: “Go and do likewise!” Become a neighbour. Show mercy. And you will become a son or daughter of the God of Compassion – like Jesus, the true “Good Samaritan”.

For personal reflection

“And now the truth emerges: there are people considered impure, not orthodox in faith, despised, who know how to ‘show mercy’, who know how to practise intelligent love for their neighbour. They do not appeal to the Law of God, to their faith, or to their tradition, but simply, as human beings, they know how to see and recognise the other in need and put themselves at the service of their wellbeing, care for them, and do what good is needed. This is mercy! In contrast, there are religious men and women who know the Law well and are zealous in observing it meticulously, who – precisely because they focus more on what is “written”, what is handed down, rather than on life itself, on what’s happening to them and on who is in front of them – fail to observe the true intention behind God giving the Law: which is love for others! But how can this be? How can it be that religious people, who go to church daily, pray and read the Bible, not only fail to do good, but even refuse to greet their brothers and sisters – something even pagans do? This is the mystery of iniquity at work within the Christian community itself! We shouldn’t be shocked, but we must examine ourselves, asking whether, at times, we too fall into the camp of those hardened ‘righteous’ ones – those legalists and pious people who do not see their neighbour but believe they see God; who do not love the brother they see but are convinced they love the God they do not see (cf. 1 John 4:20); those zealous activists for whom belonging to the community or the Church is a guarantee that blinds them, making them incapable of seeing the other in need.”

(Enzo Bianchi)

Fr. Manuel João Pereira Correia, mccj

To inherit Life

Gospel reflection – Luke 10: 25-37

Introduction

To love God would not make sense for the ancient Greeks. The gods could love people: they show their preference by giving special gifts and favors. As a sign of gratitude, they expected sacrifices and burnt offerings from the person they have shown favor. A reflection of this mentality is also present in some texts of the Old Testament. Through the mouth of prophet Malachi, the Lord complains of the despicable holocausts that priests offer him: “The servant respects his master … Where is the honor due to me?” (Mal 1:6). Unlike the pagan peoples, Israel loves her God. Here’s what Moses recommends to the people: “What is it that the Lord asks of you if not to love him and serve him with all your heart and with all your soul?” (Dt 10:12). “Love consists in keeping the commandments” (Ex 20:6) and “to follow his ways” (Dt 19:9).

Love of neighbor, above all the poor, orphan, widow, and stranger, is viewed in this frame: This is practiced because it is a work pleasing to God.

The New Testament gives us the full light, one that allows us to understand what it really means to love God. The first letter of John is very explicit: “This is love: not that we loved God but that he first loved us … . Dear friends, if such has been the love of God, we, too, must love one another” (1 Jn 4:10-11).

The logical leap is immediately obvious. We would expect, if God so loved us, we also ought to love him. But God does not ask anything for himself. There is only one way to respond to his love: love your brethren and not “only with words and with our lips, but in truth and in deed” (1 Jn 3:18).

Gospel: Luke 10:25-37

The worst insult that one could direct to a Jew was “dog” or “pagan”; the second was “samaritan,” that amounted to “bastard, renegade, heretic!” (Jn 8:48). At the end of his book, Ben Sira reports an almost sarcastic saying which shows the contempt of the Jews against the Samaritans. He calls them: “the foolish people who live in Shechem” and that does not even deserve to be considered a people (Sir 50:25-26).

Actually, the Jews had their own good reasons for believing that the Samaritans were of the “excommunicated.” For many centuries they were so mixed up with other people that they cannot now be considered descendants of Abraham. They were contaminated with pagan cults, had forgotten the traditions of their fathers and lived impurely (2 K 17). They did not accept the books of the prophets, nor those of wisdom nor the Psalms as sacred. Even Jesus, responding to the Samaritan woman, does not hesitate to tell her: you do not even know which god you worship, for salvation comes from the Jews (Jn 4:22). Two Sundays ago, the Gospel recalled the snub made to the Master and the apostles by the Samaritans (Lk 9:53).

Today’s Gospel begins (vv. 25-29) presenting to us not a Samaritan, but a Jew, not a sinner, but a righteous man, a teacher of the law who asks Jesus: “What shall I do to inherit eternal life?” Note the fine theology: he does not speak of “merit,” but to inherit eternal life. The inheritance—we know it—is not earned; one receives it completely free of charge.

Adapting himself to the practice of rabbinic disputes, Jesus does not give an immediate answer, but addresses him a counter-question: “What is written in the law?”

The rabbi promptly appeals to two biblical texts. The first is well known because every pious Israelite recites it in the morning and evening prayers: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength” (Dt 6:5); the second, on which he insisted a little less, is taken from the book of Leviticus: “and your neighbor as yourself” (Lev 19:18). Perfect answer!

Is that all then? If God’s judgment is about the knowledge of a doctrine, the lawyer should be given full marks. But Jesus, after the praise—“What a good answer!”—adds, “Do this and you shall live” (v. 28). “Do!” It’s not enough to “know.” It is life that proves if we have assimilated or not the Word of the Lord.

The rabbi—who failed to embarrass Jesus—insists: “And who is my neighbor?” He is also willing to do, but without overdoing it. He wants to establish well the boundaries of love. There was a discussion among the rabbis about who should be considered neighbor. Some—referring to the aforementioned text of Leviticus that parallels the term neighbor with sons of your people—said they had to love only the children of Abraham. Others extended this love also to foreigners who lived long in the land of Israel. But all agreed in saying that the distant peoples and, above all, the enemies were not neighbors. The monks of Qumran adhered to this principle: “love the children of the light and hate the children of darkness” and for the “children of light” they meant the members of their community.

Jesus does not answer the question of the doctor of the law, because he considers it outdated. For him there is no barrier between peoples and the problem is not knowing how far love should reach, but how to demonstrate it by loving God and the brothers and sisters.

It is on this point—the most important, indeed, the only one that matters—that the Jew and the Samaritan are compared. The assessment is not given on the basis of what one knows, says, the faith one professes by mouth, but in what one does.

“There was a man going down from Jerusalem to Jericho” … (v. 30).

These two towns are located 27 km from each other. The road is a sharp descent (a drop of 1000 meters), through the Judean desert along the wadi Quelt. It continues among cliffs, caves, and precipices to the plains of Jericho, the beautiful “City of Palms.” There Herod, the wealthy families of the capital, and many priests of the temple had their villas and winter residences. This road was always traveled in a convoy to avoid being attacked by robbers and bandits.

A man—Jesus says—who knows well the danger of the place—was attacked by robbers who beat him, robbed him and left him half dead along the way.

Who was he? We do not know anything about him: neither age nor profession, nor the tribe to which he belonged, nor the religion he professed. We do not know if he was white or black, good or bad, friend or foe. What did he do in Jerusalem: to pray or to revel? To offer sacrifices in the temple or to steal? He was qualified in the most generic way: he was a man! And this is enough. Even if he were a wicked person, he would not lose his dignity as a man in need of help.

By chance, a priest and a Levite descended on the same route (vv. 31-32).

That ‘by chance’ is nice! We need not go to look for the needy brother. The circumstances and coincidences make us encounter him. How do churchmen behave?

The Levites were the sexton, the temple guards. We are faced with two Jews, respectable people, people who prayed and had clear ideas about God and religion. Why does Jesus introduce these two “men of the church” in his story? He could have avoided the controversy and shown immediately a positive example. Why provoke the “notables,” the “members of the hierarchy?”

The Master had a little “bad habit” of blaming “religious” persons (cf. Lk 7:44 -47, 11:37-53; 17:18; 18:9-14; etc.). The reason is the same for which, before him, the prophets had strongly attacked the worship, rituals, and the solemn ceremonies of the temple: God does not tolerate exterior formalism used as a convenient loophole to avoid being caught up in the problems of people.

Incense, chants, endless prayers with which one tries to replace the concrete commitment in favor of the orphan, the widow, the oppressed are repugnant to God (Is 1:11-17). Jesus mentions several times the phrase of the prophet Hosea: “What I want is mercy, not sacrifice” (Mt 9:13; 12:7).

What are the priest and the Levite doing? They arrive on the site, they see … but they pass on by the other side. Perhaps they themselves are afraid of being attacked, perhaps they are worried of ritual purity (he could be dead and a dead body prevents one to officiate in the temple), perhaps they do not want to get into trouble or get headaches, perhaps they have no time to lose.

They come from Jerusalem where they have some part in the solemn liturgies. They spent a week—this was the duration of their service—with the Lord and from one who unites oneself to God we would expect love and care for the needy. The two “church people” come from the temple, yet they are insensitive, do not feel compassion—the first of God’s feelings (Ex 34:6). This means that the religion they practice is hypocritical and hardened their heart rather than soften it. What will God do with this religion that provides an alibi to escape the problems of people, which helps to avoid problems by passing “across the street?” The man attacked by bandits is for Jesus the symbol of all the victims of physical and psychological violence.

At this point, the listeners expect that after the two “churchmen” the helper will enter the scene. They are certain that he would be a secular Jew. Had Jesus carried on the parable in this way, the people—who even then showed that benevolent anti-clericalism which also animates today’s Christians—would have recognized and applauded. Instead here’s the surprise. The provocation appears to be one of those that says “the candles’ smoke bothers him”—a Samaritan. Mind you: he is not a “good Samaritan”—as many Bibles say—but just a Samaritan. He was traveling and he had his plans.

The description of what he does at the sight of the wounded man is accurate.

Jesus does not neglect any detail because he wants to contrast his conduct to that of the priest and the Levite. “He came upon the man, he was moved with compassion. He went over to him, and cleaned his wounds with oil and wine, and wrapped them in bandages. Then he put him on his own mount and brought him to an inn, where he took care of him” (vv. 33-34).

In the face of a person who is in need, he no longer follows the head, but the heart. He forgets his business commitments, religious norms, fatigue, hunger, and fear. He immediately acts, committing himself to the complete solution of the case. He is not pushed to act by religious reasons, by the desire to please God, by the calculation of merits to gain heaven by helping the poor, but only by compassion, the fact that he feels pity squeezing his heart. He is moved by the feeling that—while not being aware—it is the projection of what God feels.

Like what Nathan did when he told David the parable of the sheep, Jesus does not give his judgment on the incident. He wants the lawyer to be the one to do so. For this, he poses a question that reverses the one that has been given at the beginning. “Who is my neighbor?”—he was asked. Now he asks: “Which of these three, do you think made himself neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?” (v. 36). The problem—as we have already mentioned above—is not to determine how far one stretches the boundaries of the term “neighbor,” but: who becomes neighbor, who draws near, who is capable of loving, who shows to have assimilated the merciful conduct of God.

The doctor of the law responds: “The one who had mercy on him” (v. 37). He avoids—for obvious reasons—to say the name “Samaritan,” but is forced to admit that he is the model of one who knows how to make oneself neighbor.

The last words of Jesus to the lawyer summarize the message of the whole parable: “Then go and do the same!” (v. 37). Make yourself a neighbor to the one in need and inherit life.

The parable has an explosive message: who loves his neighbor certainly also loves God (cf. 1 Jn 4:7). He may turn him down in words but in reality, he is not rejecting God; perhaps he only rejects his false image. The “Samaritans” who love the brother and sister in need, perhaps without knowing it, are worshiping the true God.